Turning Over a New Leaf

Fiber artist and eco-printer Rebecca Yeomans enlists nature to steer the direction of her artwork

BY Emory Rakestraw

Nature’s beauty changes with the seasons. As fall approaches,leaves turn burgundy and golden. Dormant winter echoes nature at rest. New life in the spring and summer means bountiful greens.

As seasons come and go, Rebecca Yeomans views each as an artistic vessel.

“I get so excited in the spring when the leaves are starting to come out. I really like the spring greens, they’re fresh and pretty,” she says. “I like grapevine leaves, Coreopsis flowers, Catawba leaves and Japanese maples. They’re all good printers.”

By printers, Yeomans is referring to eco-printing, which involves transferring plant and flower shapes onto cloth or paper.

The first recorded botanical printing dates to ancient Greece, when physician, pharmacologist and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides used the process in a plant-identification manual. Some 1,400 years later, Leonardo Da Vinci showcased a sage leaf alongside printing instructions in one of his manuscripts.

While botanical identification with printing has ancient roots, it was solidified by fiber artist India Flint in her 2008 book Eco Colour.

Yeomans’ long love of foraging and fiber arts intertwined once she was introduced to the technique.

“In 2016, I took an intensive three-day workshop with a Wilmington fiber arts group on eco-dyeing,” she says. “It was about 10 of us, but I’m the only one still doing it. I really took to the process.”

The following year, Yeomans participated in a workshop with Flint. In a signed copy of Eco Colour, Flint wrote to Yeomans, “Dye slow and dye happy.”

Today in Yeomans’ garage workspace, cloth and leaves drape the table. Her foraged collection comes from daily walks and plants grown in her garden.

She prefers to print on silk. She starts by dipping fresh-picked leaves in an iron solution. Certain leaves like grape and oak possess more tannins, lending to dramatic, darker impressions.

Through workshops and self-education, Yeomans also developed her own natural dyes for fabric and scarves.

“Avocado pits make this really pretty pink color. I’ve got bags of them in the freezer, and it takes about 10 to make a dye,” she says. “I use onion skins and some others that include Osage orange and marigold.”

When it’s time to print, she takes her fabric of choice and soaks it in a vinegar wash, blotting until damp. Depending on the desired pattern, leaves can be placed close together or farther apart. Yeomans stresses the importance of not going into an eco-print with a predetermined design, as you never know what you might get.

“Leaves have a sun and moon side; the vein side prints dark, and you get a silhouette of the leaf,” she says while placing each on the cloth, then selecting a pole.

Wider poles are used to spread out the design; smaller ones condense the nature at hand. Some eco-printers prefer to separate sections with plastic wrap, but she loves the “ghosting” effect achieved from non-constrained imprints.

“Some of my printings contain only two leaves, but when you roll it on your pole they bleed through and form a pattern,” she says. “A lot of people put down layers of fabric or plastic to keep it from ghosting. I’m into the ghosting so all of my prints have background things going on.”

She applies as much strength as possible when rolling. Each print is birthed through a combination of moisture, heat and pressure. She binds them with plastic wrap. An alternative includes twine, which lends its own separate effect.

The fabric-adorned pole is placed in a large pot atop boiling water to steam for two hours. For flowers, she prefers 30 minutes.

Yeomans’ artwork doesn’t end with an eco-print. It’s merely part of a process combining embroidery, knitting and jewelry-making.

“Growing up, a lady down the street babysat us. She was a knitter and taught me how to knit at age 8,” Yeomans says. “By middle school I was knitting cable sweaters and entering them in the Cleveland County Fair, winning ribbons in the adult category. The fiber art started with my jewelry. When my kids left the house, I started making jewelry, knitting with tiny needles and beads on the thread. That introduced me to the fiber arts collective. We took the eco-printing class and I just moved right along.”

Her early eco-prints began with scarves. As she’s grown accustomed to the process, practicing trial-and-error by recording detailed notes on each, her artwork has evolved into a collective of handmade creations.

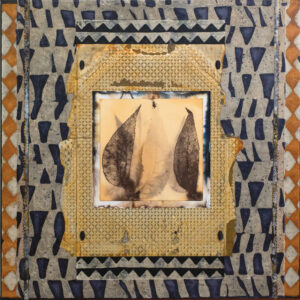

In Maple Windfall, leaves are outlined in embroidery as the ghosting technique lends to distant whispers of silhouettes in between texture. Grevillea, part of her Grid series, showcases a botanical imprint framed by painted, distressed paper. Yeomans uses toilet paper rolls and shopping bags to lend earthy and sometimes tribal aesthetics, particularly seen in Pecan from her Bag series.

A classically trained artist, her recent work combines multiple processes while evoking an educational discipline. In Still Life with Flowers and Fringe, imprinted florals are embroidered as dyed fabric forming the shape of a vase. HerBoho Bouquets enlist a similar approach, nodding to works by Henri Matisse and Raoul Dufy.

“I did a free online workshop with three different fiber artists. For one, the prompt involved doing a sketch to learn how to transfer it onto fabric,” she says. “I did a still life sketch. If you take the sketch, put it on fabric, stitch through then tear the paper away, it’s right there. I would’ve never thought of that.”

While she prefers to start with eco-prints, she hasn’t abandoned her knitting skills. The proverbial lightbulb of creation exists in her various lanterns displayed at the annual Cameron Art Museum Illumination Exhibit. Yeomans’ project for the 2022 exhibit involves knitted fabric that fittingly forms the shape of a leaf.

As she learns and perfects her craft, she’s discovering her footing as both an eco-printer and fiber artist. Even as future works involve household items or strips of wallpaper, first and foremost nature and her interpretation of its beauty take precedence.

“As a child, I was encouraged to play outside and roam free. I was an avid collector of rocks, leaves and marbles,” she says. “When I look back at my life now, that’s exactly what I’m doing,”

Beautiful work!! Love it❤️

I love Becky’s art. She is so inspiring!