An Artist Lost

BY Robert Rehder

In June 1971 the popular New Hanover Fishing Club Magazine featured a photograph of its secretary-treasurer Nick Giovinetti one of the Cape Fear region’s most colorful outdoor personalities. Tanned rugged in his late 20s with aquiline features and dark eyes that flashed when he spoke of his experiences in the wild Giovinetti enjoyed an enviable reputation as a journeyman outdoorsman fisherman and waterfowl hunter. Wrightsville Beach was his base but from there he roamed and fished camped hunted and explored every lonely spit of beach every winding cut of water and all the wind-torn tide-ravaged salt guts and bays from Bald Head to Bear Inlet. If anyone in this world ever felt the draw saw the power and heard the harmony of wind and sea and wild it was Giovinetti.

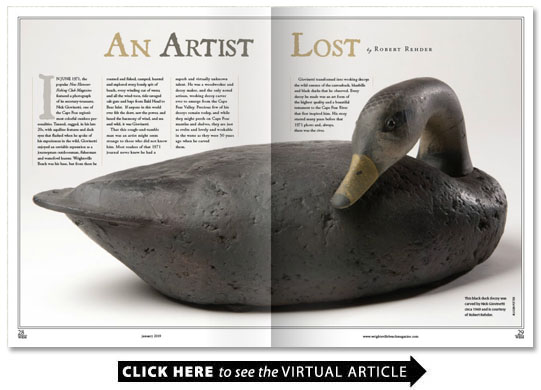

That this rough-and-tumble man was an artist might seem strange to those who did not know him. Most readers of that 1971 journal never knew he had a superb and virtually unknown talent. He was a woodworker and decoy maker and the only noted artisan working decoy carver ever to emerge from the Cape Fear Valley. Precious few of his decoys remain today and while they might perch on Cape Fear mantles and shelves they are just as svelte and lovely and workable in the water as they were 50 years ago when he carved them.

Giovinetti transformed into working decoys the wild essence of the canvasback bluebills and black ducks that he observed. Every decoy he made was an art form of the highest quality and a beautiful testament to the Cape Fear River that first inspired him. His story started many years before that 1971 photo and always there was the river.

Nick Giovinetti’s Hunting Grounds

From 1950 through 1990 the Cape Fear River Basin offered the finest duck hunting on the East Coast. Back then beginning in October of each year the confluence of the Northeast the Brunswick and the Cape Fear Rivers near Wilmington drew wild mallards black ducks wood ducks and green-winged teal by the thousands and by Thanksgiving the boom of shotguns was heard echoing through area marshes. When waterfowl season was in full swing names like Horseshoe Bend Clearwater Bayou Toomer’s Creek and Eagle Island — most still visible from Wilmington’s major bridges today — were home to migrating waterfowl that arrived each winter. They came to roost in the fresh water marshes and browse on the abundant wild rice that matured each fall.

The upper marshes near Wilmington were just part of the great river’s waterfowl draw. The lower reaches of the Cape Fear were equally spectacular. Winter arrived early in those years bringing the fierce northwest winds of November. Riding the storms south into the broad expansive sounds and bays of the lower Cape Fear near Clarendon Pleasant Oaks Big Island and Orton came bluebills ring-necked ducks and prized bull canvasbacks spiraling down through the icy skies.

Farther east toward the ocean where Giovinetti loved to hunt the estuarine spartina expanses of Southport Sunny Point Bald Head Island and Buzzards Bay brought widgeon gadwall and the lovely acrobatic pintails which poured into places called Cedar Creek Gum Log Branch and Molasses Cove.

Art of Carving

With ducks came duck hunters who deployed a “spread” of decoys — the primary method used to hunt waterfowl — sometimes as few as a dozen but more often a “raft” of 50 or more placed in the water in certain patterns near a makeshift blind. Superb as the hunting was the Cape Fear watershed never saw hunting guides decoy carvers or boat builders like those who prospered in the state’s northern waters of Core Sound Ocracoke and Currituck.

Early North Carolina decoys were carved from local wood — juniper cedar or pine and made for durability. Hunters were rough on decoys stacking them by the dozens into small boats with heavy weights wrapped around the decoy’s neck. Enter the Herter’s Company of Waseca Minnesota that brought to the market its Model 63 Standard and Model 72 Magnum decoys made from lighter inexpensive durable plastic.

But those early decoys hand-carved by artisans were soon to be recognized as art forms because for many hunters the beauty and elegant style could never be duplicated by utilitarian plastic varieties. One of those hunters was Giovinetti.

At the height of the waterfowl era of the Cape Fear region in a small workshop on Chestnut Street renowned woodworker George Paylor (1937-2016) began mentoring the emerging artisan carver. Under Paylor’s watchful eye Giovinetti worked alone and later with two duck-hunting friends Charles Godwin and Dave Gustafson to produce his exemplary working decoys. Perhaps it did not occur to them at the time that they were not just making a functioning decoy but a work of art. Some carved decoys of that era were produced simply for display but not Giovinetti’s. In the enduring context of working models his canvasback decoys weighed almost three pounds each and graceful as they were to look at on land they worked like a charm in the roughest waters.

The body of a Giovinetti decoy was made from dense cork that was reclaimed and fashioned from the refrigeration units of WWII Liberty Ships. The tail pieces and keels were sawn from local juniper and the bottom boards were of marine plywood. The heads were hand-carved kiln-dried hardwood painstakingly primed painted and feathered. Glass eyes were attached and then hand-cast lead ballast weights were affixed to the keels with brass screws.

While the initial technical woodworking expertise must be attributed to George Paylor’s skilled influence all art form first requires inspiration. For that one need only to observe Giovinetti who was profoundly inspired by nature. He was born and reared in Wilmington; graduated from New Hanover High School and Wilmington College and was for some time a high school teacher in Brunswick County. He was devoted to his wife Martha Lee and their young son Matt. The formative experiences of his youth — those that would shape his adult life — took place on the Cape Fear River several miles south of his 22nd Street Chestnut Heights home. The river was his teacher and it was there he first learned the ways of waterfowl.

Hunted Every Day

During high school and between college classes Giovinetti hunted every day he could of every duck season. As a youngster he began with ducks and a Belgium Browning shotgun and to ducks he turned as an adult with a file saw and wood rasp. While he might not have admitted it and despite early setbacks he had evolved into a premier woodworker and decoy maker. But in the beginning and in the end with his faithful Labrador retriever Drake he was first a duck hunter.

His love of the Cape Fear did not keep him from exploring other river systems and the New River estuary was one of his favorites. TheNew River flows east-southeast meandering throughthe sprawling Camp Lejeune Marine Base in Onslow County north of Wilmington. Eventually it becomes a wide brackish tidal bayflowing finally to the Atlantic Ocean through New River Inlet. When winter winds whip down the bay and kick up against a rising tide the usually placid waters become as rough-cut and supremely dangerous as any on the North Carolina coast. As if churned by some huge paddlewheel the waters become ripped with cross currents and laced with smothering white-capped waves. Into the midst of this cauldron oblivious to the surging slough of water thousands of bluebills and canvasback ducks returned each year.

Final Hunt

In 1972 the ducks picked late November to arrive and raft after raft migrated into the New River basin during the week of Thanksgiving. In the midst of the migration on Saturday November 26 two days after Thanksgiving Day Giovinetti made his final hunt.

The day broke cold pale and heartless as gusting winds pushed heavy gray clouds over the choppy waters — ironically just the kind of day a duck hunter longs for. The conditions would indeed make for an excellent hunt one that should have been remembered and discussed with pride and respect for years to come among his many waterfowling friends. Only this one turned tragic when the afternoon grew dark and the storm intensified.

While his many companions friends and family will never know exactly what happened that fateful night we know simply and finally that he perished as he made his way back to the distant landing after dark when his boat swamped and capsized in rough water. Nicholas Carmon Giovinetti III was 29.

In the short few years that he carved it is estimated that Giovinetti produced fewer than 100 decoys primarily bluebills and canvasbacks. He carved only six black duck and six goldeneye decoys of which only two goldeneyes are known to exist today. Many Giovinetti decoys were lost as a result of the accident and few remain of any kind today. The last known pair was purchased from an Outer Banks dealer by a Wilmington hunter and investor for an undisclosed sum.

While Giovinetti designed each decoy as a working model each is also a work of art and lends perspective to a waterfowling culture that was once a social and economic driver along the North Carolina coast. Giovinetti’s decoys transcend an ordinary sportsman’s experience and serve as a venerable and graceful reminder of our coastal heritage.