savor — guide to food & dining on the azalea coast

77

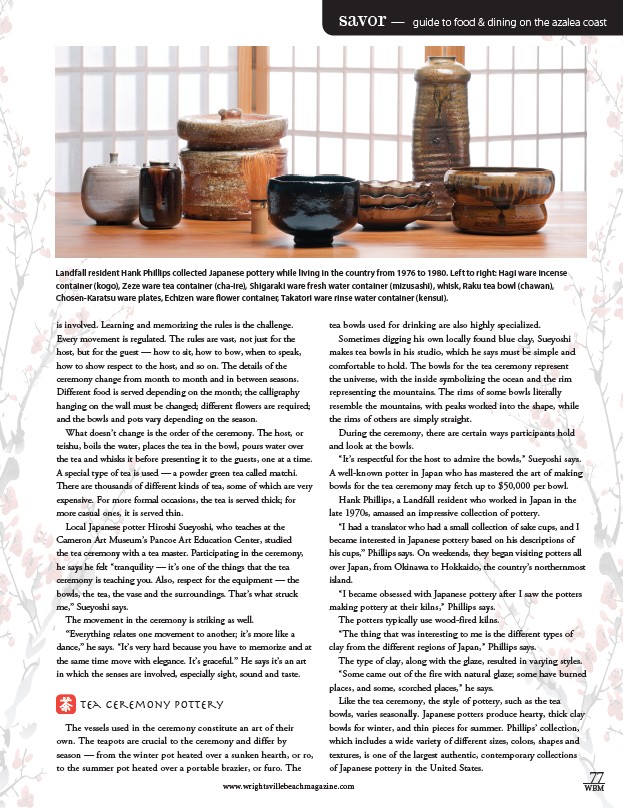

Landfall resident Hank Phillips collected Japanese pottery while living in the country from 1976 to 1980. Left to right: Hagi ware incense

container (kogo), Zeze ware tea container (cha-ire), Shigaraki ware fresh water container (mizusashi), whisk, Raku tea bowl (chawan),

Chosen-Karatsu ware plates, Echizen ware flower container, Takatori ware rinse water container (kensui).

is involved. Learning and memorizing the rules is the challenge.

Every movement is regulated. The rules are vast, not just for the

host, but for the guest — how to sit, how to bow, when to speak,

how to show respect to the host, and so on. The details of the

ceremony change from month to month and in between seasons.

Different food is served depending on the month; the calligraphy

hanging on the wall must be changed; different flowers are required;

and the bowls and pots vary depending on the season.

What doesn’t change is the order of the ceremony. The host, or

teishu, boils the water, places the tea in the bowl, pours water over

the tea and whisks it before presenting it to the guests, one at a time.

A special type of tea is used — a powder green tea called matchi.

There are thousands of different kinds of tea, some of which are very

expensive. For more formal occasions, the tea is served thick; for

more casual ones, it is served thin.

Local Japanese potter Hiroshi Sueyoshi, who teaches at the

Cameron Art Museum’s Pancoe Art Education Center, studied

the tea ceremony with a tea master. Participating in the ceremony,

he says he felt “tranquility — it’s one of the things that the tea

ceremony is teaching you. Also, respect for the equipment — the

bowls, the tea, the vase and the surroundings. That’s what struck

me,” Sueyoshi says.

The movement in the ceremony is striking as well.

“Everything relates one movement to another; it’s more like a

dance,” he says. “It’s very hard because you have to memorize and at

the same time move with elegance. It’s graceful.” He says it’s an art

in which the senses are involved, especially sight, sound and taste.

Tea Ceremony Pottery

The vessels used in the ceremony constitute an art of their

own. The teapots are crucial to the ceremony and differ by

season — from the winter pot heated over a sunken hearth, or ro,

to the summer pot heated over a portable brazier, or furo. The

tea bowls used for drinking are also highly specialized.

Sometimes digging his own locally found blue clay, Sueyoshi

makes tea bowls in his studio, which he says must be simple and

comfortable to hold. The bowls for the tea ceremony represent

the universe, with the inside symbolizing the ocean and the rim

representing the mountains. The rims of some bowls literally

resemble the mountains, with peaks worked into the shape, while

the rims of others are simply straight.

During the ceremony, there are certain ways participants hold

and look at the bowls.

“It’s respectful for the host to admire the bowls,” Sueyoshi says.

A well-known potter in Japan who has mastered the art of making

bowls for the tea ceremony may fetch up to $50,000 per bowl.

Hank Phillips, a Landfall resident who worked in Japan in the

late 1970s, amassed an impressive collection of pottery.

“I had a translator who had a small collection of sake cups, and I

became interested in Japanese pottery based on his descriptions of

his cups,” Phillips says. On weekends, they began visiting potters all

over Japan, from Okinawa to Hokkaido, the country’s northernmost

island.

“I became obsessed with Japanese pottery after I saw the potters

making pottery at their kilns,” Phillips says.

The potters typically use wood-fired kilns.

“The thing that was interesting to me is the different types of

clay from the different regions of Japan,” Phillips says.

The type of clay, along with the glaze, resulted in varying styles.

“Some came out of the fire with natural glaze; some have burned

places, and some, scorched places,” he says.

Like the tea ceremony, the style of pottery, such as the tea

bowls, varies seasonally. Japanese potters produce hearty, thick clay

bowls for winter, and thin pieces for summer. Phillips’ collection,

which includes a wide variety of different sizes, colors, shapes and

textures, is one of the largest authentic, contemporary collections

of Japanese pottery in the United States.

www.wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com WBM