MOTIVATION MAKETH THE MARATHONER

Anna Maltby was never an athlete. A recovering drug addict, the 30-year-old once compared the notion

of running a marathon to “visiting Mars or petting a dinosaur.” Her former addiction, once destructive, now

drives her.

“I honestly don’t think I would still be clean if I hadn’t found something that fuels my soul like running

does,” Maltby says.

Pamela Dieffenbauch runs marathons despite bronchiectasis, a rare lung disease that impairs breathing, but

she runs to set an example for her children.

“I want them to see that they can do hard things, that nothing is out of reach. I want them to understand

that hard work beats talent when talent doesn’t work hard,” Dieffenbauch says.

Peyton Chitty, 50, has a pacemaker to treat a congenital defect that caused his heart to beat too slowly

and even stop. He refuses to allow this to slow him down. Currently ranked among the top 10 cardiac

athletes in the world, he has qualified for the 2019 Boston Marathon.

“Feeling sorry for myself is not an option,” Chitty says. “I choose to control my attitude as that is the

only thing I can control. My condition is a challenge, yes, but I use it to inspire others not to allow them-selves

march 2019

to be overcome by limitations.”

Twenty-eight-year-old Brittany

Copeland Perkins recently ran

a scorching 2-hour, 44-minute

marathon to qualify for the Olympic

Marathon Trials.

These runners are motivated,

and that motivation sparks the fire

of desire to train for hours a day,

day after day, for years, for a life-time.

Nothing compares, they say,

to the sense of accomplishment

they feel upon reaching a marathon

finish line.

GOALS, GOALS, GOALS

Marathoners are highly motivated, goal-oriented overachievers by nature. Rather than discouraging them,

injuries and illnesses drive them to push ever harder toward their goals. Despite her chronic lung condition,

Dieffenbauch, 44, will run the Tokyo Marathon in March. In her bid to qualify for Boston, she must com-plete

a marathon in less than 3 hours and 50 minutes — a pace of 8 minutes, 45 seconds per mile. Boston,

a bucket-list race for many marathoners, has taken on close to a holy significance since being bombed by ter-rorists

in 2013.

Shortly after Maltby began running for her health, her boss upped the ante, surprising her with an entry

into the Quintiles Wrightsville Beach Half Marathon. This sent her on a journey she never thought possible.

“My previous idea of running was huffing and puffing out a mile around the neighborhood before collaps-ing

into a heap at my doorstep,” Maltby says. “But I don’t need a lot of convincing or logic to be talked into

crazy nonsense; I have an addictive personality and I love a challenge.”

After finishing her first half marathon, Maltby turned her attention to the marathon, completing

Wrightsville Beach in 2017 and New York in 2018, where she broke her personal record by 23 minutes. Now

hooked, she plans to run two major international marathons and an ultramarathon in 2019.

Copeland Perkins, who will compete in the Olympic Trials in early 2020, prefers to let her feet do the talking.

“With running, I’ve always been nervous and skeptical to state my goals out loud,” she says. “I have a

personal fear of failure and I worry about what others would think if I didn’t hit my goals. But I’ve recently

found a confidence and mental toughness that have enabled me to push myself in ways I haven’t in years.”

Chitty’s bid to break 1 hour and 30 minutes at the Quintiles Wrightsville Beach Half Marathon will

require he maintain a pace of 6 minutes, 50 seconds per mile, a feat tough even for athletes without

pacemakers.

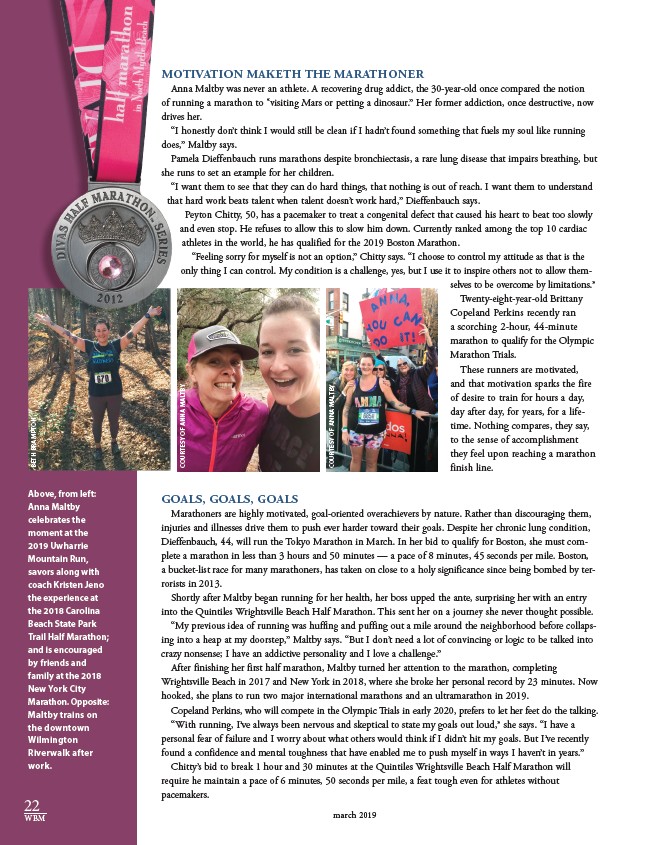

Above, from left:

Anna Maltby

celebrates the

moment at the

2019 Uwharrie

Mountain Run,

savors along with

coach Kristen Jeno

the experience at

the 2018 Carolina

Beach State Park

Trail Half Marathon;

and is encouraged

by friends and

family at the 2018

New York City

Marathon. Opposite:

Maltby trains on

the downtown

Wilmington

Riverwalk after

work.

22

WBM

COURTESY OF ANNA MALTBY

BETH BRAMPTON

COURTESY OF ANNA MALTBY