What Lies Beneath

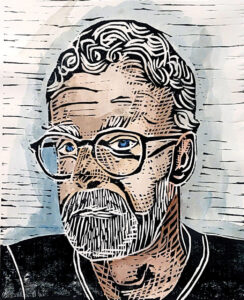

Artist Reid Coyner not only chisels away at wood to create art, but also within himself to discover who he was always meant to be

BY Emory Rakestraw

Humans are like oceans. We reveal small depths on the surface, but much more is uncovered when diving in, some never before uncovered.

Like secrets and sea creatures that linger beneath, chiseling away at a woodblock to create art also exposes. For artist Reid Coyner, the intertwining of perceived, imaginary and personal depth has been uncovered layer by layer over the years.

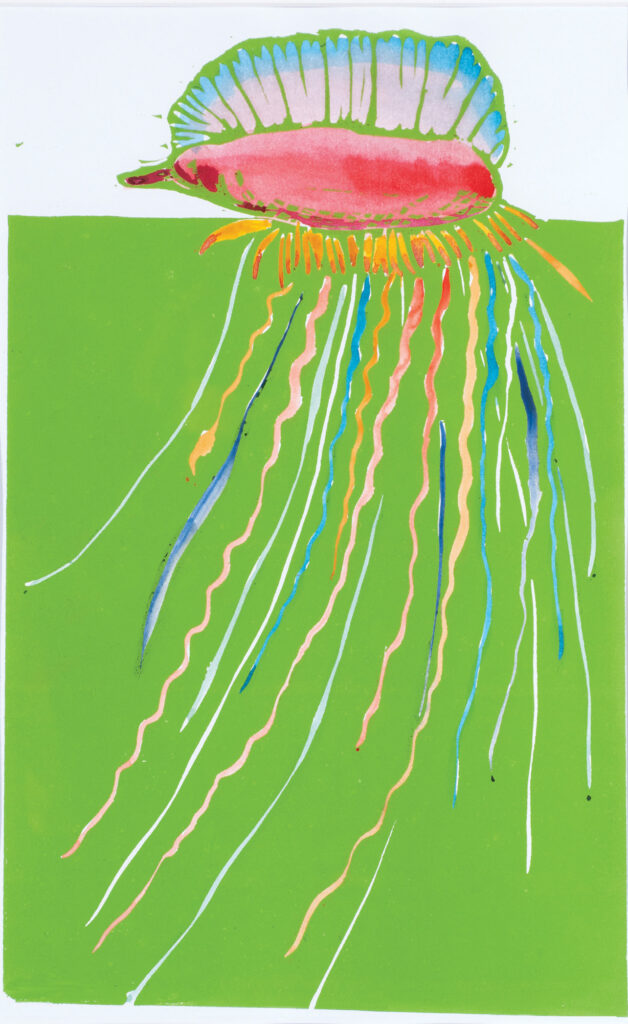

Growing up in Atlantic Beach helped spawn his early fascination with the ocean. Today, many of his prints revolve around sea creatures or swimming, the magic of the ocean and what might await, the imaginary worlds we create when we’re not able to see or venture to the bottom.

“Water meant freedom — freedom to not be two-dimensional earthbound but being able to move freely in all directions. I have always loved the way water affects the way things are seen,” he says. “The optical warping from wave motions, the watery depth perception. To me, the interest was the relationship between objects and water.”

Many of his works examine that relationship. What Lies Beneath features a goggle-wearing swimmer bubbling up to the surface as fish swirl about. The swimmer only takes up a fourth of the total piece, with a large portion dictated by the mesmerizing flow of water and how those components mingle. There is a sense of mystery and surprise. There’s also growth within movement. The swimmer seems stunted among the main subjects and their freedom to float about.

Coyner grew up in a strict household. While today he is relearning and reinventing his inner child, he had a hidden love for art and created his first piece at age 3.

“[My brother] brought home a linoleum woodblock and some cutters,” he says. “He was working and working. Mom kept saying, ‘You’ll figure it out.’ I snatched it from him, and I did it. I cut my first block at the age of 3, and I still have the block.”

He was told art and music weren’t acceptable focuses of study. Later at university, he studied design to appease his parents.

“School constantly said design is not art and has no art involved,” he says. “If I was working in the studio on a watercolor or something not assigned, the teacher would often rip it up if they could find it.”

A strict discipline and stricter household handicapped an acceptable experience of youth and development of artistic pursuits. He knew of his secret talent, sometimes not even having to learn the process. Like creating a design from a blank surface, this process wasn’t step-by-step, it was natural. Being self-taught was sometimes a study in reverse engineering. He would be able to duplicate the outcome then later learn the steps that created it.

“Being born and educated before the personal computer, digital camera, and pretty much the commercially available photocopier, I am concerned with telling my own visual story, developing my own visual vocabulary,” he says. “What I am doing is telling my own story, my own warped and fun visions of what I see or want to see. Painting and printmaking are both telling the fabrication of dimension and space. In reality, it is just flat marks on paper. We have the story of light and dark, cut and skip, and of course color; these are our tools. In the purist form, art is an abstraction from the real world and not a 1:1 duplication or clone.”

Woodblock printing is the oldest form of printmaking, widely used in Asia and dating back to the 5th century.

Coyner’s first encounter with the art form was as a child visiting the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. An exhibit of Japanese woodblock cuts instilled his love of the craft. While he began by trying to duplicate what he saw, he now has his own process streamlined.

“I grab a brush and ink to begin my woodcuts; sometimes I draw directly on the block, other times on paper. When I am happy with what I have done, I will transfer to the wood with carbon paper and a ballpoint pen. In between these two stages can be many a layer of tracing paper and many miles of ink drawings,” he says. “Cutting is simple for me, I start with a piece of hardwood (poplar or maple) or plywood and two-to-three-gauge chisels and cut.”

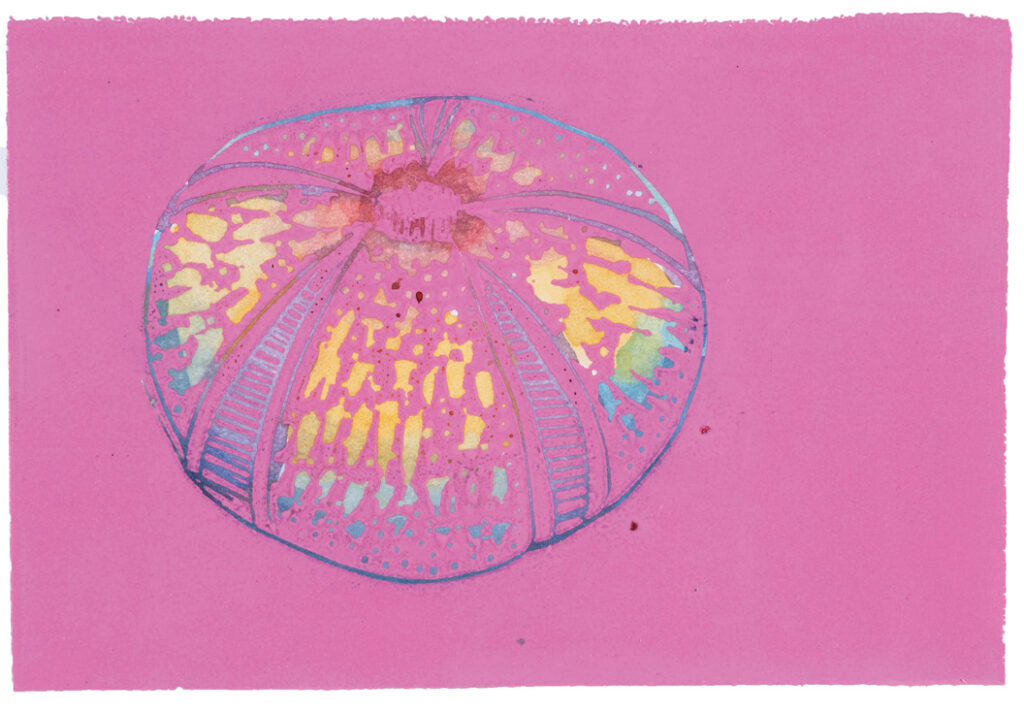

He later goes over the transferred print with watercolor, adding shape and rhythm with pastels or bright pops of color. The flow in this technique adds a personal touch to the entire process that, he notes, can take anywhere from 45 minutes to an entire day.

“I’ll cut the block, then I will start printing the block,” he says. “I use high-quality archival paper and oil-based ink and colors; with that, I can get very fine detail and color. That gives me the luxury of taking watercolor to do the oil and water thing and have some fun with paint on top of the wood paint.”

Pieces like Starfish, Urchin and Whelk display singular objects with the focus emulated in color choice. Seagull shows more apparent wood detail achieved from using various tools and specific wood grain. From singular to imaginary, Wacky Fish takes the water world elements and mixes them into a circus-like environment with a buffet of various ocean creatures placed among their own hierarchy.

His current projects relay that more playful manner, focusing on the designated “adult swim” times he remembers from his childhood at the pool. These include drink-toting swimmers floating about without a care in the world.

Much like the carefree swimmers or fish immersed among a lone subject, he’s had to find that freedom to float within himself and life in general. While a regimented childhood attempted to stunt a burgeoning artist, at almost 60 he is taking back his time.

When he’s not teaching printmaking, his days are spent on his farm with his two dogs. Fresh fruit and vegetables picked from the garden dictate the subject of the day’s artwork, then later become dinner. His timeline is now based around the dogs and their needs, or his. He is allowed to let inspiration strike when it may, even at 3 a.m.

While the printmaking process is intensive, with much skill and various disciplines required, it’s not so different from how he has had to view his own life and development. The reflecting back, the creating in opposite for acceptable transfer, is much like his approach now.

Coyner is a reverse engineer discovering many years later the inner child that lies beneath, not only in his work and creation but within himself.

I think he slso designed fabrics for textile company years ago

What a refreshing take on a truly original artist,