A BRIEF HISTORY

Salt has shaped our civilization from the very beginning, and its storied

past is inextricably intertwined across cultures. Throughout history it has

been coveted, fought over and hoarded because of its labor-intensive collec-tion

methods and scarce availability.

In the ancient world, regions rich in salt became significant trade centers,

and routes connecting them to other areas were vital. One such route was

the Roman Via Salaria, or Salt Route. In Ancient Rome, salt was so precious

that it made up part of a soldier’s wages.

As civilizations and agriculture spread in the known world, salt became

a traded commodity and trade routes were established between Africa, the

Middle East and Europe because of it. Earning itself the nickname “white

gold” during the Middle Ages, it was as valuable as oil and gas is today.

Salt shortages spurred George Washington to seek independence from

England; and Gandhi started the passive rebellion in the early 1900s in

India because of a salt tax.

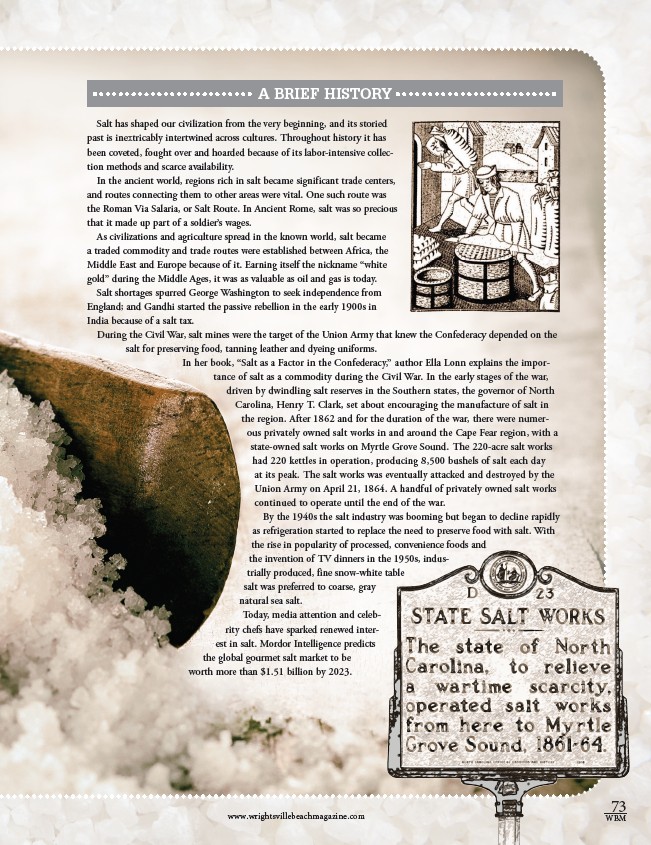

During the Civil War, salt mines were the target of the Union Army that knew the Confederacy depended on the

salt for preserving food, tanning leather and dyeing uniforms.

In her book, “Salt as a Factor in the Confederacy,” author Ella Lonn explains the impor-tance

of salt as a commodity during the Civil War. In the early stages of the war,

driven by dwindling salt reserves in the Southern states, the governor of North

Carolina, Henry T. Clark, set about encouraging the manufacture of salt in

the region. After 1862 and for the duration of the war, there were numer-ous

privately owned salt works in and around the Cape Fear region, with a

state-owned salt works on Myrtle Grove Sound. The 220-acre salt works

had 220 kettles in operation, producing 8,500 bushels of salt each day

at its peak. The salt works was eventually attacked and destroyed by the

Union Army on April 21, 1864. A handful of privately owned salt works

continued to operate until the end of the war.

By the 1940s the salt industry was booming but began to decline rapidly

as refrigeration started to replace the need to preserve food with salt. With

the rise in popularity of processed, convenience foods and

the invention of TV dinners in the 1950s, indus-trially

produced, fine snow-white table

salt was preferred to coarse, gray

natural sea salt.

Today, media attention and celeb-rity

chefs have sparked renewed inter-est

in salt. Mordor Intelligence predicts

the global gourmet salt market to be

worth more than $1.51 billion by 2023.

73

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM