Carolina Bays

BY Andy Wood

Enigma n. One that baffles the understanding.*

*Websters Dictionary

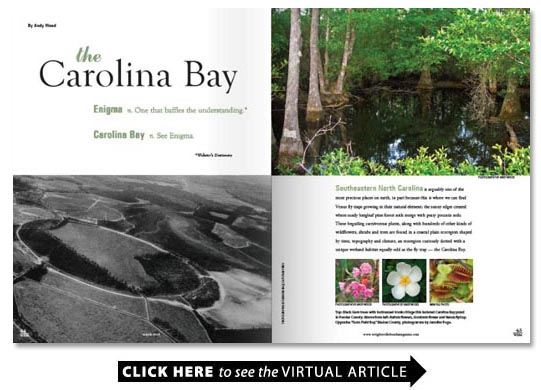

Southeastern North Carolina is arguably one of the most precious places on earth in part because this is where we can find Venus fly traps growing in their natural element; the sunny edges created where sandy longleaf pine forest soils merge with peaty pocosin soils. These beguiling carnivorous plants along with hundreds of other kinds of wildflowers shrubs and trees are found in a coastal plain ecoregion shaped by time topography and climate an ecoregion curiously dotted with a unique wetland habitat equally odd as the fly trap the Carolina Bay.

Carolina Bays also simply called bays are so-named for trees in the

The origin of Carolina Bays is more likely owed to long periods of ice age winds during the Pleistocene Period (2 588 000 to 11 700 years before present) when northern North America was covered by an ice sheet more than a mile thick and the Atlantic coastal plain was much colder than present day conditions. During that bygone time our region was populated by forests of spruce and hardwood trees scattered across vast expanses of open plains. Much as we might want a definitive answer to the question of bay origin scientific consensus remains distant.

By most interpretations persistent winds are the likely cause sweeping over wide areas of deep sands sometimes covered by shallow water over time scouring oblong depressions as a result and eventually becoming wetland and pond ecosystems we know today as the

Unproven origin theories aside I can attest that few places are more fun to explore than a Carolina Bay for a sensory experience highlighted with aromatic smells of cypress tree oils and the sweet fragrances of innumerable flowers including blooming loblolly and Virginia bay trees.

Carolina Bays and a related habitat locally known as pocosin have a complex forest structure topped by tall canopy trees including pond cypress (Taxodium) and pond pine (Pinus) shading a forest midstory composed of red bay loblolly bay (Gordonia) Virginia bay (Magnolia) alongside black gum (Nyssa) various oaks (Quercus) and red maple (Acer).

Growing under the midstory trees are flowering shrubs including Cyrilla Clethra Lyonia Zenobia and Leucothoe. Dozens of other plant species many with equally quizzical names are also found in bays and pocosins intertwined by cable-like woody greenbrier vines adorned with needle sharp spines that trip-up clumsy feet and poke through the toughest clothing.

Pocosin a word coined by early Algonquin-speaking Native American peoples has long been translated to mean swamp on a hill a fitting moniker for a wetland shrub thicket habitat that fills low places between otherwise elevated sand ridges where longleaf pines grow.

In addition to supporting a great diversity of plants

While you and I might stumble ineptly through a bay or pocosin tangle Ive watched adult black bears slip through the densest underbrush as though they were passing through a cloud. When struggling through a pocosin thicket it is funny knowing every living animal within earshot knows where I am while I have little clue where they are.

Exploring a

Around some ponds you will find vestiges of those ancestors in the form of rotting stumps some showing black scorches wrought by past fires that swept through the area especially during periods of drought.

Entering one of these places is a humbling experience knowing you are stepping on soil built up from leaves and stems produced by uncounted generations of trees each generation with a lifecycle possibly spanning many hundreds of years. Kneeling at the buttressed trunk of a living cypress ten times my age or more provides a clear sense of being in a hallowed place.

Passion aside scientific studies of pollen trapped in

With my minds eye I can imagine that icy period when Carolina Bays served as bathing and drinking areas for bison musk ox and the now extinct giant ground sloth along with the great predators that hunted them including saber-toothed cats lions wolves bears and early American Indians.

Through thousands of years these ponds have continuously served people and wildlife with water food and shelter though now instead of bison and lions we find deer and bobcats along with my favorite Carolina Bay inhabitants frogs toads and turtles.

Today many of our Carolina Bays are mere shadows of what they once were as seen in aerial images that reveal oval areas neatly cross-hatched with crops of one type or another. Such conversions reduce ground and stormwater storage capacity leading to flooding during heavy rain events and water shortages during periods of drought. These consequences on top of diminished wildlife populations are due simply to habitat loss.

Fortunately efforts to identify and protect Carolina Bays are underway by state and federal agencies in concert with conservation organizations. This good work is not just for the benefit of birds frogs and wildflowers; Carolina Bays provide tangible ecologic and economic value with water as their priceless currency.

Exactly how Carolina Bays came into being may remain unknown for years to come and thats fine. Their mystery offers current and future ecologists and conservationists something to investigate and ponder. In my view the more pressing question

to answer in this modern world what some call the Anthropocene is how we will hold a place for Carolina Bays so they may continue to provide services to the benefit of whole communities people plants and wildlife combined.