Art Treatise: Maritime Art

BY Marimar McNaughton

From the wilds of Roanoke Island to the back roads of Harkers Island intrepid artists plunder the coast for subject matter. Time and again boats in yards is a universal theme.

ROBERT IRWIN

Robert Irwin shelved a myriad of careers to adopt the life of an artist.

The former cruising sailor and motor yacht crewman found safe anchorage on a sublime slice of paradise amid a treed landscape that screens a woodland studio on property backing up to deepwater near Beaufort North Carolina.

“I painted work boats sailboats and toward the end I got very interested in the Carolina flare and the angle you got when standing under them in the yard ” Irwin says. “These big boats are just spectacular.”

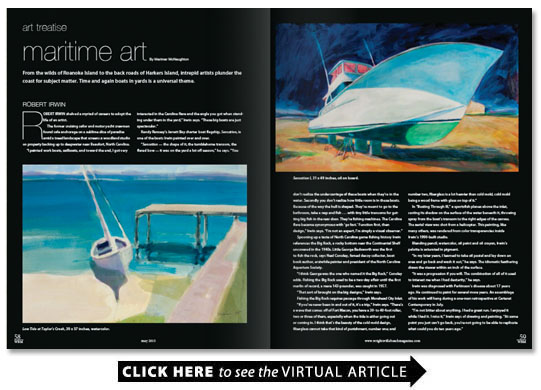

Randy Ramsey’s Jarrett Bay charter boat flagship Sensation is one of the boats Irwin painted over and over.

“Sensation — the shape of it the tumblehome transom the flared bow — it was on the yard a lot off season ” he says. “You don’t realize the undercarriage of these boats when they’re in the water. Secondly you don’t realize how little room is in these boats. Because of the way the hull is shaped. They’re meant to go to the bathroom take a nap and fish . . . with tiny little transoms for getting big fish in the rear door. They’re fishing machines. The Carolina flare became synonymous with ‘go fast.’ Function first then design ” Irwin says. “I’m not an expert I’m simply a visual observer.”

Spooning up a taste of North Carolina game fishing history Irwin references the Big Rock a rocky bottom near the Continental Shelf uncovered in the 1940s. Little George Bedsworth was the first to fish the rock says Neal Conoley famed decoy collector boat book author erstwhile painter and president of the North Carolina Aquarium Society.

“I think George was the one who named it the Big Rock ” Conoley adds. Fishing the Big Rock used to be a two-day affair until the first marlin of record a mere 143-pounder was caught in 1957.

“That sort of brought on the big designs ” Irwin says.

Fishing the Big Rock requires passage through Morehead City Inlet.

“If you’ve never been in and out of it it’s a trip ” Irwin says. “There’s a wave that comes off of Fort Macon you have a 30- to 40-foot roller two or three of them especially when the tide is either going out or coming in. I think that’s the beauty of the cold mold design fiberglass cannot take that kind of punishment number one; and number two fiberglass is a lot heavier than cold mold cold mold being a wood frame with glass on top of it.”

In “Busting Through III ” a sportsfish planes above the inlet casting its shadow on the surface of the water beneath it throwing spray from the boat’s transom to the right edges of the canvas. The aerial view was shot from a helicopter. This painting like many others was rendered from color transparencies inside Irwin’s 1990-built studio.

Blending pencil watercolor oil paint and oil crayon Irwin’s palette is saturated in pigment.

“In my later years I learned to take oil pastel and lay down an area and go back and wash it out ” he says. The idiomatic feathering draws the viewer within an inch of the surface.

“It was a progression if you will. The combination of all of it used to interest me when I had dexterity ” he says.

Irwin was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease about 17 years ago. He continued to paint for several more years. An assemblage of his work will hang during a one-man retrospective at Carteret Contemporary in July.

“I’m not bitter about anything. I had a great run. I enjoyed it while I had it. I miss it ” Irwin says of drawing and painting. “At some point you just can’t go back you’re not going to be able to replicate what could you do ten years ago.”

CHIP HEMINGWAY

Chip Hemingway bounces from project to project from the southern edges of the North Carolina coast to its northern fringes but one thing remains constant: He’s always packing an easel some brushes and tubes of paint.

Architect by training artist by nature Hemingway paints the barn he bought beside Tannehill near Shandy Point in Wilmington North Carolina. The 1 900-square-foot space will soon become his artist studio not far from the Intracoastal Waterway.

“I paint what’s right in front of me. I choose my subjects based on the light and the composition and the underlying story behind the painting ” Hemingway says.

A native son of Tarboro North Carolina he drives from his home in Wilmington to the Outer Banks where he has designed new conference meeting and research facilities for North Carolina Audubon at the old Pine Island Hunt Club north of Duck.

“To me the beauty of the Outer Banks is nature still rules what you’re gonna do ” Hemingway says.

These trips to Pine Island are not a new thing for him. His architectural design projects include Jeannette’s Fishing Pier Oregon Inlet’s Coast Guard Station and the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island. While working on aquarium renovations he met Neal Conoley.

“Neal Conoley and I were riding around trying to figure out what we were going to paint ” Hemingway says “as we often do.” One day about four years ago Conoley took Hemingway to meet Omie Tillett.

When they walked into Tillett’s backyard the legendary game fisher and boat builder stood up and raised his arms into the air and threw them around Conoley in greeting.

“He was sitting in his backyard with his homemade clam splitter ” Hemingway says. “There’s a huge pile of clams beside him.”

A Manns Harbor shad boat painting comes with a story too of the lecture Hemingway caught from a bystander about how stupid it was gill net fishing had been outlawed.

“I’ve tried to do . . . paintings that showed the lifestyle of eastern North Carolina living which a lot of times is related to the water ” Hemingway says. “I just paint wherever I go.”

JOHN SILVER

Manteo artist gallery and studio owner John “Possum” Silver is building a boat with his son John.

“He’s a commercial fisherman and he wants to go up in size so I found an old Chesapeake Bay hull ” John Silver says.

The classic dead rise had fallen to pieces Silver says but the fiberglass hull was still in good shape. The father and son team gutted and refit the boat buoyed by the expertise of the Wanchese boatbuilding elite is well past the three-month mark.

“I’ve gotten great insight into renovating boats ” Silver says. “Everybody in Wanchese is so helpful it’s like the foundation of this world I think. They all know so much and I don’t have to know anything but ask the right questions and here they come. Their sharing is an amazing experience for me. I have reconnected with all the culture how technically genius they all are — Buddy Davis’s son Patrick Harrison and Max Jones they’ve all built boats and are willing to share their knowledge.”

Silver’s brother Winkie owns Wanchese Dock and Haul.

“Whenever the old boats come in he gives me a heads up and I paint the old boats on poppits because of the shape. As time goes by there’s fewer and fewer of them and they look so good up there the bottom paints the tints. I have painted quite a few. Just about each one has a little story with it ” Silver says.

“It really shows the character of the keel ” he says. “The whole shape of the boat is so beautiful to me.”

KYLE HIGHSMITH

From his urban Raleigh home or his country farm professional painter Kyle Highsmith has driven the road less traveled eyeing arcane artifacts of vanishing cultural icons that become subjects of his en plein air paintings. For decades he has plundered the coast of North Carolina in search of boats. One boat he says he painted a couple of times about 15 years ago was a 60-footer built in the front yard of a house trailer.

“It wasn’t a company a large operation ” Highsmith says “it was somebody who learned the craft from somebody for his own use.”

Both in and out of the water boats surface time and again in his works.

“Things that are handmade things that use local materials that are from the culture are very much a representation of the South where the boat-building industry has been a local occurrence in the last hundred years ” Highsmith says.

The appeal of those things he says show hands-on workmanship.

“I love North Carolina handmade duck decoys. I own duck decoys. I enjoy looking at them ” Highsmith says.

He compares the knife marks around the decoy body and the bill to the same quality he finds in traditional wooden boatbuilding.

“I’ve done a fair amount of painting in Harkers Island ” Highsmith says describing a scene he drove up on one day.

“The bow of the boat was sticking out of the shed. They were still planking the boat ” he says. “You go up and see where somebody has worked each individual piece of wood. It’s just so fascinating to see that; I’m sure they make wooden boats in other places. … I think it’s a representation of the culture of North Carolina.”

Highsmith appreciates the indigenous Harkers Island boat form: the vertical bow the flat bottom.

“The sides sweep down have the most wonderful curve ” he says. “Typically they’re not going out far from shore. … The smaller boats used for fishing the sound not more than five miles from shore most of the larger ones are older boats are wooden.”

Highsmith’s boat paintings have floated around the state’s fine art galleries and fine dining restaurants notably the Irregardless Cafe in Raleigh where he trades canvases featuring subsistence-based fishing boats for meals.