december 2019

EDWARD’S letters often included tidbits of

leave time experiences and interaction with

locals. Others contained the responses to ques-tions

posed in previous letters by family members, or

responses to news of friends, births, sicknesses, college,

marriages and deaths. In addition to his parents, he

wrote to his siblings, nieces and nephews, always en-couraging

them in whatever endeavor they were occu-pied

in, including younger half-brother John Haywood

Hardin Jr. who had begun attending the University

of North Carolina, the same school that Edward was

“asked to leave” after his first year.

NOV. 25, 1918

From a 10-page letter written to John Haywood Hardin Jr.

I am delighted to know that you have gotten over the

natural homesickness and have settled down to enjoy

college life. It is “kinda” rough on a fellow, those first few

weeks away from home, isn’t it? I can remember as well

as anything how I used to wish I was home again, and think that there never was a more

lonesome sight than that old campus, but one soon learns to love it and actually long to get

back again when away from it.

Good intentions with me are very similar to Boche counterattacks — you can never

tell when they will materialize. I have intended writing you ever since you left for

Chapel Hill but it seems that by the time I’ve written home once or twice a week all

my spare time has been used up… our Division was in the midst of a huge attack

which lasted from September 29th to Oct 20th, and believe me, Buddy, that was

some fight. We first ran the Boche out of the strongest positions they had on the

Western front, in the Hindenburg line, and take it from me, that battle was a

“humdinger.” It lasted from dawn till dark and there was something doing every

minute of the time…

On our Divisional front we had ninety-six machine guns laid for barrage

and a piece of artillery (ranging from 18 pounders to 8 in. Howitzers) for every ten

yards of front. About midnight a runner came around that zero hour would be at 5:50 A.M.

so we went to the Artillery nearest us and synchronized our watches. At 5:45 every gun was loaded, laid

and checked and every gunner standing with his finger on the trigger waiting for the corporal, who had his

eye glued to the watch, to give the signal to “commence firing.” Precisely at 5:50 those thousands of pieces of

artillery and all the machine guns opened up and honestly it sounded as if “all Hell had busted loose.”

At one second before 5:50 there wasn’t a sound except an occasional shell screaming overhead or a burst of

machine gun bullets whizzing past but at one second after 5:50 you couldn’t hear yourself think. Our gun

positions were in a little trench on top of a ridge and from there I could see the whole battle. First it looked

as if the whole world were going up in clouds of mud, dirt, etc. where the shells were hitting. After a three

minute standing barrage the Infantry started the advance under a creeping barrage and it was certainly inter-esting,

and at the same time horrible, to see the dough boys get up from the ground where they had been lying

on their faces, and start forward with the tanks which in the meantime had gone forward under the cover

of the barrage. One could see a squad or a platoon start forward walking as if out for a stroll and suddenly

some fellow would crumple up and lay still or another throw up his hands and fall backwards or still another

stumble and fall with a bullet or piece of shrapnel in his leg and crawl off to a shell hole and squat down

to wait for the stretcher bearers. In the mean time I was having trouble enough of my own … we were in a

trench, with our guns mounted on the parapet and Jerry evidently had this trench taped, for no sooner had

38

WBM

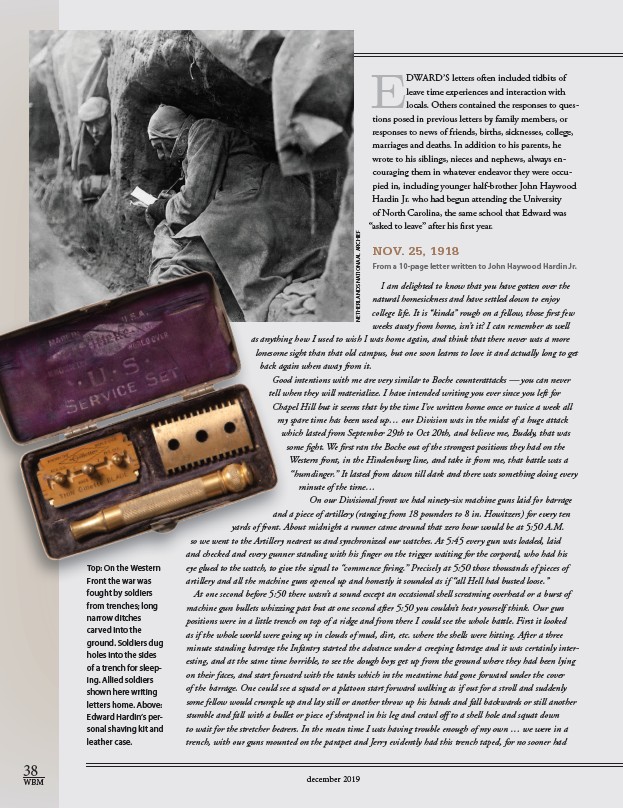

Top: On the Western

Front the war was

fought by soldiers

from trenches; long

narrow ditches

carved into the

ground. Soldiers dug

holes into the sides

of a trench for sleep-ing.

Allied soldiers

shown here writing

letters home. Above:

Edward Hardin’s per-sonal

shaving kit and

leather case.

NETHERLANDS NATIONAAL ARCHIEF