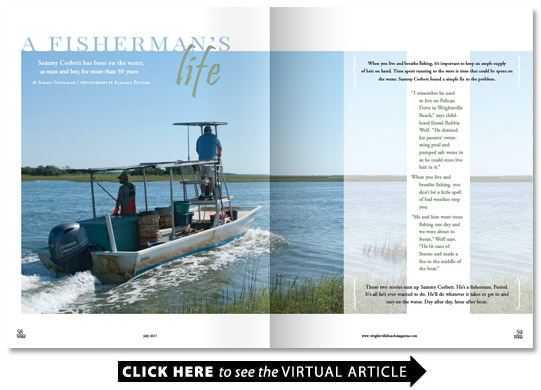

A Fisherman’s Life

BY Simon Gonzalez

When you live and breathe fishing it’s important to keep an ample supply of bait on hand. Time spent running to the store is time that could be spent on the water. Sammy Corbett found a simple fix to the problem.

“I remember he used to live on Pelican Drive in Wrightsville Beach ” says childhood friend Robbie Wolf. “He drained his parents’ swimming pool and pumped salt water in so he could store live bait in it.”

When you live and breathe fishing you don’t let a little spell of bad weather stop you.

“Me and him went trout fishing one day and we were about to freeze ” Wolf says. “He lit cans of Sterno and made a fire in the middle of the boat.”

Those two stories sum up Sammy Corbett. He’s a fisherman. Period.

It’s all he’s ever wanted to do. He’ll do whatever it takes to get to and stay on the water. Day after day hour after hour.

“I started fishing with my granddaddy [Joe Batton] when I was about 5 ” he says. “He had two girls and he always wanted a son to take fishing. So as soon as I was old enough to get in the boat I was in the boat. My granddaddy loved it. He got me started and it just kind of stuck.”

It stuck so well that Corbett became a legend among local watermen.

“Sammy tells exactly what we’re going to catch and we do ” says Wolf now a charter boat captain operating out of the dock next to the Bridge Tender. “I don’t know how he does it.”

Corbett started fishing commercially while still in junior high when his father gave him a boat. He helped run Wolf’s charter boat while in high school. He’s fished for grouper so successfully his method was outlawed. He helped perfect a way to fish for sharks until that too was banned. He’s fished offshore and in the sound for spots croakers mullets crabs — just about anything.

“Years ago he was an offshore fisherman and a pioneer in a style of grouper fishing a lot of people do now ” says charter boat captain Ger Hardin. “They used to use big heavy gear on boats that stayed out for days. He pioneered smaller boats. That was a big change in the industry.”

Corbett has spent his long professional career operating boats both big and small and using just about every conceivable method to catch seafood. He’s learned a thing or two in all those years. So much so that it’s easier to make a living now.

“I would like to think it’s because I’m a little bit smarter than I was then but there are people who would say that’s not true ” he says with a chuckle. “I know more about when to go and for what now. I know what to look for by the weather by the temperature. It makes it easier. The amount of money I take home after I pay my expenses is a lot more now.”

He’s always willing to pass along what he knows along with sharing a fish story or two with just about anyone.

“He’s the most down-to-earth nice fellow you’ll meet ” Hardin says. “The amount of knowledge he’s got you’d think he’d have a different personality. He doesn’t hold his nose in the air.”

He’s on the water every day unless he has to go to a meeting. His expertise — and his reputation — led to an appointment three years ago as chairman of the North Carolina Marine Fisheries Commission.

The commission works under the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries which is responsible for the state’s marine and estuary resources. Corbett and the eight other commissioners help establish policies that regulate commercial and recreational fisheries.

Corbett had sat on other such boards to learn what he could and look out for the rights of commercial fishermen.

“Somewhere around ’96 I started getting involved with the fisheries committees sitting on the Southern Regional Advisory Committee and whatever committees I could get them to put me on ” he says. “The federal fisheries were getting more and more shut down by that time. The guys could hardly make a living grouper fishing because they had such short seasons put on them and I kind of wanted to make sure the inshore fishery I was doing would last that I would keep going with it.”

He had been approached about serving on the Marine Fisheries Commission but had always said no.

“They keep trying to get me ” he says. “Louis Daniel who was the director of Marine Fisheries for quite a while up until recently he kept trying to get me on the commission. And then about three years ago I had a weak moment and said yes. The governor put me on there and that’s been more than I ever bargained for.”

Any storms he faced while at sea were nothing compared to what he’s experienced serving on the commission. He’s frequently caught up in the battles between two warring factions: commercial fisherman who want fewer restrictions so they can make a living and recreational fishermen who favor restrictions on their commercial counterparts so there are more fish for them.

“They fight about anything ” Corbett says. “They don’t want to get along. They want to come in and blame other people.”

As someone who makes his living from the water Corbett is perceived as one always on the side of the commercial fishermen.

“A lot of people don’t want to talk to him because they think he sides with commercial ” Wolf says.

But Wolf — admittedly a biased source — says Corbett is fair to both sides.

“He calls me when there’s an issue or whatever to get my take ” Wolf says. “He calls around and talks to people. Not just in the commercial sector either. I think he’s doing one heck of a job. You are always going to have that tension. A lot of the recreational fishermen want to blame their lack of knowledge and success on the commercial fishermen. The ones that yell the loudest are the ones who know the least.”

Corbett has a simple measuring stick to gauge his fairness.

“If they look at how many people dislike me on either side they might think I’m pretty fair ” he says. “I think I have an equal amount that don’t like me on both sides.”

Corbett sees himself as representing the needs of the consumer.

“If you take away the commercial fishing industry the people in the state of North Carolina are the ones that are the losers ” Corbett says. “Those people are going to lose their fresh local seafood. We’ve had a group that have started coming to the meetings that say we don’t fish but we love to eat fish and we’re here to make it so we can eat fish that we know where they come from.”

Corbett’s term is up at the end of June. During a conversation in May he didn’t know if he would be reappointed. He was first appointed by a Republican Pat McCrory and the incumbent Roy Cooper is a Democrat.

“We’ll see ” he says. “If they look back and think I was doing a decent job they may keep me. Or they may not.”

Despite the headaches he’s willing to keep serving.

“It may be frustrating but right now I’ve got a front-row seat to try and do the battling ” he says. “I’ve got a little bit of knowledge about what’s going on. I would stay. My wife might not like it but I would.”

It’s a no-lose scenario. If he stays he can keep battling. And if he goes he’ll have more time to spend on the water. Just as he’s been doing since his dad bought him that first boat more than 40 years ago.

“When I was about 13 years old my daddy bought me an Allendale well boat which back then was the thing ” Corbett says. “He said ‘No more allowance. There’s two gill nets on there and there’s an oyster knocker and a clam rake. Take your fish to Mr. Hines and that’s your allowance.’ In the seventh or eighth grade I’d come home from school and not do my homework and go fishing.”

Mr. Hines was L.T. Hines who ran Hines Seafood on Wrightsville Beach. He not only would buy whatever Corbett caught but also employed the young man.

“We lived on Seacrest behind where the market was ” Corbett says. “I worked there many a day. Stinky Williamson was the chief of police. Stinky wrote me a note. Mr. Hines had an ugly green Datsun truck. We set minnow traps beside Wrightsville Beach School for our live bait. At 13 years old I could get in that little Datsun truck and I could drive it from his market to Wrightsville Beach school and pick up those minnow traps and come back. I could drive on Wrightsville Beach as long as I was just going to pick up minnow traps. Of course there weren’t many people on Wrightsville Beach back then.”

In high school he started fishing with Robbie Wolf and his brother Ed.

“Robbie’s dad bought the Whipsaw and all of a sudden we were fishing every weekend and learning all about it ” he says. “Probably the best times I had fishing ever were back in the late ’70s when Robbie and Ed and I were fishing together. They were family and we just had a ball.”

After high school the Wolfs decided to go into the charter business. Corbett wanted to go solo as a commercial fisherman. Atlantic Marine owner Mike Merritt the Corbetts’ next-door neighbor on Pelican Drive helped him get his first boat.

“He basically got me started by helping me get a boat to start with ” Corbett says. “A lot of good people at Wrightsville Beach helped me to get going.”

Corbett set out to become a grouper fisherman in part because he and the Wolfs had figured out where to catch them.

“We had always trolled and anytime we wanted to catch a grouper for somebody we’d slow down and let the trolling line sink. When we’d speed up we’d catch grouper ” he says. “It was close to shore 8-10 miles 12 miles and nobody grouper fished in there. The grouper boats went 50-60 miles out. Just like I thought there was plenty of fish there. So we started grouper fishing.”

When hook-and-line methods didn’t bring in enough fish he tried something else. Corbett devised a trap that he baited with a jar full of mud minnows.

“I would put that gallon pickle jar so it looked like a school of fish in there ” he says. “The groupers couldn’t stand that. They went right in there to it. It was like an oversized crab pot except it had one entrance way in it. It was about the size of the bed of a pickup truck. It worked good.”

Even then Corbett wanted to make sure he was doing things by the book. He invited officials to see what he was doing.

“Anytime you do something like that and the feds get wind of it they’re going to send people to come out and see what you are doing. They are very curious ” he says. “So I took observers and it wasn’t long after that they closed it.”

He had heard rumors of people long-line fishing for sharks so he tried that next selling the meat to Hieronymus Brothers Seafood on Airlie Road.

“It wasn’t long before a bunch of people started getting into it ” he says. “We might have done it for two years before they stopped us. They stopped us because there was a bunch of the bigger boats that came from the Gulf and they weren’t selling the meat. They were finnin’ sharks. We got grouped right in with those guys. We were selling everything. We would cut the jaws out and sell them to the local shops here on the beach. We sold the meat and we sold the fins. There was nothing that went to waste. But the big boats they weren’t interested in anything but fins because they were big money.”

Back surgery in the ’90s put an end to grouper and most offshore fishing. Now at age 57 he prefers to stay close to the shore gill netting for roe mullet and crabbing.

“I very rarely go past the sea buoy anymore ” he says. “In spot season I may go in the ocean 40 or 50 foot. My business now is pretty much crabbing and I do love to roe mullet fish.”

Corbett is sometimes asked if he regrets never going to college. The answer is a quick no.

“I’ve enjoyed every minute of it ” he says. “I really have. I couldn’t have had no more fun.”