Whale Trouble

BY Daniel Bowden

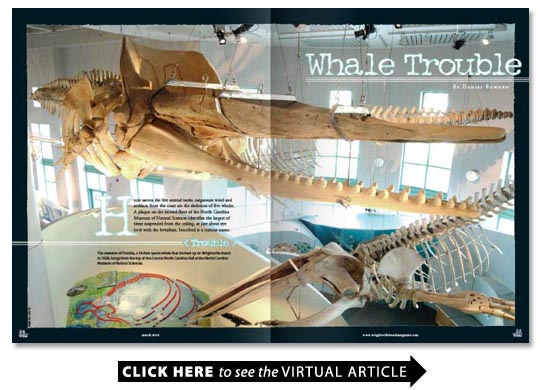

High above the live animal tanks sargassum weed and artifacts from the coast are the skeletons of five whales. A plaque on the second floor of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences identifies the largest of these suspended from the ceiling at just about eye level with the leviathan. Inscribed is a curious name: Trouble.

The Morning Trouble Washed Ashore

It is the morning of April 5 1928. An agent of the Clyde Steamship Company and year-round resident of Wrightsville Beach M.M. Rileyresides in a cottage along the now-underwater beachfront strip called Ocean Avenue. Riley prefers to start his day with a walk along the shores of the Atlantic and this morning begins no differently. However as he walks out the door he spots the waves lapping around a tremendous shape.

The creature in the surf will later measure 54 feet and 2 inches long and 33 feet in girth. It is a 100 000-pound male sperm whale speculated to have died from a whalers harpoon.

Whaling was once a flourishing industry off the Carolina coast but overzealous whalers quickly worked themselves out of a job. The last whale reported killed by North Carolina whalers was taken off the coast of Carteret County in 1913; however fleets from New England occasionally dipped south in the years that followed.

Word of the dead sea creature spreads quickly into the town and beyond. Before long traffic on the newly constructed causeway bridge is jammed up bumper to bumper. Tide Water Power Companys electric railway does rush business transporting passengers to the beach. An April 10 edition of the Morning Star reports that 50 000 visitors from at least six states have come to see the behemoth.

Initially Wrightsville Beach Mayor George Kidder is pleased with all of the attention the whale has brought his little beach town. But the excitement fades in a few days time as the increasingly putrid smell emitted by the rotting carcass begins to deter the once-eager visitors. Before long Kidder realizes he has a serious problem on his hands.

In his book Land of the Golden River Philip Seymour Hall recalls public health officials in an uproar with one such Dr. John Hamilton threatening to throw the book at Wrightsville Beach officials if something isnt done immediately.

H.H. Brimley

Herbert Hutchinson or H.H. Brimley is 67 years old and has been the director of the state museum of natural sciences in Raleigh for 30 years when he receives word of the situation at Wrightsville Beach. Brimley immediately recognizes the potential value of such a specimen and sends his assistant Harry Davis to Wrightsville Beach.

Through correspondence with other American museums Brimley later learns his instincts were correct. In 1928 only four other museums in the country have sperm whale skeletons and this particular whales bones are estimated to be worth approximately $1 800. (The United States Bureau of Labors Consumer Price Index estimates that is the equivalent of $24 170 today.)

Upon arriving in Wrightsville Beach and seeing the whale Davis writes that he does believe this will be the largest sperm whale skeleton in America and estimates that it will take about a week to remove the flesh and bury the bones in the sand a process used to clean them. Local health officials are not pleased with that timeframe and order Kidder to dispose of the whale immediately. Their solution is to tow the whale 20 miles out to sea and set it adrift.

Fortunately for Brimley the first attempt at towing the whale fails the next day and a strong storm blows in deterring towing efforts for several more days. Brimley recognizes this opportunity and calls the towing company seeking to change its instructions. Instead of towing the whale 20 miles out to sea and setting it adrift Brimley asks if it would tow the whale 20 miles north and cut it loose just off the coast of Topsail Island which is largely uninhabited at the time. The towing company agrees.

When the seas calm and the towing company returns three days later the lower jaw removed by Davis is missing. Some speculate it was lost to the sea or buried in the sand during the storms but documents available from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences indicate that others suspect foul play stating a sperm whales teeth are ivory. The full set attached to the whales lower jaw could fetch a sizable sum.

This second towing effort is a success but the towing company overshoots the target drop-off point by about a mile. Captain Ramp Smith a Topsail fisherman hired by Brimley to bring the whale to shore finds himself in over his head in his attempts to do so. Fortunately Capt. Smith is spotted by the crew of a U.S. Coast Guard cutter that witness the odd goings-on and suspect him of towing an illegal rum cach. Upon clarification of the situation the crew helps deliver the whale to shore.

Trouble in Topsail

The whale is anchored on the property of TheodoreEmpie a friend of Brimleys who owns a two-mile stretch of desolate beach on Topsail Island. Over the next few weeks Davis and a crew of local fishermen process the whale hacking away its flesh with broad axes and spades and burying the bones in the sand.

Although one would think that with the whalebones buried the trouble would finally subside but it doesnt. Topsail residents spend the next six months scheming ways to make money off of the whale. Some claim they can produce the missing lower jaw for a reward. Others complain about a host of health and fishing problems allegedly caused by the whales flesh in the surrounding waters.

The residents cause such a fuss that Capt. Smith hired to tow the flesh out to sea returns the money he had been paid. In a letter addressed to Harry Davis he writes that If [the whale flesh] is near Kings Landing or has been at any time it certainly came back but he returns the money Because I havent got the name of being a thief.

During this time an exasperated Brimley writes that the procuring of the whale has been a heartbreaking job from the start. It would seem that every possible obstacle many natural and some man-made has been placed in the way of our carrying out the work to a successful conclusion.

Brimley responds to the Topsail residents saying he has been unable to find any evidence of the whale flesh remaining in Topsail and that if anything its presence would improve fishing. No money is ever given to the distraught residents.

Trouble at the Museum

Six months later Davis returns to Topsail to unearth the bones and bring them to Raleigh on two flatbed trucks. The bones are processed in Raleigh for another year before they are ready to be assembled.

In the first bit of good fortune since the whale washed ashore Brimley procures the lower jaw of a similar-sized sperm whale from the American Museum of Natural History in New York and dental plaster is used to make fake teeth to fit both jaws. The complete assembly of the whale takes six weeks. About half of that time is spent on the skull which had to be broken into several pieces during the cleaning process. In February 1930 almost two full years after washing ashore Trouble hangs suspended from the ceiling.

We have made a first class job of [the whale] Brimley writes and it is attracting a great deal of attention. The museum now boasts of three large whale skeletons. A sperm whale finback whale and right whale all from the North Carolina coast.

Trouble has been moved several times since then: twice for remodeling once for cleaning and once when the museum changed buildings. Today a stylized image of Trouble the Wrightsville Beach whale has become the museums mascot. T-shirts mugs key chains and other merchandise bearing the logo can be purchased in the museum store. It appears Trouble has finally outlived its nickname.