Curtain Call

Tony Rivenbark & the glorious Thalian Hall

BY Dorothy Rankin and Lee Lowrimore

Adapted from a multi-section, two-part series on The History and Construction of Thalian Hall originally published by Wrightsville Beach Magazine in June and July 2010, written by Dorothy Rankin and Lee Lowrimore. Condensed and edited by Pat Bradford.

For 164 years Thalian Hall has been the cultural center of Wilmington. Her story is the Port City’s story. So many marvelous players have performed on her stage for so many generations that it’s easy to overlook the fact that the Hall itself, the very building, the grande dame of the city, tells her own fascinating tale of the times. For our current generation, the Hall’s history has inextricably been interwoven with that of the late Tony Rivenbark, who died at the age of 74 on July 19, 2022.

Arriving for an audition as an 18-year-old, he simply never left. The actor, producer, artist and historian was the executive director of Thalian Hall Center for the Performing Arts for 42 years.

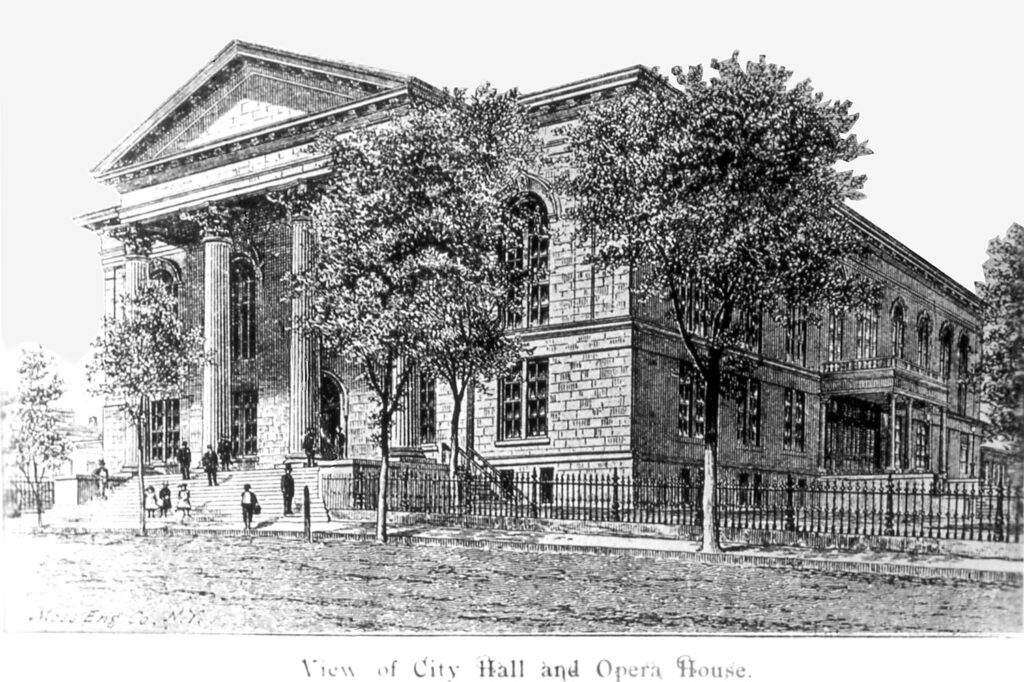

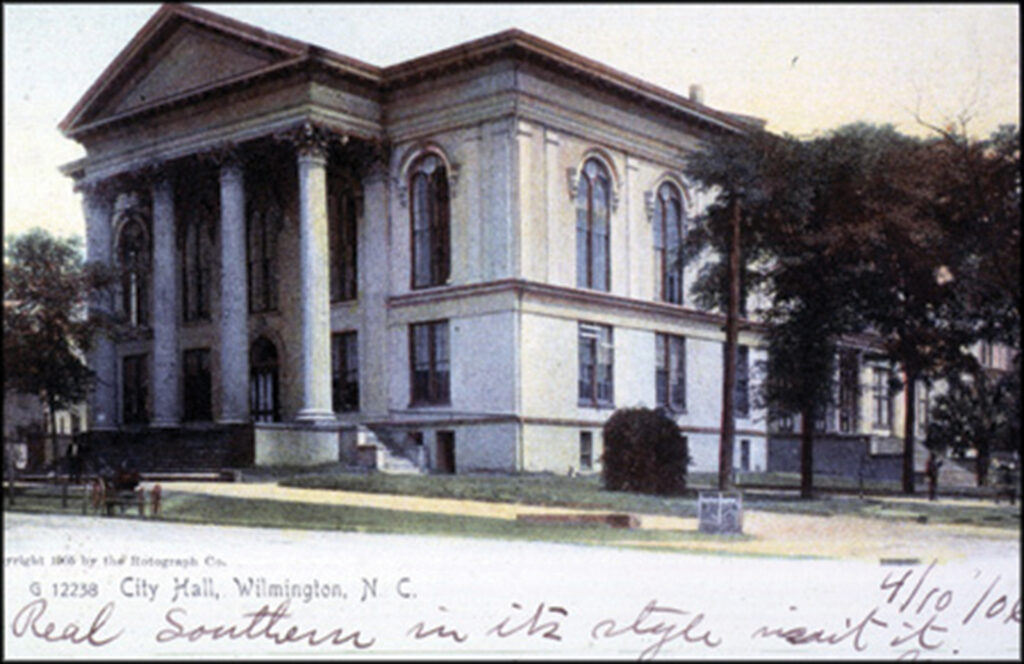

The imposing structure at Third and Chestnut is a two-story, five bay, stucco over brick building with a combination of Classical Revival and late Victorian design elements. The Third Street front facade features a Corinthian four-columned portico.

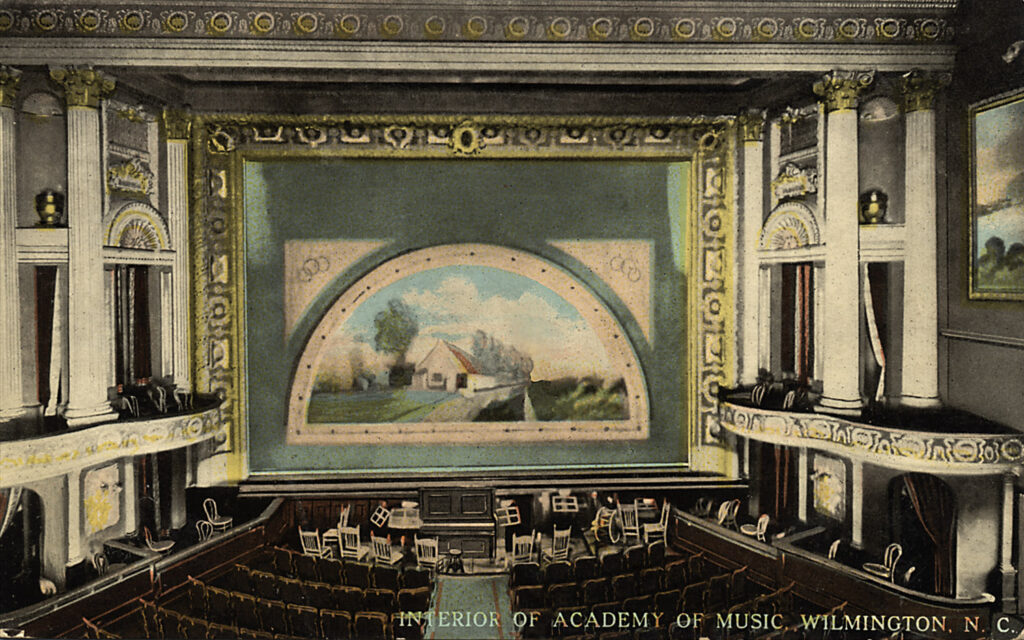

It has gone by different names — The Wilmington Theater, Academy of Music, the Opera House — but it became known as Thalian Hall, or simply “the Hall.”

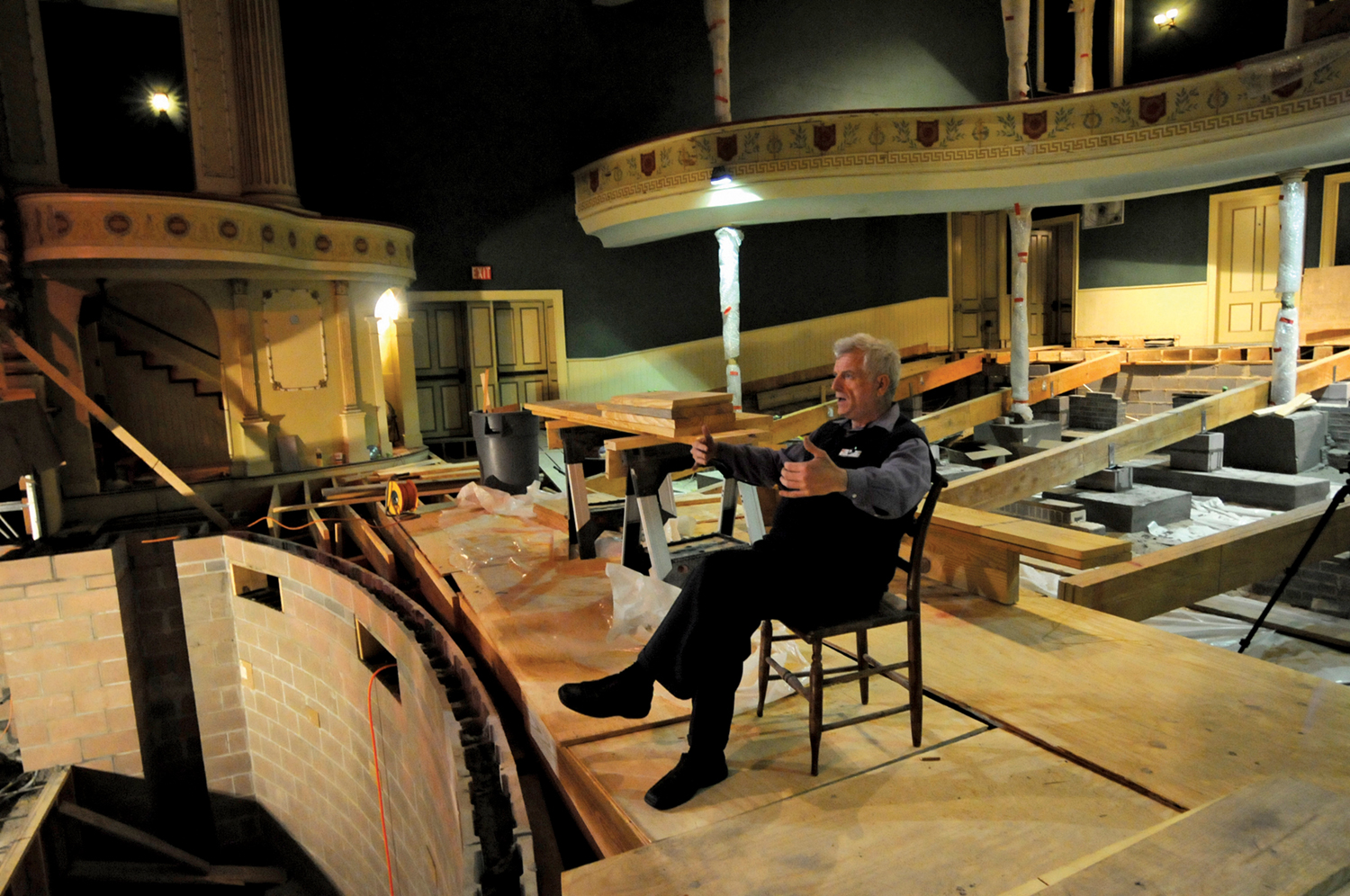

Tony Rivenbark sits at the head of a table set on Thalian’s main stage for Wrightsville Beach Magazine’s The State of the Stage Dinner, part of the Let’s Talk series, in 2007. WBM file photo.

Physically, it’s difficult to overestimate its importance in the city’s downtown.

The building was constructed on a rise above the Cape Fear River. Tony Rivenbark described it in 2010 as like “an Acropolis over the city.” In a town of one- and two-story buildings, he observed, “It had to be phenomenal to the community to watch this building being constructed.”

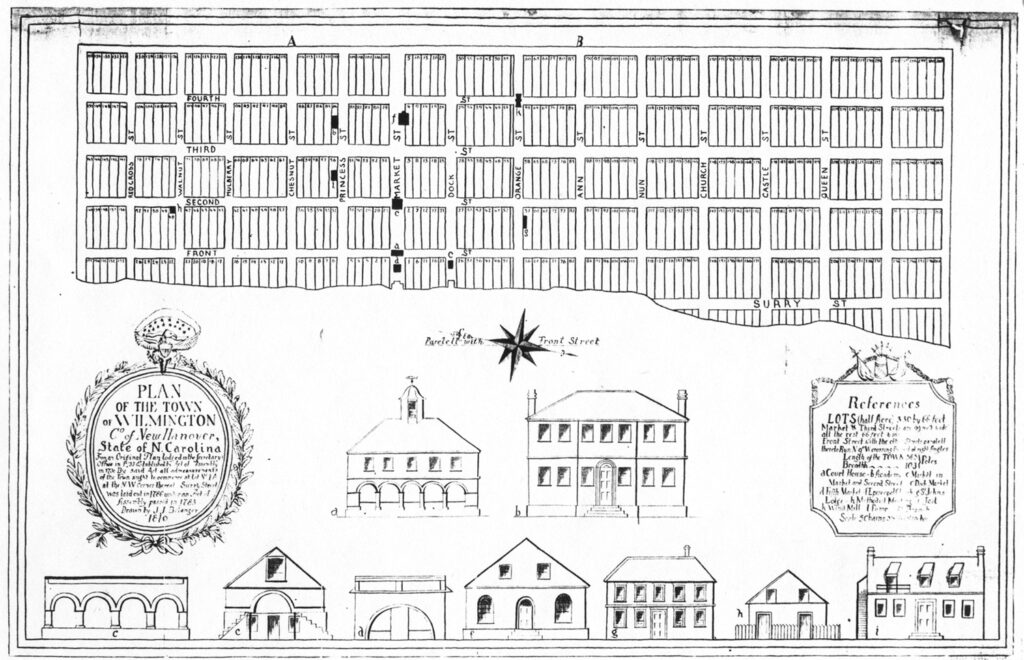

It can be found in the minutes of the Town Commissioners in May 1853, but the references are, at best, cryptic. What would eventually become Thalian was first referred to by commissioners who appointed a committee to seek a suitable site for a “public building to be used as a Town Hall.” No mention was made of a theater then, since Wilmington already had a performance space. Known as Innes Academy, it was a modest building 70 feet long by 40 feet by 30 feet high, including the foundation. It occupied the spot where Thalian Hall now stands, and it was the town’s principal theatrical venue for more than five decades.

It’s not clear what sparked the desire to replace Innes Academy, but Rivenbark had his own opinion. Although careful to state that his theory could not be fully documented, Rivenbark would tell the story of a visit to Wilmington in 1850 by the “Swedish nightingale,” Jenny Lind. On her way to Charleston, S.C., to perform, Ms. Lind’s train went through Wilmington. Learning of the presence of such an illustrious star, the town’s prominent citizens met the train with flowers in their arms and asked if she might perform here.

Her manager asked the size of the town’s theater, and when told the hall’s capacity, he replied, “Gentlemen, my orchestra would fill a large part of that space.”

Ms. Lind continued on to Charleston, leaving, Rivenbark conjectured, consternation in her wake.

“You can just see people talking at the saloon … or at the gentlemen’s club,” Rivenbark laughed, “or after church at St. James and saying, ‘We need a decent hall here. We missed out.’”

Innes Academy didn’t embody Wilmington’s vision of itself. This, Rivenbark explained, “was the largest city in the state, and it was the most prosperous and the most up-to-date. It was a status symbol at that time to have an opera house.” Wilmington, he believed, “had a sophisticated viewpoint.”

Trains were the era’s principal mode of transportation, as was the river. The town was a port and a rail center, and the citizens “had a view not only to New York but also to Europe,” said Rivenbark. Even Thalian’s Italianate style reflected current architectural tastes.

Amusements

Construction took more than two years, and early in 1858, with scaffolding still surrounding the building, Thalian hosted its first performance: a recital by Mr. Frensley’s Dancing School. The official opening was six months later, in October of that year, when Marchant’s Stock Company of Charleston performed two popular plays of the era.

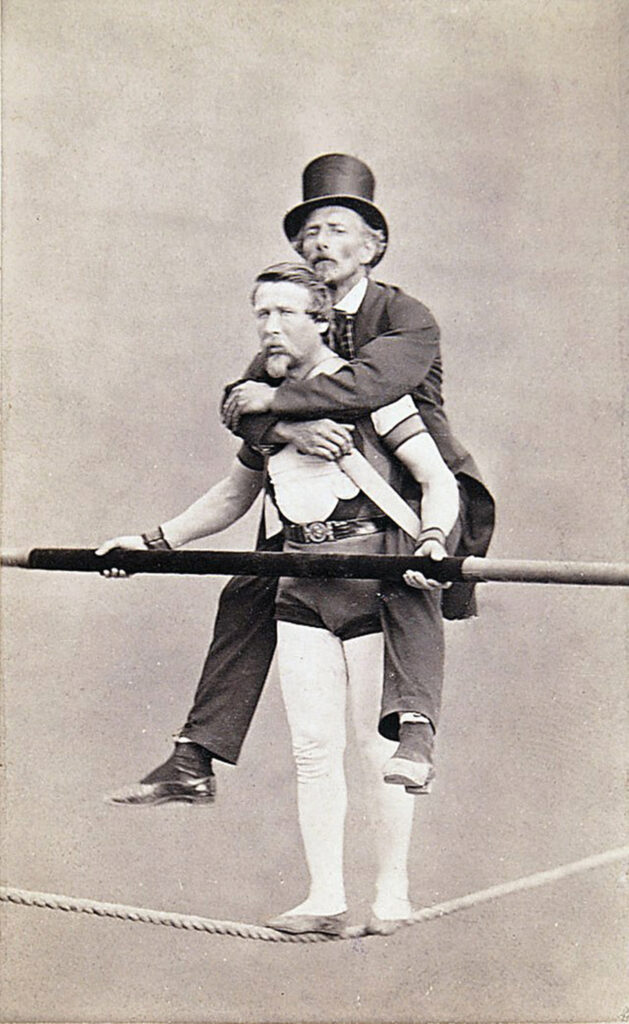

Marchant’s company remained in Wilmington into November 1858, performing a different play almost nightly. In December, the Thalian Association (whose name is still attached to a local community theater), presented two popular plays, including Box and Cox, a farce that had its most recent revival in 2008 as part of the Hall’s sesquicentennial. Thalian Hall’s first season saw further amateur productions, more stock performances, operas presented by the New Orleans English Opera Company, and appearances by the Martinetti and Blondin Troupe, which offered comic pantomimes and dances and featured Charles Blondin, a tightrope walker who became famous after crossing the gorge below Niagara Falls.

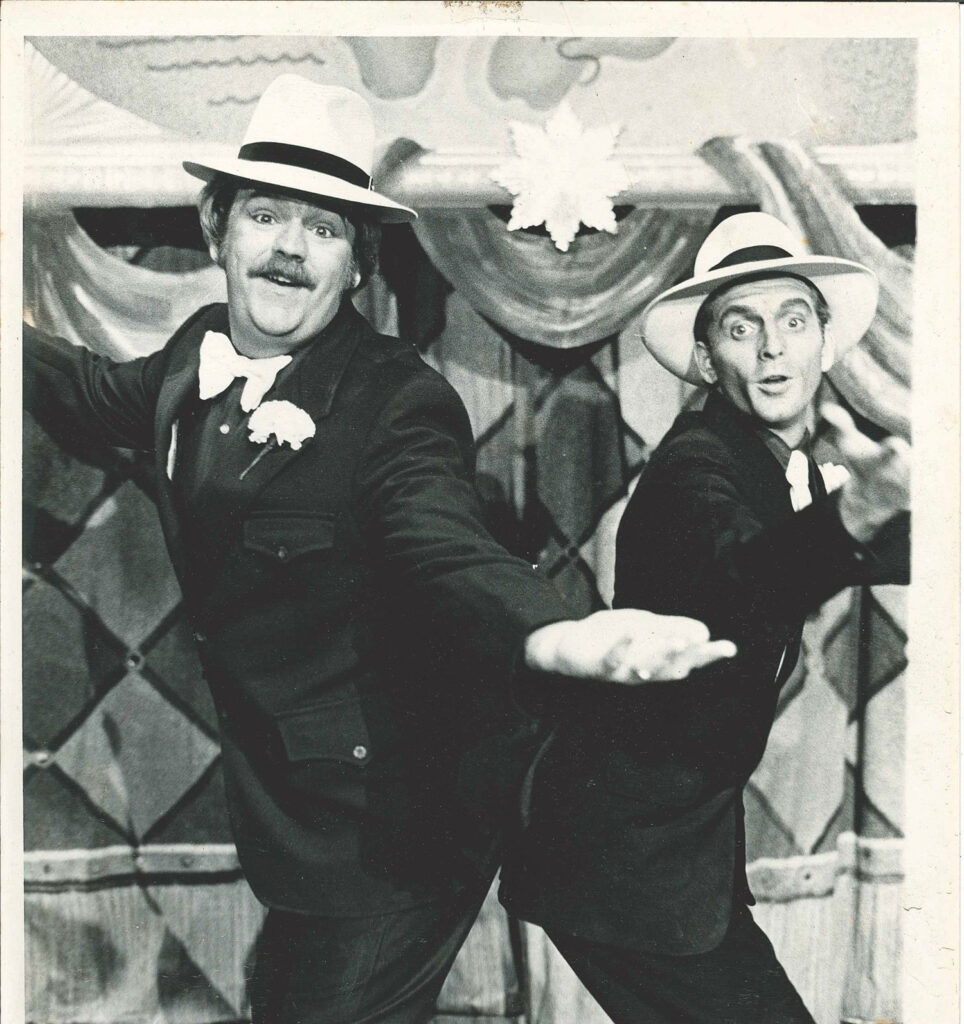

Thalian’s second season opened with a minstrel show, followed by another stock company and a 40-member troupe that presented a week of plays and spectacles.

Animals on stage

No amateur productions were mounted in 1859, but operas and road companies continued to visit, including Signor Donetti’s troupe of “Educated Dogs, Monkeys, and Goats.”

They were the first animals to appear on Thalian Hall’s stage, but certainly not the last. In 1869, actress Kate Raymond, scantily clad, rode her horse, Black Bess, across the stage in an adaptation of Byron’s epic poem Mazeppa. In the 1890s, an arctic play featured reindeer, sled dogs, three live bears and two St. Bernard dogs. Trained dogs often appeared and, in 1909 a circus play included three ponies, a trained donkey and a horse.

As interests changed, so did Thalian’s offerings. The mid-19th century had seen the rise of panoramas, and the Hall hosted Dr. Beale’s Wonderful Panopticon or Life-Moving Mechanical Exhibition of the War in India and the Sepoy Rebellion. It consisted of 80,000 models of men, women, horses, ships, artillery, cavalry, camels and other animals, presumably moving in front of a backdrop of panoramic paintings. The Daily Journal described the event: “The aquatic scenery, with ships and steamers moving about, is truly remarkable, as are also the battle pieces, with vast number of figures in actual march motion, cannon firing, etc.”

Thalian Hall Archive Collection

Later, another panorama drew crowds to the Hall.

It was, Rivenbark said, “New York City on a giant canvas.” Spools on either side of the stage turned 18,000 feet of canvas, revealing views of the buildings on more than 50 streets from Broadway to the Hudson River. The entire presentation took nearly two hours and apparently created the sensation of actually walking down the depicted streets.

Approaching war

As the Civil War approached, Wilmington turned away from amusements and focused more on the conflict to come, but Thalian Hall continued to play a central role in the life of the city, hosting political meetings at which the coming clash was undoubtedly a topic of discussion.

During the war, Wilmington grew. The port boomed. It was a blockade runners’ town. With money abundant and entertainment in demand, the Hall saw its most active period, except during the yellow fever epidemic of 1862.

Within a week of the town’s occupation by Union troops, the Hall reopened. Production initially thrived, but by 1867 both the town and the Hall were struggling. Eventually John T. Ford, a theater owner from Washington D.C., agreed to handle Thalian and added it to his touring circuit. As the town’s economy recovered, so did the Hall’s fortunes, and once again stock companies, hit plays from New York, and international performers visited.

Thalian Hall then and now

In the mid 19th century, most cities the size of Wilmington had an opera house. In the ensuing years, many of those buildings have been lost, and yet Thalian Hall still stands proudly in downtown Wilmington.

What makes it different? What makes a theater endure through changes in styles, interests, tastes and popular culture? Rivenbark, speaking with the perspective of an experienced theater manager, defined the question. “It’s all about making money. How can you make it go?”

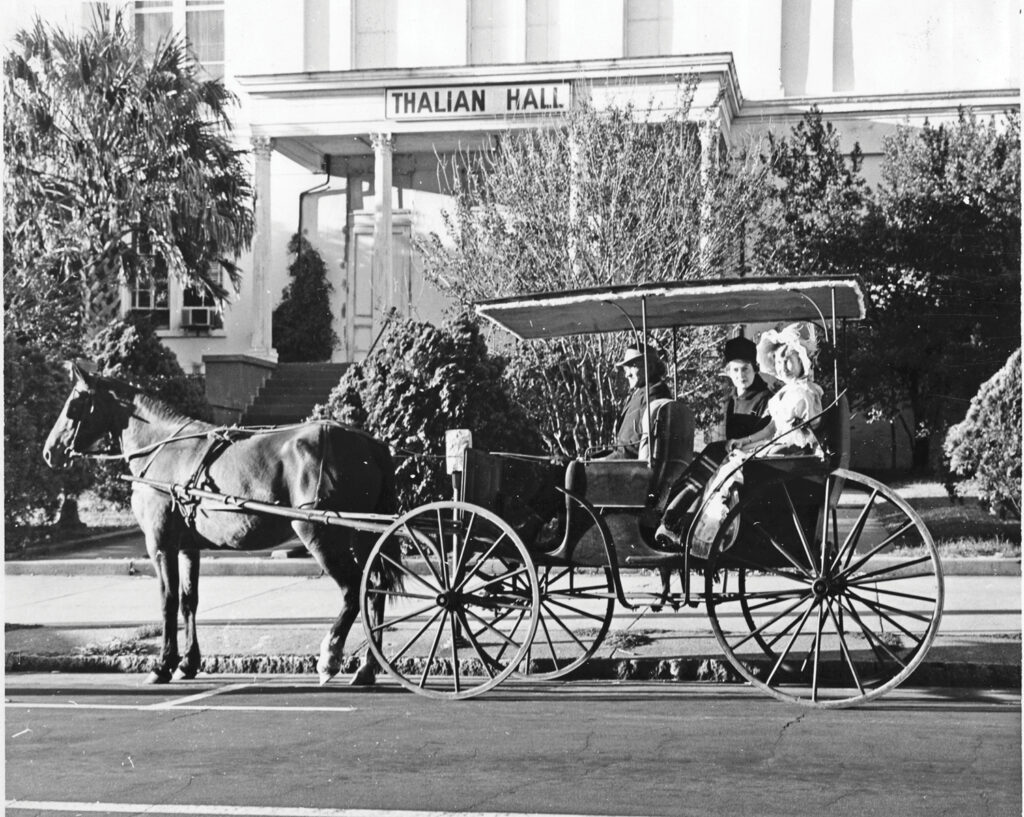

Tony Rivenbark outside Thalian Hall in 1994. The program in his hand is for a performance of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. Thalian Hall Archive Collection

Flexibility is essential. In fact, the Hall’s longevity may be due, at least in part, to its ability to capitalize on popular trends in entertainment. For instance, in the middle of the Reconstruction period, Rivenbark explained, “things weren’t going so great. [They] put in a new floor downstairs, remodeled it, and turned it into a dance hall. It didn’t last too long, but it was a fad.”

Indeed, the Hall has always responded to the desires of its audience. In 1871, the Star newspaper noted that it was possible for a skating contest to draw an audience away from a theatrical performance, so in the next decade, during a lull in professional engagements, Thalian installed a skating rink.

Thalian Hall has always been on the cusp of change.

Film begins

In 1897, before it even had electricity, it embraced the future of entertainment. When inventor Thomas Edison’s Projectoscope (also called a projecting kinetoscope) was booked for an engagement at the Hall, the Wilmington Electric Company spent all day wiring the theater so crowds could see the wonders of moving pictures projected across a canvas screen.

Rivenbark described that film as “pretty much a novelty” at the Hall, perhaps because there was more money in bringing in plays or because the theater was too big for showing movies to be economically viable. But Thalian refused to be left out of the nation’s growing fascination with the silver screen. Birth of a Nation was shown, accompanied by a full orchestra, and during the 1930s Shirley Temple movies were popular.

The history of movies at Thalian illustrates a surprising fact. While outward forms may change, the essence of theatrical entertainments often remains remarkably the same. Lecturers, for example, attracted large crowds during the Hall’s early years. One of the most popular was Oscar Wilde, who spoke on aesthetics and his theory of beauty. Temperance lectures were another big draw during Thalian’s early years.

Japanese acrobats, who were declared “the most wonderful jugglers in the world” when they performed at Thalian in 1867, were replaced in the 21st century by the stylized and athletic performance of the Shanghai Huai Opera, which performed in 2009.

Musical performances have proven to be a remarkably consistent part of Thalian’s history. Opera companies, as well as individual singers, visited with regularity, and operettas enjoyed wide acclaim. All kinds of vocal and instrumental groups have performed at Thalian, from all-female cornet bands to John Phillip Sousa, and from symphony orchestras to the U.S. Marine band. As with movies, many concerts have moved to more specialized venues, but a variety of musical acts continue to appear. The Hall has showcased classical pianists, jazz trios and even an African a cappella group.

Celebrities

As with music, celebrity appearances have long been a dependable element in Thalian’s appeal. During the age of “trouping” in the 19th century, star performers brought shows to all parts of the United States, including Southeastern North Carolina, but they occasionally encountered difficulties here. Companies traveled by rail, but although Wilmington was an important rail center, the trains’ timetables didn’t always accommodate actors’ schedules. Often performances had to be cut short to enable a company to catch the departure of the night train, much to the audiences’ dismay.

Still, celebrities visited Thalian Hall from its earliest days. Rivenbark explained that, in the 19th century, “the way people capitalized on their celebrity status was to create a play and travel around the country, because that was where the big bucks were.”

John L. Sullivan appeared in a boxing play, and Buffalo Bill Cody, before he developed his Wild West show, came to Wilmington twice. In 1875, he brought a “combination show” to Thalian that the newspaper called “a lavish expenditure of paint and powder.” He returned in 1875 with the play May Cody, or Lost and Won. After that performance, according to the Star, he “gave a short exhibition of his skill in handling the rifle.”

Other 19th century celebrities who visited were Joseph Jefferson (one of the most popular actors of the day, best known for playing Rip Van Winkle), and Tom Thumb (Charles S. Stratton), as well as James O’Neill (father of playwright Eugene O’Neill). And although the 20th century saw a marked decline in celebrity touring, Tyrone Power, Agnes Moorehead, Charles Lawton and Nelson Eddy also performed at Thalian. Later, nationally and internationally recognized stars, often actors who have called Wilmington home, have appeared on Thalian’s stage, including Linda Lavin, Pat Hingle, Peter Jurasik, Joe Gallison and Henry Darrow.

Amateur theater

Amateur theater has long been a mainstay at Thalian Hall, even though the kinds of performances have altered. In 1869, the ladies of St. John’s Episcopal Church presented an evening of Tableaux Vivant. These “living pictures” featured performers costumed (sometimes scantily) and arranged to reproduce famous paintings or statuary.

While such amusements were popular, audiences still preferred plays. As early as 1868, the newspaper declared that “the legitimate drama surely has enough admirers in Wilmington to support a first-class company here,” and in the same year, the Star carried a proposal that the Thalian Association Community Theater be revived. It was, and the group’s current incarnation continues to perform at the Hall, along with a number of other companies who also call Thalian home, among them Opera House Theatre Company.

Tony Rivenbark marked the celebration of his 35th year at Thalian Hall in 2014 with this photo by Belinda Keller

From its beginning, Thalian has embraced talented local performers, including Robert Howlette, a 19th-century Wilmingtonian who performed a tightrope act with an amateur “Humpty-Dumpty troupe” (a variety show that included acrobats, music and pantomimes.) He was so well received that he eventually left his job with the Star and performed with several circuses billed as “The Slack-Wire King.”

Production values as well as types of entertainment reinforce the notion that, “everything old is new again.” The modern era obviously offers technical advancements such as amplified sound, special lighting effects and sophisticated scenery, but audiences have always appreciated spectacle. In the 19th century, many theaters used a device called a “thunder roll” or “thunder run” to create the sound of an approaching storm.

At Thalian, the thunder roll consists of wooden troughs, suspended above the ceiling near the front of the stage. Cannonballs are dropped into and rolled through the troughs to create the rumble of thunder. While these devices were once common in opera houses, Thalian Hall is believed to possess the only one still in existence in the United States.

Nineteenth century performances at Thalian also were known to feature scenic effects that included a “brook of real water,” a “prismatic fountain with different colored jets,” and a railroad explosion. An arctic play even presented “glaciers and a snow storm.”

Technical advancements have been made on both sides of Thalian’s stage. Originally, the theater wasn’t especially comfortable. In the 1880s, a reporter noted that, “while our Opera House is a pretty one, it is certainly not a comfortable one.” On that night, the cold was apparently so bitter that the singer “shivered all over,” and she had to hold her music on the piano, “as the wind was constantly blowing it over.”

Switching gears

Audiences themselves have also changed. In Thalian’s early years, theater was an activity that was, according to Rivenbark, “almost like what television is to us.” Performances were widely attended by all segments of the population, although ladies usually frequented only those events that were considered appropriate. Or they might go to less acceptable ones wearing veils. Now women at Thalian are audience members, volunteers, performers, directors, designers, technicians and staff members.

During its 150th anniversary celebration in 2008, Thalian presented a series of events meant to both recall its past and celebrate its future. One of these was Toby Tyler or Ten Weeks with a Circus, a play based on a children’s book published in 1881.

Tony Rivenbark in the Thalian Hall auditorium in 2021. Photo by James Bowling

After the show, the audience exited the building through the south door facing Princess Street, originally the main entrance into the theater but largely unused for decades. No longer surrounded by the familiar stone and glass lobby, they emerged from the narrow, dimly lit hallway into the park where a crowd gathered on the lawn and suddenly, they could see Thalian through new eyes.

It was possible to envision an event the Star described in 1883. “… the park and hall were illuminated with Chinese Lanterns. The Cornet Concert Club played on the south portico, and a fireworks display on the lawn climaxed the evening.” In that moment, it was easy to see that with Thalian Hall, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Good bones

A newcomer to Wilmington might suppose that Thalian Hall has stood largely unchanged since construction was completed in 1858. This would, of course, be absolutely incorrect.

The 2009-2010 renovation is only one example of how Thalian has moved into the future while looking to the past for inspiration.

Nineteenth-century descriptions tell of a large gas chandelier that hung in the middle of the auditorium. As part of the 2009-2010 renovation Crenshaw Lighting of Virginia created an electric light replica, 7-and-a-half feet in diameter and 7-feet tall, with literally hundreds of faceted glass balls, rigged on a winch system, so that before the show, the houselights will go down and the chandelier will rise up.

Seating changes

Descriptions also tell us that originally the auditorium floor was level, the stage was raked (slanted down toward the audience) and the Dress Circle (first balcony) was a horseshoe-shaped structure with seating that came all the way to the front of the stage. The earliest photograph from 1910 of the interior post renovation reveals a stage now level and an audience now raked.

In the renovation of 1909, led by A. E. Schloss, who had been hired by the city to manage the theater, the balcony was cut back to its current configuration.

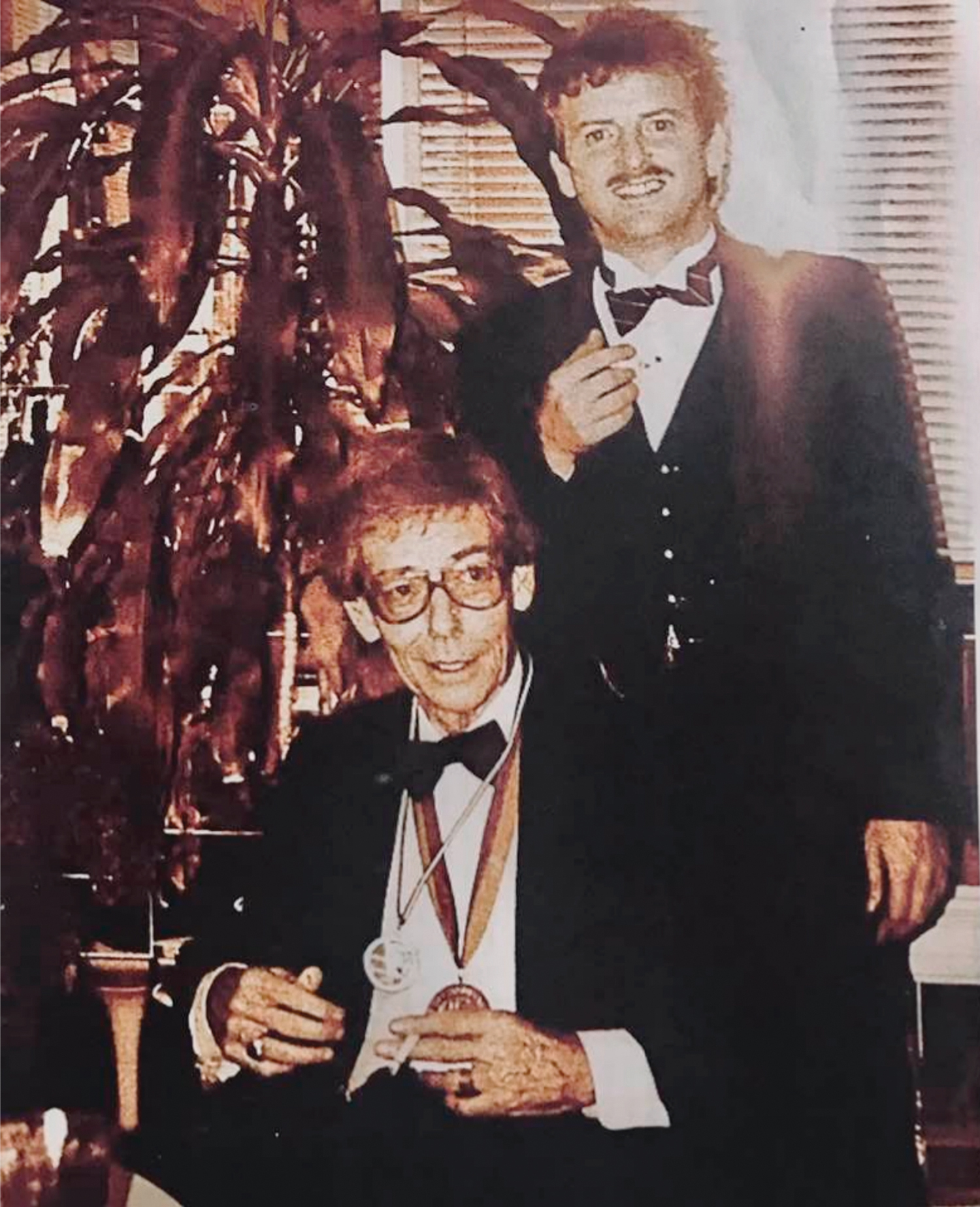

(1915-1997) and Tony Rivenbark (right) at a social function, circa 1980.

“The sightlines were terrible,” said Rivenbark, “so angling the front of the balcony around to the outside walls made sense.”

The elegant curves of the balcony lead many to believe the carpenters who built Thalian Hall had experience in Wilmington’s shipyards. The carpenters had access to the tools to make the kinds of bends and sweeps in large pieces of wood that were employed here. For example, the central section of the 12-foot-by-12-foot beam that makes up the front support of the balcony consists of only two pieces of wood, believed to have been steamed using some sort of large steam machinery to create that bow shape. Then they laid them on top of each other and sent a bolt through, connecting the two. It was all done by hand.

In 1909, seats in the Dress Circle were arranged in a series of tightly spaced straight lines. Also, no consideration was given to heating and cooling the balcony. The 2010 renovation addresses both these issues.

Several changes in the main seating area addressed audience comfort as well. In the 1950s, a steel beam was used to reinforce the front of the stage. This left the first few rows looking up at an uncomfortable angle. The relationship between the stage and the audience was returned to about what it was in 1858. The floor was raised a little over 12 inches. Not only are there larger seats with improved leg room on the Parquet (main) level, greater handicapped accessibility became available. The new cover for the expanded orchestra pit also improves the relationship between audience and stage. Operated by a hydraulic lift, the cover is raised and lowered by the touch of a button. Composed of the same material as the stage floor, it creates a seamless surface when raised to stage level. Or it can be lowered to bring a seated actor eye to eye with the audience. In 1990, the entrance to the theater was moved from Princess to Chestnut Street, and the lobby, box office and restroom facilities were expanded. The theater’s decoration was also addressed. Led by celebrated artist Claude Howell, this renovation restored much of the Hall’s multi-colored glory.

The 2009-2010 work built upon that foundation. John Sharkey and Chappy Valente, the lead artists, spent months working to accentuate the ornamental plaster work.

Joined at the hip

Thalian hall’s original hand-painted drop curtain has survived more than 164 years of wear and tear, and being lost and found a couple of times. In July 2016 after getting a makeover from a conservator at the Cameron Art Museum, the restored and revived curtain went on display in Thalian’s ground-floor lobby for all of Wilmington’s theatergoers and art lovers to appreciate.

Thalian Hall Archive Collection

Perhaps the most impressive thing about Thalian Hall is that it’s still standing more than one-and-a-half centuries after it was built. In all that time, “the city never wanted to be in the theater business, as minutes of the 19th and early 20th century City Council meetings show,” Rivenbark noted in 2010.

In 1900, City Alderman C. W. Worth told the council, “The Opera House is scarcely more than a mass of rotten timbers … it would be feasible, economical and desirable to tear away the Opera House …” From present to past, Mr. Worth would turn out to be wrong on several counts.

As for “a mass of rotten timbers,” that claim was definitively proven to be incorrect in the Hall’s 2009-2010 renovation, during which the floors of both the main floor (Parquet Level) and first balcony (Dress Circle) were taken up. Everything in the renovation of the first balcony has been built on top of that original framing.

Downstairs, on the Parquet Level, the original floor joists were rough-cut heart pine, two and a half inches thick by 13 inches wide. These timbers had an unsupported span of more than 40 feet in some cases. Astonishingly, the boards were totally clear — no warping, sagging, splitting or evidence of insect infestation. Unfortunately, they were taken out because they did not comply with modern codes. Instead, a series of support walls was built to carry the modern, engineered lumber that now serves as floor joists.

When they uncovered the structure, work crews found that the cast iron columns supporting the balconies had no nails, bolts or any mechanical attachments holding them to the piers on which they stand or the beams they supported — just gravity.

Thalian was threatened by fire in 1973, but Rivenbark said he didn’t believe that incident carried a threat of demolition. “Obviously, if the fire had been bigger …” Rivenbark said, voice fading at the dread of what might have been. The morning of the fire, “word spread that Thalian Hall was burning. And Doug Swink came down. Doug is the one who got the fire curtain down and in place. He probably saved the building.” Swink was a theater professor at UNCW.

The closest Thalian Hall has really come to being demolished was during the renovation of 1938, under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). One of the goals of the renovation was to create better access to the public library, which was then located on the second floor of the Hall. With only steep stairs in place, the city decided to install an elevator, and excavation for the shaft was done on the north wall of the building.

The wall next to the shaft “just wasn’t shored up properly. It might not have been necessary if it was hard ground, but because it’s basically loam,” said Rivenbark, voice trailing off. “So there was a wind that came through, and the whole north wall collapsed, which knocked out a huge chunk of what is now the mayor’s office.”

“All of a sudden,” Rivenbark continued, “people who were interested in having a new library or a new theater or a new city hall said, ‘Well, it’s a wonderful old building and all that, but it really doesn’t meet our purposes as a new city.’”

One issue was safety. The fear was that the building was not structurally sound.

“It was really the first major debate on preservation,” Rivenbark said. After engineering studies proved the structure of the building to be perfectly sound, the WPA secured the additional funds to do the necessary repairs, and the building remained.

Designed as a hybrid structure, Thalian Hall originally housed an armory for the Wilmington Light Infantry, two rooms for the Wilmington Library Association and, as it does today, city offices, a meeting room for public assemblies and receptions, and a theater. According to Rivenbark, “It was almost like they were trying to come up with enough uses for the building so they could make it really impressive. Which it is.”

Indeed, the conjoined nature of city offices and theater has frequently proved providential. When it was an appropriate time for a new theater, the city hall didn’t need work and vice versa.

“Being joined at the hip is, to me, why the building is still here,” Rivenbark said. “It’s what caused the building to be built, and that’s why, time after time, the building somehow wins out.”

The authors, Dorothy Rankin and Lee Lowrimore, relied on the research and scholarship found in the Thalian Hall Archives, especially that of Isabel M.Williams and D. Anthony Rivenbark.

The grand chandelier hangs above the audience seating. The reproduction installed in 2009-2010 is named “Alice” in honor of Alice Wine, whose husband, Jerry, gave it in her memory. WBM file photo

Thalian Hall Timeline

By Pat Bradford

1803 The trustees of the Wilmington Academy, under a bequest by Col. James Innes, began taking bids for the construction of a new building to house a theater.

1855 Construction began on a second, grander theater building, designed by renowned architect John Montague Trimble, who built 40 theaters before he went blind. Thalian Hall is the only Trimble theater still standing.

1858 The first performance. The original drop curtain was painted by Russell Smith. (It has been restored and is considered the oldest of its kind in the United States.)

1860-1936 The Hall was leased by private entrepreneurs.

1861-1865 The American Civil War.

1862 A yellow fever epidemic hit Wilmington. It arrived in August aboard the Kate, a blockade runner from Nassau. 650 died from the disease.

1867-1871 John T. Ford, who owned Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., where President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, leased the Hall, calling it The Wilmington Opera House.

1875 Buffalo Bill Cody came to Wilmington to perform twice.

1880s Thalian installed a skating rink.

1886 An electric light was installed at the entrance.

1897 The first movies were shown, using a Projectoscope invented by Thomas Edison.

1898 Electricity installed throughout the building.

1909 A circus play included three ponies, a trained donkey and a horse.

1909 Renovations cut back the side balconies and the ornate proscenium. Electric stage lights were installed.

1928 Ziegfield Follies, one of the last of the traveling musical revues, came to town.

1938 The north wall collapsed during renovation to install an elevator under the Works Progress Administration (WPA), funded by a $50,000 grant.

1963 The Thalian Hall Commission was formed and incorporated, and money was raised to upgrade the theater and make improvements.

1966 An 18-year-old Tony Rivenbark auditions for a production of “Good News,” a collaboration between Wilmington College and Thalian Association.

1970 The Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

1973 Following a small fire on the first floor that destroyed the decor, the theater was returned to its turn-of-the century appearance.

1975 The Hall reopened after fire damage.

1985 A $1.7 million bond for renovation and expansion was passed.

1985 The name was changed to Thalian Hall for the Performing Arts.

1988 A $5 million project to expand Thalian Hall and City Hall began. It took 18 months.

1990 The entrance to the theater moved from Princess to Chestnut Street. The lobby box office and other facilities were expanded.

1990 The theater was renovated and redecorated, led by celebrated artist Claude Howell.

1990 To celebrate the grand reopening of the newly improved Thalian Hall /City Hall on March 2, a two-week performing arts festival was presented by visiting artists and local art organizations.

2003 A new master plan was completed, with more renovations and the creation of a medium-sized playhouse adjacent to the present stage.

2007 The General Assembly designated Thalian Hall as the official community theater of the state of North Carolina.

2008 Linda Lavin headlined the 150th anniversary celebration.

2009-2010 Another $4 million renovation took place, preserving historical aspects of the theater and adding new technology and box office and lobby facilities.

2022 Tony Rivenbark, executive director of Thalian Hall Center for the Performing Arts for 42 years passed away.

Uncovering history

Who Built Thalian

The 2009-2010 renovation brought the original framing of Thalian Hall to light, including a complicated piece of joinery supporting the center of the balcony. Called a “valley joist,” all the connections are made by mortise and tenon construction, with no nails. Every joint meets perfectly with no gaps. And everything was cut with hand tools.

Who were these master carpenters? According to Beverly Tetterton, curator of the North Carolina room at the New Hanover Public Library, they were African slaves. “They built Thalian Hall, Fort Fisher, the Market House, as well as most of the finer homes in downtown Wilmington,” she said at that time.

Hired out by their masters to work on large construction projects, the slaves did the work and the masters were paid. Quartered in “slave yards” next to the construction site, these men were sent to Wilmington from plantations all over Southeastern North Carolina.

Segregation

Thalian Hall was certainly segregated even though the city was one of the most integrated towns around. But Rivenbark believed that economics became the deciding factor. “In the end,” Rivenbark said, “it’s all about making money and selling tickets.”

When artists appeared who appealed primarily to a black audience, Rivenbark believed that “they would put all the black people downstairs and put the white people in the balcony.” When Booker T. Washington spoke in 1910, “they basically divided the house in half; it had a center aisle, so they put the blacks on one side and the whites on the other,” Rivenbark said.

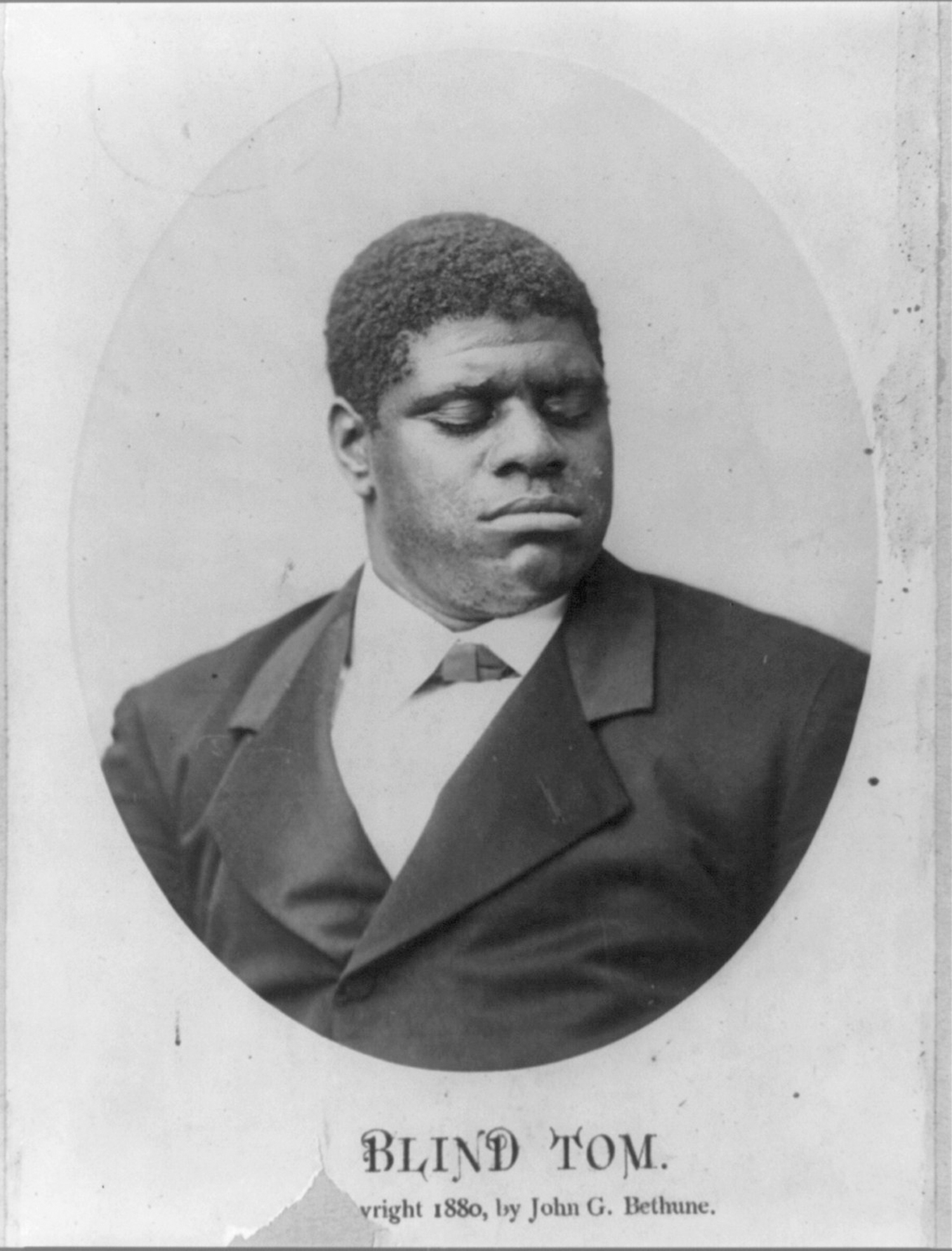

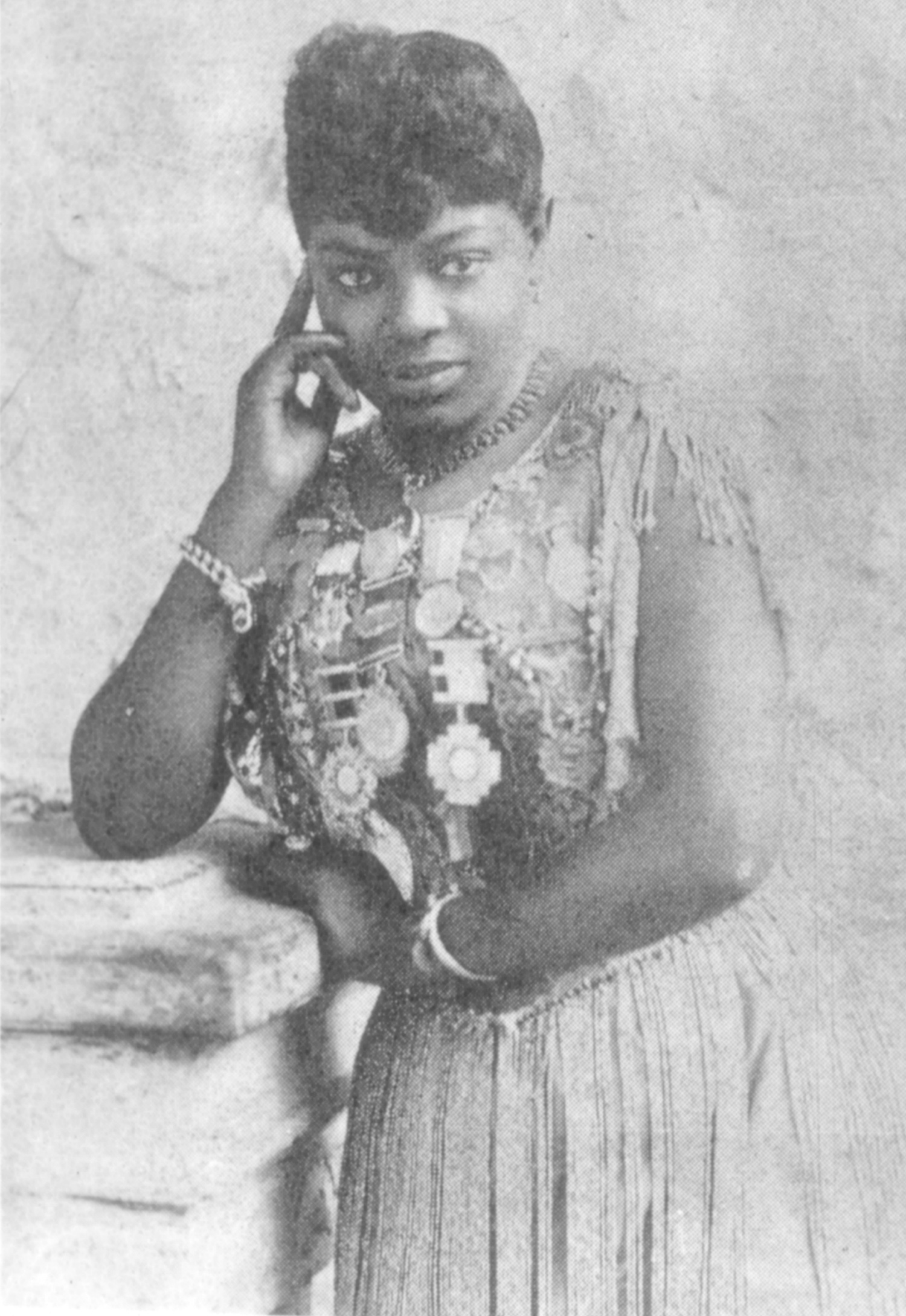

A variety of black entertainers appeared. Musical savant Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins (also called Blind Tom Bethune) played the piano at Thalian, appearing before the war as a slave and afterward as a free man. Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, an opera singer and vaudevillian, who was known as “The Black Patti” (referring to Adelina Patti, a famous Italian opera singer of the day), also performed there, and the theater hosted classical singers Marian Anderson and Caterina Jarboro.

Local black amateurs have a continuing history at Thalian. In the 1890s, the Acme Club, which consisted of 48 black musicians, appeared, as did The Willis Richardson Players (named for a black playwright born in Wilmington).

In 1870, a small group of men used Thalian to test the response of the community to blacks sitting in sections designated for whites. When they were ejected, they sued the theater. The judge who heard the case chastised them, but he also ruled that blacks were “entitled to accommodation and privileges in this theater equal to those enjoyed by other persons.”

Clearly, times were changing, and Thalian Hall would change with them.