The U.S. Coast Guard Mounted Patrol

A vital but little-known part of coastal North Carolina’s World War II experience

BY Robert Rehder

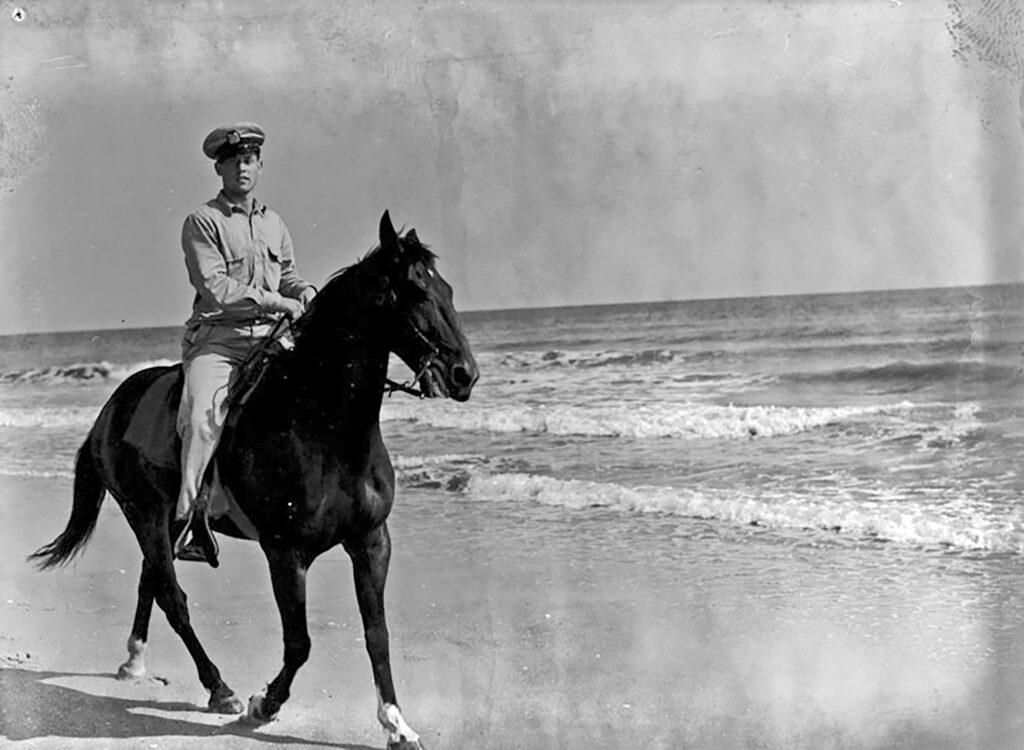

In the long and honorable service of the United States Coast Guard, there was a unique assignment during World War II. Although a maritime service, it provided armed, horseback-mounted patrols along the nation’s coasts, including North Carolina’s beaches and barrier islands.

Smith Island, now Bald Head Island, and Oak Island saw especially active patrols.

Imagine being on one of those peaceful islands for a day of swimming, fishing or beachcombing, and then seeing armed horseback riders patrolling the beaches with German shepherds, scanning the horizon and suddenly galloping toward you. That could have happened on any of our local beaches from the spring of 1942 through early 1944.

The attack at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, brought the U.S. into the war. By June of 1942, our merchant vessels — including Liberty Ships built at the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company in Wilmington — were transporting oil, supplies and troops to support the allied war effort, especially in Europe.

To stop the flow of supplies, German U-boats were dispatched to the Atlantic Coast to sink any ship in sight. The result was devastating.

German submarines hunted up and down the coast, waiting sometimes just offshore to assault merchant freighters and oil tankers. In the first eight months of 1942, more than 50 merchant ships and many lives were lost to U-boats patrolling off the North Carolina coast.

In March 1942, the tanker John D. Gill was torpedoed by U-158 25 miles east of Cape Fear near the Frying Pan Shoals. Eleven surviving crew members and security guards were rescued by the Coast Guard vessel Agassiz and taken to Southport. Later the Southport Historical Society dedicated a monument to the men and ship.

In addition to the danger to ships and crews, there was fear that U-boats would carry out sabotage and espionage missions by landing commando crews to infiltrate coastal cities. There was considerable concern about the safety of the coastline, especially along the shores of North Carolina, which was known as Torpedo Junction.

The numerous ship sinkings threatened the entire war effort, and as the German menace became increasingly alarming, the need for organized coastal security intensified. In response, the Coast Guard formed a special unit called the Coast Guard Beach Patrol.

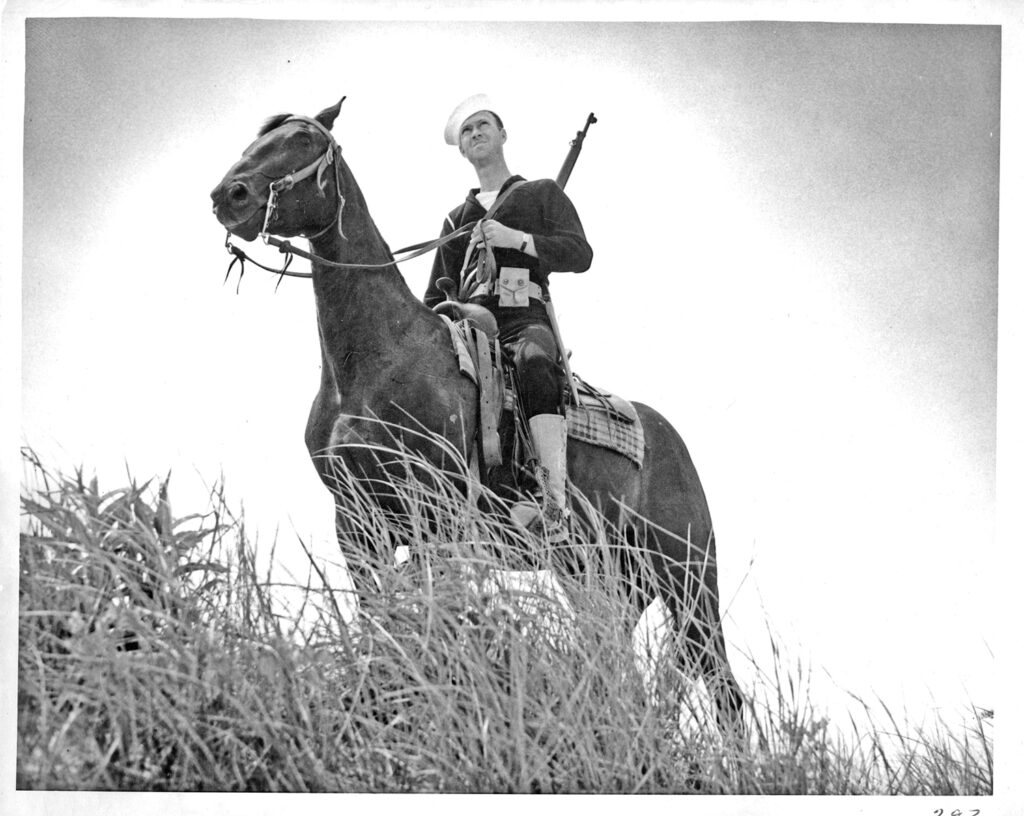

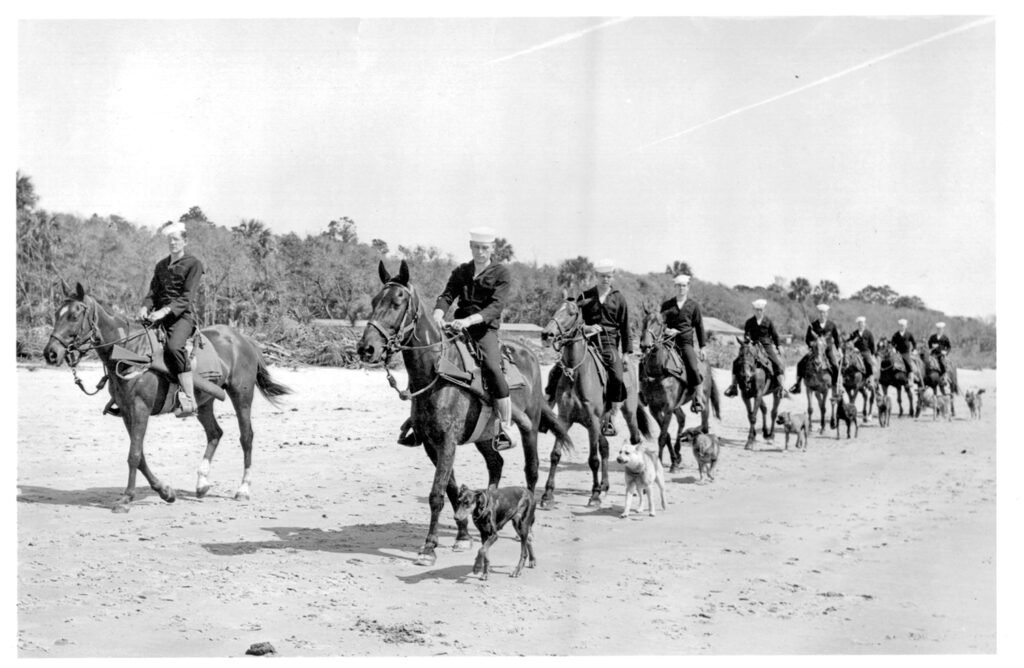

Odd as it may seem for a seagoing unit, these shore patrols were armed mounted units, accompanied by specially trained dogs. Primarily a security force, their duties included protecting against sabotage or enemy landings, detecting and observing enemy vessels, transmitting information to shore units, and preventing communication between persons ashore and the enemy at sea.

Of special interest were North Carolina beaches, which provided excellent vantage points for coastal and ocean observation and had reasonable access by land or water.

The Coast Guard advertised for men who could ride and handle horses. There was a broad response across America from cowboys, farmers, hunters, jockeys and horse trainers. Successful applicants were trained at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina.

The horses came from the Army. The Marsh Tacky, which is now the South Carolina state horse, and the Carolina Banker, the state horse of North Carolina, were two of the popular breeds. Bankers had been successfully used by the Coast Guard previously for beach watches and rescues and were well suited for work on the islands.

Both breeds developed from horses brought to the Carolinas by Spanish explorers, settlers and traders as early as the 16th century. They were used by colonists during the American Revolution and by settlers for farm work, herding cattle and hunting. Other breeds struggled in the soft, difficult terrain of swamp, mud, water and marsh of the barrier islands, but Marsh Tackies and Bankers were sure-footed, calm, and adaptable to the landscape.

Riding gear was provided by the Army Remount Service. Uniforms and other gear that included boots, heavy outerwear, radios, rifles, pistols and survival kits were provided by the Coast Guard.

The isolated beaches of Oak Island and Smith Island were especially suitable for patrols because of the wide view available and reasonable boat access. East Beach at Smith Island already had a lifesaving station with several outbuildings. On Dec. 6, 1942, it was selected as the first official mounted patrol station on the Southern coast.

In an interview for the 1995 UNCW Oral History Project, Petty Officer Cheser Hennis, a Coast Guard boatswain’s mate, recalled life at Smith Island.

“All these kids from Texas and Oklahoma thinking they were cowboys volunteered,” he said. “They were scared of the ocean and boats and wanted to get on their horses away from boats. The Mounties lived in a long-gone, board-and-batten beach shack with a screened-in porch at Bluff Island up the East Beach.”

Two months later in February 1943, a second station was opened across the river on Oak Island’s Long Beach. One man who answered the Coast Guard’s early call there was Jack Hubbard, who was raised on a farm in Cumberland County. In a conversation with his sister Barbara Hubbard Wilson, he recalled memories at Oak Island.

“Many had never ridden anything but a hobbyhorse. During training there were men so saddle sore they stood to eat their meals. Those horses from the U.S. Cavalry knew every trick in the book.”

Barbara Wilson continued, “The men built stables and corrals for the horses. With some help they built an observation tower on the big hill at the west end of the beach. Wood also had to be cut to fire up the wood stove. In his opening greeting to the new patrol, the commanding officer said the men had to survive on their own on the barrier islands and would get supplies when they could. Supplies arrived by boat usually once a month and consisted of coal for the cook stove, and hay, oats and bran mash for the horses along with a few items for the men. Sometimes the men felt the horses received the most attention.”

Conditions at both stations were poor with extreme, muggy heat in summer and wet, bone-chilling cold in the winter. Gnats, bugs, sand and wind added to the discomfort. The interior of both islands was a jungle of cedar, cypress, oak and myrtle where wild boars, foxes, alligators, raccoons, deer, snakes and biting insects roamed. Clams, oysters, fish and wild pig barbecue occasionally offered a pleasant change to their spartan menus.

Watches were maintained day and night regardless of the weather. The guardsmen mostly patrolled in pairs from two to four hours, each watch covering several miles of beachfront. They carried rifles, pistols, flashlights and radios and were usually accompanied by trained dogs that wore canvas booties to protect their feet from oyster shells.

The routine was rigorous and required strength and patience. Guardsmen did their own cooking and managed the cleanliness and upkeep of the stations. It was tough and difficult duty, but the morale of the men was high as they went about their watches and attended to the animals in their care.

The danger of enemy landings declined during the summer of 1943, and U-boat activity off the coast decreased with the introduction of radar for submarine detection. The mounted patrols were disbanded on Feb. 18, 1944, and the active-duty Coast Guardsmen were transferred to other stations. Some of the horses were returned to the Army and others sold at public auction.

While the work was routine and seldom spectacular, there were many times when the beach patrol aided sailors and small craft in distress. Its most important contribution was the manning and development of the Coastal Information System as a guard force in policing the coast against a formidable enemy.

As the years have passed, most of the physical evidence of the World War II Coast Guard Mounted Patrols has vanished and most people living in North Carolina don’t know about a time when war came so close to our shores. The Coast Guard Mounted Patrols are reminders that military security duties on the home front are often as essential to victory as the front lines.

Credit and thanks are due to Mrs. Debbie Mollycheck, who authored the Mollycheck Collection, for her exhaustive research on the mounted patrols at Smith Island. She is the granddaughter of Franto “Dock” Mollycheck II, who was the Cape Fear Lighthouse keeper from 1937-1951. Special credit is also due to the research of Barbara Hubbard Wilson whose brother, Jack Hubbard, was a Guardsman at the Oak Island facility, and to Dr. Liz Fuller of the Southport Historical Society for her research and contribution.