Alien Invaders

Non-native plants can morph from marvelous to monstrous

BY Melissa Sutton-Seng

At the 1876 World’s Fair Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, the American public was introduced to the telephone, Heinz Tomato Ketchup, the steam-powered monorail, and bananas. Also on display was an ornamental plant with bright purple flowers and broad, dark green leaves. Fairgoers marveled at its amazing rate of growth — up to a foot a day.

Kudzu had come to America.

Brought from Japan and promoted as a “wonder vine,” kudzu for years remained somewhat of a novelty, an ornamental plant with sweet-smelling blossoms sometimes grown to shade patios and courtyards. Then came the drought, dust storms, and infrastructure expansion of the 1930s and ’40s. Kudzu was promoted as a cure-all for erosion, soil depletion, and lack of livestock feed.

Thus “the green scourge” began its invasion of the Southeast.

Less than 100 years later, kudzu is everywhere, or at least it appears that way. Kudzu flourishes best in the areas we see most often from our cars — roadsides, abandoned structures, and the edges of forests — but it grows poorly in shaded spots and is beaten back by foraging animals. In recent years, an insect known as the kudzu bug found its way here from Japan and is helping keep the vines in check.

As it turns out, the green scourge is something of a red herring. Yes, kudzu is invasive, can be detrimental to native species, and ought to be eradicated whenever possible. Still, it’s not the worst invader among us.

Just as kudzu was once sold as an ornamental plant and then promoted as an agricultural panacea, a significant number of other non-native species have been introduced in Southeastern North Carolina, many of them doing more damage than kudzu ever has.

What makes a plant invasive?

An invasive plant is any species not originally from a region that, once introduced, grows vigorously, outcompetes other plants in the area, and is difficult to control. They cause damage to the local ecosystem, economy and/or human health.

Not every frustrating plant is an invasive species, and not every species introduced to an area becomes invasive. Vines like Virginia creeper and poison ivy are aggressive and annoying, but they are native to North Carolina and serve a purpose in our ecosystem. The evergreen azaleas for which Wilmington is so well known originated in Japan, but unlike kudzu they aren’t invasive and can be recommended for landscaping without concerns about negative impacts on the local ecosystem.

Non-native plants have different impacts in different ecosystems. Originally from China, butterfly bush (Buddleja davidii, not to be confused with native butterfly weed, Ascelepias tuberosa) is an invasive species in the Pacific Northwest but is not problematic here. There are, however, several popular plant species that, while beautiful, present a threat to native plant and animal life in North Carolina.

Here are a few of the most problematic invaders.

Japanese Honeysuckle Lonicera japonica

An evergreen to semi-evergreen vine with fragrant flowers, Japanese honeysuckle is often confused with native coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). Unlike coral honeysuckle, this invasive vine can kill shrubs and young trees by wrapping tightly around trunks and stems, cutting off water flow.

Japanese honeysuckle can gradually kill large trees and understory plants by blocking sunlight from reaching their leaves. It is suspected to have the highest rate of spread among invasive plants in North Carolina, multiplying above-ground via horizontal and vertical runners and below-ground with rhizomes as well as by berries dispersed by birds and small animals.

It’s extremely difficult to remove. Cutting stimulates dense regrowth, so while repeated manual pulling may eradicate small patches, well-timed application of herbicide is the only method of control known to be effective on large, well-established stands.

Multiflora Rose/Hedge Rose Rosa multiflora

Though it provides months of color with fragrant, white to pale pink flowers in early summer and tiny red fruit from summer to winter, this thorny shrub forms impenetrable thickets that crowd out native vegetation.

Once encouraged by the U.S. Soil Conservation Service for erosion control and natural livestock fencing, multiflora rose thrives in a variety of conditions and is found throughout North Carolina, reproducing by rooting the tips of arching branches and by producing up to a million seeds a year, which are dispersed by birds.

When small, these shrubs can be dug out by hand. Larger plants can by pulled out with a truck or tractor, and careful herbicide application is effective.

Chinese Privet Ligustrum sinense

An evergreen shrub that grows up to 15 feet, Chinese privet was introduced in the U.S. as an ornamental garden and hedge plant and quickly escaped from cultivation. It threatens both wetland and woodlands in North Carolina, outcompeting native species for sunlight and nutrients.

Chinese privet matures quickly, reproduces by root sprouts and by seeds spread by birds, and is very difficult to eradicate once established. Seedlings can be pulled by hand, and aggressive mowing can tame but not eliminate more mature plants. Targeted application of herbicides during cooler weather when native plants are dormant may kill Chinese privet, but the application should be repeated the next year and the area monitored closely for root suckers.

English Ivy Hedera helix

Likely brought to the Americas by European immigrants as an ornamental vine, English ivy remains available for purchase as a low-maintenance ground cover. Once established, English ivy is extremely hardy in North Carolina and has escaped

cultivation, establishing itself in nearly every imaginable landscape, including woodlands, coastal areas, forests, wetlands, and abandoned structures in rural, urban, and suburban areas.

The ivy spreads by fruit dispersed by birds, by extending along the ground, and by climbing any available surface. English ivy starves and kills large trees as well as small ones by engulfing branches and depriving the tree’s leaves of sunlight. The added weight of the ivy on these weakened trees makes them more likely to fall in a hurricane. On the ground, the dense growth of this invasive plant shades out low-growing native species.

Small patches growing on the ground can be managed with persistent hand-pulling and mulching. To remove vines from trees, cut a section of the vine out near the ground. Paint both exposed ends with an herbicide to prevent resprouting and leave the vines in place to die before peeling them off the trunk. Pulling the vines immediately can break off chunks of tree bark, causing additional damage to the tree.

Large infestations may require foliar applications of chemical herbicides, which should be carried out during fall and

winter when native plants are dormant.

Tree of Heaven Ailanthus altissima

They would be almost magical if they were not so pernicious. Seeds encased in pink, papery wings ride the wind and glide far away from the mother tree, helping Tree of Heaven invade new territory quickly. It thrives where other plants struggle, taking root despite poor soil and air quality, displacing native species, and growing over 80 feet high.

Tree of Heaven secretes an allelopathic chemical into the soil that kills surrounding vegetation and prevents other plants from growing. Young seedlings can be pulled up by hand when the soil is moist, but trees larger than half an inch in diameter will require targeted herbicide application.

Beach Vitex Vitex rotundifolia

Introduced for coastal erosion control in South Carolina in the 1980s, beach vitex is ranked the highest threat among invasive species in North Carolina because of its devastating impact on sensitive ecosystems.

Forming a monoculture on the sandy landscapes of beaches, it creates a deep shade with which native species cannot compete and produces an allelopathic chemical that suppresses or even kills native species. Sea oats and seabeach amaranth are both threatened by this invasive plant from the mint family, and beach vitex may also contribute to the decline in sea turtle nesting rates by degrading the nesting habitat with tangles of vegetation and wiry roots.

Herbicides can be carefully applied to cut stumps, and small plants can be pulled by hand, if the entire plant is removed to prevent fragments from reestablishing themselves. Because beach vitex grows in sensitive coastal environments, residents should consult the local Division of Coastal Management office before taking mitigation measures, and native species should be reintroduced to prevent erosion.

Nandina Nandina domestica

Also known as heavenly bamboo, nandina is a popular landscaping choice because of its red berries and evergreen or semi-evergreen leaves. Nandina has escaped landscaped environments and become invasive throughout North Carolina. Shade tolerant and readily reseeding, nandina forms dense thickets in a variety of growing conditions, actively displacing native plants.

It spreads by suckers and by fruit, which is especially attractive to birds during winter months when other food sources are scarce. Unfortunately, nandina has been implicated in the poisoning of some birds, specifically cedar waxwings. Its berries contain cyanide, which the birds’ digestive system cannot tolerate in large amounts.

If removed manually, root remnants may resprout and should be monitored. If removal is not possible, berry-laden branches can be pruned to prevent both reseeding and poisoning of wildlife.

Japanese and Chinese Wisteria Wisteria floribunda and Wisteria sinensis

Introduced separately in the early 1800s, Japanese and Chinese wisteria varieties were both intended as ornamentals, growing quickly and covering arbors, porches and gazebos with their cascading clusters of purple blossoms. Having escaped landscaped areas, these invasive vines are considered a threat to native plants in multiple states around the Southeast and have invaded forests, woodlands and riparian areas, as well as rural, urban and suburban landscapes.

This long-lived perennial often survives for 50 years or more, and though it sometimes produces seeds, wisteria primarily spreads by sending out runners along the ground, which take root and develop new plants at the nodes. The woody vines of invasive wisterias tightly encircle trunks and branches, girdling and eventually killing even large, mature trees. Once dense wisteria thickets are formed, native plant species are starved of sunlight and struggle to survive and are displaced.

A combination of removal methods including pulling, cutting and targeted herbicide application is recommended to eradicate wisteria.

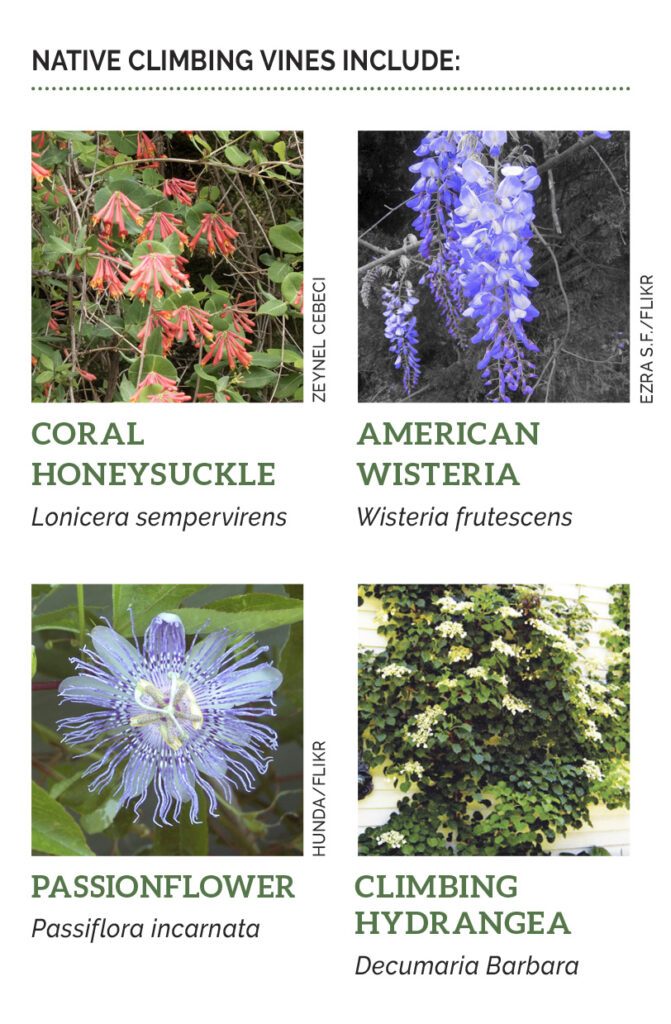

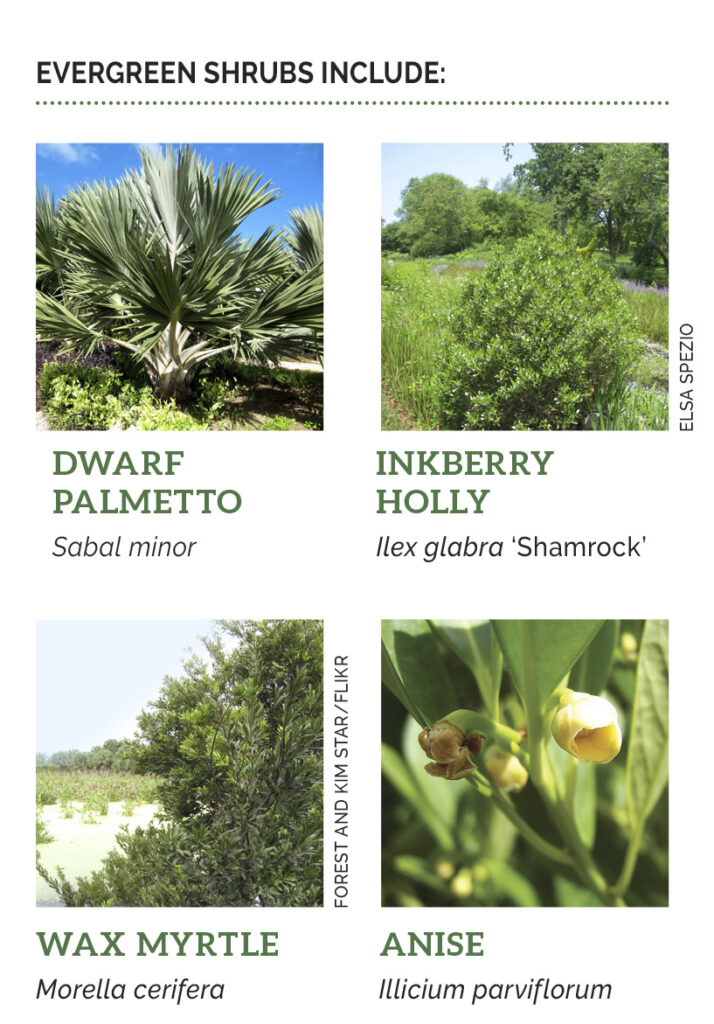

What to plant instead of invasive species

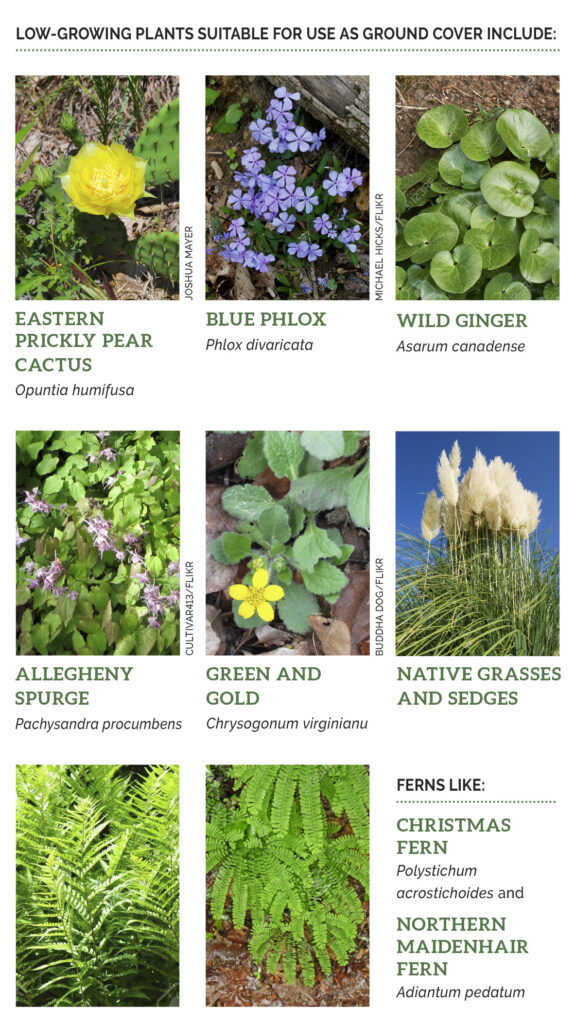

The Cape Fear region has many native plants perfectly adapted for local soil and weather conditions and that play important roles in the local ecosystem. They require little maintenance once established, so replacing invasive plants with native vegetation is a win for the gardener and the environment.

These lists of invasive species and native replacements are far from exhaustive, so consult county extension centers like the New Hanover County Extension Service Arboretum for plant recommendations and advice on reclaiming your garden.