Yuletide Treats

BY Colleen Thompson

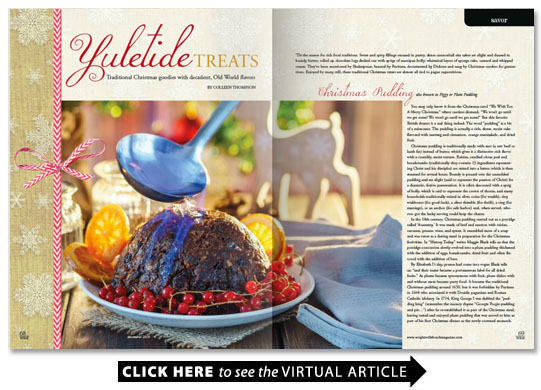

Christmas Pudding also known as Figgy or Plum Pudding

You may only know it from the Christmas carol “We Wish You A Merry Christmas ” where carolers demand “We won’t go until we get some! We won’t go until we get some!” But this favorite British dessert is a real thing indeed. The word “pudding” is a bit of a misnomer. The pudding is actually a rich dense moist cake flavored with nutmeg and cinnamon orange marmalade and dried fruit.

Christmas pudding is traditionally made with suet (a raw beef or lamb fat) instead of butter which gives it a distinctive rich flavor with a crumbly moist texture. Raisins candied citrus peel and breadcrumbs (traditionally they contain 13 ingredients representing Christ and his disciples) are mixed into a batter which is then steamed for several hours. Brandy is poured over the unmolded pudding and set alight (said to represent the passion of Christ) for a dramatic festive presentation. It is often decorated with a sprig of holly which is said to represent the crown of thorns and many households traditionally mixed in silver coins (for wealth) tiny wishbones (for good luck) a silver thimble (for thrift) a ring (for marriage) or an anchor (for safe harbor) and when served whoever got the lucky serving could keep the charm.

In the 14th century Christmas pudding started out as a porridge called ‘frumenty.’ It was made of beef and mutton with raisins currants prunes wine and spices. It resembled more of a soup and was eaten as a fasting meal in preparation for the Christmas festivities. In “History Today ” writer Maggie Black tells us that the porridge concoction slowly evolved into a plum pudding thickened with the addition of eggs breadcrumbs dried fruit and often flavored with the addition of beer.

By Elizabeth I’s day prunes had come into vogue Black tells us “and their name became a portmanteau label for all dried fruits.” As plums became synonymous with fruit plum dishes with and without meat became party food. It became the traditional Christmas pudding around 1650 but it was forbidden by Puritans in 1664 who associated it with Druidic paganism and Roman Catholic idolatry. In 1714 King George I was dubbed the “pudding king” (remember the nursery rhyme “Georgie Porgie pudding and pie�”) after he re-established it as part of the Christmas meal having tasted and enjoyed plum pudding that was served to him as part of his first Christmas dinner as the newly crowned monarch.

Mince Pies

We know them as spicy little mouthfuls seasoned with cloves cinnamon and nutmeg plumped with brandy and encased in crumbly pastry that makes an appearance at Christmastime. But these pies have a long history often steeped in legend. They have been transformed from mounds of lard and mutton to tasty elegant tarts. According to author Janet Clark author of “Pie: A History ” pies were initially just meant to be containers that would act as vessels to keep meat preserved in fat. Spicy meat pies have been relished in England ever since the Crusaders brought spices back from the Middle East in the 12th century.

In the English cookbook “A Forme of Cury” — originally written on a scroll documenting a compendium of medieval recipes — contains a recipe from 1390 for a pie of meat and spices. They were called “Tartes of Flesh” and ingredients included ground pork hard-boiled eggs spices of saffron and sugar. Ingredients like honey and dried fruit were expensive in medieval times and the combination of these were only ever for the rich who used them to show off social status.

Originally oval mince pies were meant to represent the manger and were often decorated with dough figures of the baby Jesus. By the end of the 17th century they were turned into the familiar round shapes as religious depictions started to be frowned upon by Puritans. Exactly when meat was left out of mince pies is up for debate. Eliza Acton’s mincemeat recipe in ‘Modern Cookery for Private Families’ (1845) includes ox tongue and ‘Mrs. Beeton’s Household Management’ (1861) gave us two recipes for mincemeat one with and one without meat.

Suffice it to say that the eponymous meat pie was meat free by the 20th century but the superstition of eating a mince pie each day between Christmas and Twelfth Night to bring luck and happiness remained.

Trifle

Second only to the traditionalChristmas pudding is the classic British trifle making an appearance on Boxing Day and again on New Year’s Eve.

The word “trifle” — pronounced Tri-fuhl — according to “What’s Cooking America ” comes from the old French term “trufle ” meaning something whimsical or of little consequence. They also tell us that a proper English trifle is made with real egg custard which is poured over sponge cake or finger biscuits which have been soaked in fruit and sherry and topped off with whipped cream.

Many puddings originated as a way of using up stale leftovers of bread and cake and trifle originated much the same way as the Italian “Zuppa Ingles” (English Soup) or the Spanish dessert called “Bizcocho Borracho.”

The first mention of ‘triel’ was a thickened spiced cream at the end of the 16th century. As early as 1598 the translator John Florio referred to ”A kinde of clouted creame called a foole or a trifle in English.” Trifle has changed over the centuries both in appearance ingredients and taste. Trifle in the Tudor period combines cream and rosewater flavored with ginger spices and sugar. By the 18th century there were recipes for macaroons and sponge fingers soaked in sack (a white fortified wine) and covered with jelly custard and flowers. It was during the Victorian era that trifle soared in popularity.

There is no classic trifle recipe or rules that constitute a “real” trifle. There is no consensus as to canned fruit fresh fruit or no fruit at all. Some (like me) only use strawberry jam instead of fruit. Many people do a layer of sponge or finger biscuits then a layer of custard and a layer of whipped cream and repeat the process.

Fruit Cake

It is the most British of baked goods — and the punch line of many holiday jokes. However when done right the much maligned iconic Christmas cake is delicious. As with all good things fruitcake takes time and should be made at least one month in advance of serving. This allows the cake to deepen its flavors because the fruit contains tannins that are released over time.Its longevity lasting for months without going bad is due to its moisture-stabilizing properties mainly sugar.The high density of sugar reduces the cake’s water content and therefore its ability to bind to bacteria.

History and lore are intertwined when it comes to fruitcake. Ancient Egyptians placed versions of fruitcake on the tombs of loved ones as food for the afterlife while an ancient Roman recipe consisting of pomegranate seeds pine nuts raisins and barley mash seems to be the oldest.

Around the Middle Ages honey fruit and spices were added to the cake. Crusaders were reported to have carried cakes of embalmed fruit to sustain them on long journeys. It was during this time that the name “fruitcake” was first used. By the 1400s the cakes became heavier and more laden with dried fruit imported from the Mediterranean to Britain. Originally raised with yeast by the 1700s the loaves were raised with eggs.

There are various theories about how fruitcake became tied to the holiday season. Some believe it was because English citizens passed out fruitcake slices to the poor women who sang Christmas carols on the streets of London in the late 1700s.

Yule Log

The Yule log cake (or the French b�che de No�l) is a rolled chocolate sponge cake filled with cream and frosted with chocolate buttercream icing and elaborately decorated to look like bark with marzipan mushrooms holly sprigs spun sugar cobwebs and all sorts of edible festoons.

The superstition of burning a Yule Log dates to a Nordic custom from medieval times — Yule was the name of the old Winter Solstice festivals held in Scandinavia. A large log was placed in the fireplace after being sprinkled with oil or wine as an offering and then burned on Christmas Eve and through the 12 days of Christmas. The wood the log itself and who placed it in the fireplace were all of great importance as it was erroneously believed the ritual offered magical protection to the home and all those who lived there.

With time traditional hearths disappeared in homes and were replaced by wood-burning stoves. Smaller logs placed on tabletops as decoration replaced the wood-burning version and eventually the Yule tradition turned into an edible version of a rolled chocolate log.