HE first navigational aid to New Inlet came about because of the second

conflict between the United States and England.

“Everybody knows Fort Fisher was built to protect New Inlet during the

Civil War. But they realized as early as the War of 1812 that there needed to

be some type of defense on the point,” Sawyer says.

T

Troops were sent from Raleigh to strengthen the coastal defenses and build a fort and

battery. The war with England lasted from June 1812 until February 1815. The only

skirmish off the Carolina coast occurred in July 1813, when the British raided Ocracoke

Inlet. The Federal Point cannons weren’t needed to fire on the enemy, but they became a

landmark in peacetime.

“The battery and the barracks were used as a navigation aid to get into New Inlet in 1815

and 1816,” Sawyer says.

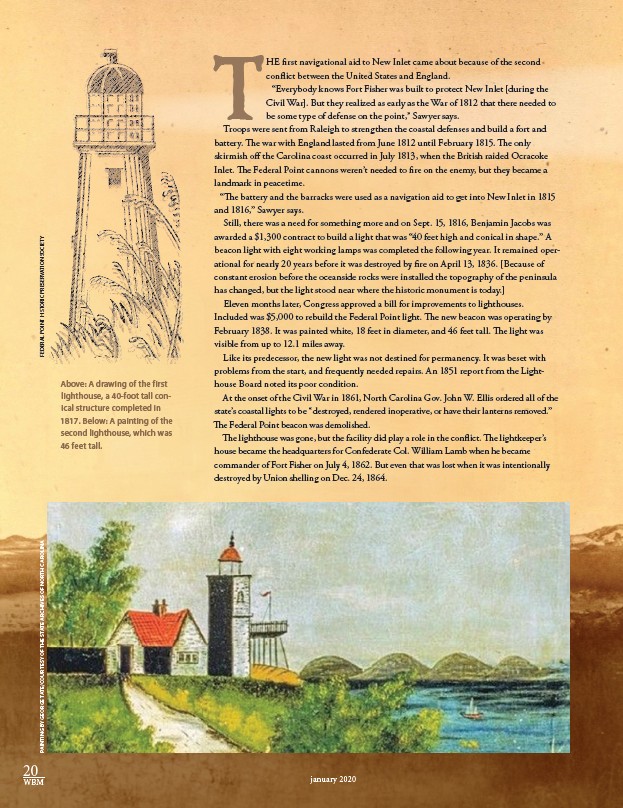

Still, there was a need for something more and on Sept. 15, 1816, Benjamin Jacobs was

awarded a $1,300 contract to build a light that was “40 feet high and conical in shape.” A

beacon light with eight working lamps was completed the following year. It remained oper-ational

for nearly 20 years before it was destroyed by fire on April 13, 1836. Because of

constant erosion before the oceanside rocks were installed the topography of the peninsula

has changed, but the light stood near where the historic monument is today.

Eleven months later, Congress approved a bill for improvements to lighthouses.

Included was $5,000 to rebuild the Federal Point light. The new beacon was operating by

February 1838. It was painted white, 18 feet in diameter, and 46 feet tall. The light was

visible from up to 12.1 miles away.

Like its predecessor, the new light was not destined for permanency. It was beset with

problems from the start, and frequently needed repairs. An 1851 report from the Light-house

Board noted its poor condition.

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, North Carolina Gov. John W. Ellis ordered all of the

state’s coastal lights to be “destroyed, rendered inoperative, or have their lanterns removed.”

The Federal Point beacon was demolished.

The lighthouse was gone, but the facility did play a role in the conflict. The lightkeeper’s

house became the headquarters for Confederate Col. William Lamb when he became

commander of Fort Fisher on July 4, 1862. But even that was lost when it was intentionally

destroyed by Union shelling on Dec. 24, 1864.

Above: A drawing of the first

lighthouse, a 40-foot tall con-ical

structure completed in

1817. Below: A painting of the

second lighthouse, which was

46 feet tall.

PAINTING BY GEORGE TATE/COURTESY OF THE STATE ARCHIVES OF NORTH CAROLINA FEDERAL POINT HISTORIC PRESERVATION SOCIETY

20

WBM january 2020