BAIL OUT

Though critically damaged, the right wing remained

intact as the giant bomber started its approach to

the base. The plane was at 10,000 feet when flight

commander Tulloch engaged the landing flaps.

The B–52G’s landing flaps have only two

positions — full up and full down. When the flaps

moved to full down the damaged wing ruptured

and sheared off, and the pilots lost all control of the

aircraft. Maj. Tulloch immediately ordered the crew

to eject.

Standard equipment for the bomber includes six

seats equipped with escape hatches and ejection

systems. The plane is designed to enable four crew

to eject from the upward-firing top hatches and two

from the belly hatches below, clearing them from the

plane before their parachutes automatically opened.

Six of the eight personnel aboard Keep 19 sat in

ejection seats. The other two would have to secure a

parachute, make their way to any open hatch, and

jump free. Upon Maj. Tulloch’s order, all six crew-members

in ejection seats bailed out at 9,000 feet.

A THE FIRST BOMB

As the plane began to disintegrate, the two

Mark 39 nuclear bombs separated from the aircraft.

In the case of an accident, and to avoid a nuclear

disaster, both bombs had a series of arming mech-anisms.

One of those mechanisms was a parachute

that activated when the bomb was released from

the plane. The parachute was required to slow the

bomb’s descent so the aircraft could safely fly out of

the blast zone.

The first bomb fell free with no parachute and

dove at some 700 mph into the ground at C.T. Davis

farm near Nahunta Swamp in rural Wayne County.

It partially broke apart on impact and torpedoed

through the wet earth to a depth of some 50 feet,

leaving a cavernous crater. Even with the intense

shock at impact, none of the conventional explosives

designed to sequentially trigger the nuclear explo-sion

activated.

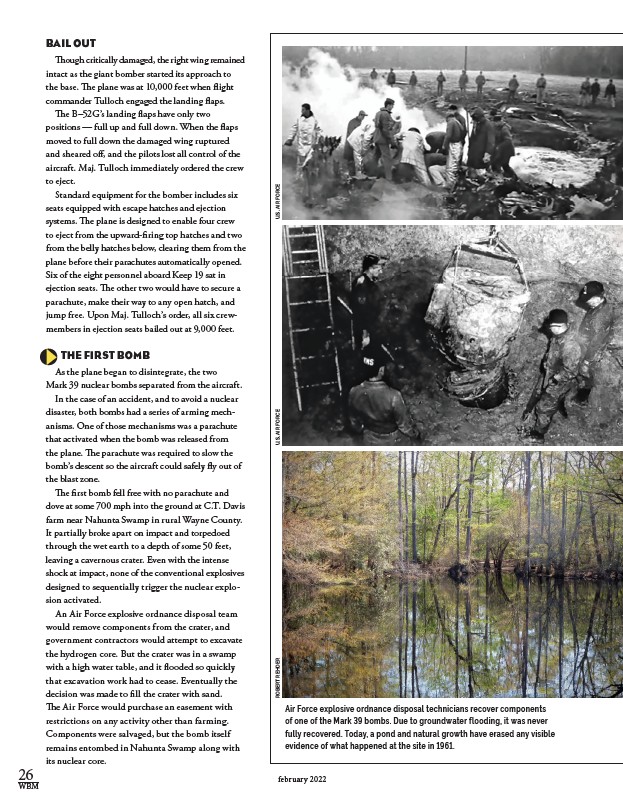

An Air Force explosive ordnance disposal team

would remove components from the crater, and

government contractors would attempt to excavate

the hydrogen core. But the crater was in a swamp

with a high water table, and it flooded so quickly

that excavation work had to cease. Eventually the

decision was made to fill the crater with sand.

The Air Force would purchase an easement with

restrictions on any activity other than farming.

Components were salvaged, but the bomb itself

remains entombed in Nahunta Swamp along with

its nuclear core.

Air Force explosive ordnance disposal technicians recover components

of one of the Mark 39 bombs. Due to groundwater flooding, it was never

fully recovered. Today, a pond and natural growth have erased any visible

evidence of what happened at the site in 1961.

ROBERT REHDER U.S. AIR FORCE U.S. AIR FORCE

26 february 2022

WBM