The Sinking of the Sumner

BY Ashley Newman-Owens

The story should stop at the testimony of the first mate. But of course it doesnt. The boat was in the hands of a crew of eight. They were the West Indian seamen Leonida Edassarias Aylando Frank Aylando Quinonnes and Ramon Gonzales; the steward Charles Wallace; the second mate P. J. Antione of Louisiana; the first mate Charles Lacey of Mobile Alabama; and the skipper Robert E. Cochrane (Cockram Corkum) a 24-year-old from Bath Maine voyaging on his first command. Cochranes recent promotion had come at the end of five years during which he and Lacey served as first and second mates under former Captain Williams. H Had you been among the hundreds enjoying the beach that late summer Sunday afternoon chances are you would have seen her the three-masted schooner William H. Sumner making her way northward. Built in Camden Maine in 1891 she registered 489 net tons measured 165 feet in length with a 35-foot beam. The Puerto Rican-owned ship was chartered for the phosphate trade and was on this day Sunday September 7 1919 bound from San Juan for her home port in New York carrying 850 tons of phosphate as well as 56 mahogany logs and 30 tons of iron wood.

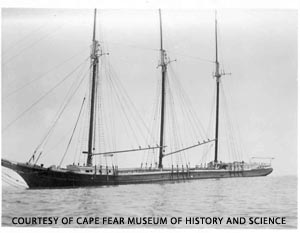

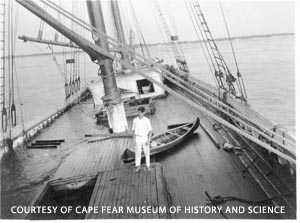

Had you been among the hundreds enjoying the beach that late summer Sunday afternoon chances are you would have seen her the three-masted schooner William H. Sumner making her way northward. Built in Camden Maine in 1891 she registered 489 net tons measured 165 feet in length with a 35-foot beam. The Puerto Rican-owned ship was chartered for the phosphate trade and was on this day Sunday September 7 1919 bound from San Juan for her home port in New York carrying 850 tons of phosphate as well as 56 mahogany logs and 30 tons of iron wood.

According to Lacey the ship had indeed gotten off course and sailed too close to shore and the skipper had planned to tack back out to sea at 8 p.m. But when the time came the winds had died and the currents had borne the vessel towards the shoals of Topsail Inlet. The ship then ran aground according to the first mate and by morning was thoroughly beached on the sand bar with eight feet of water in her hold.

According to Lacey the ship had indeed gotten off course and sailed too close to shore and the skipper had planned to tack back out to sea at 8 p.m. But when the time came the winds had died and the currents had borne the vessel towards the shoals of Topsail Inlet. The ship then ran aground according to the first mate and by morning was thoroughly beached on the sand bar with eight feet of water in her hold.

These were the facts as Lacey attested them when he arrived in Hampstead around noon on September 8 and telegraphed the agents of the William H. Sumner in New York. And these facts were the reason (according to Lacey) that Captain Robert E. Cochrane was now dead by his own hand having shot himself in an apparent “fit of despondency” at 6 a.m. Monday morning.

The story should stop there

an otherwise usual shipwreck with an unusually tragic ending. But over the days and weeks that followed the first mates report proved a mere preface to the saga that sprang up around the case of the Sumner.Lacey freely repeated his facts to the locals who noted him as calm and “unusually intelligent ” fluent in English Spanish and French. He returned to the ship where he assumed command and waited with the rest of the crew for the tug Blanche. The tug was expected to arrive that night and attempt to pull the vessel off at high tide at 5 a.m. the following morning. The Coast Guard cutter Seminole was dispatched to follow the tug to provide further assistance should it be needed; difficulties in floating the ship were anticipated since she had taken on so much water already.

But even as the sea set about burying the ship beyond recovery suspicions and possibilities were emerging that would linger for years in the minds of locals. The suicide story investigators quickly learned was hardly watertight.

Wilmingtons Morning Star which had broken the story on Tuesday September 9 with the decisive headline “Skipper Commits Suicide Because His Ship Went Ashore Off Topsail Inlet ” was singing an entirely different tune by Thursdays edition. “Murder on the High Seas Will Be Charged Against Crew of Foundered Ship ” it proclaimed; “Suicide is Discredited ” a subheading continued. In the interim the following events had unfolded:

At 8 a.m. on Tuesday the vessel split in two amidships before the tug Blanche could pass a line to her.

At 8 a.m. on Tuesday the vessel split in two amidships before the tug Blanche could pass a line to her.

Five hours later (at 1 p.m.) the skippers body in especially poor condition death having occurred 31 hours prior (according to Lacey that is) was removed by Will Pearsall the acting coroner for Pender County who assembled a jury of six men and commenced investigation.

On Tuesday evening after questioning the crew members four of whom did not speak English the jury recommended to H. P. Whitehurst of New Bern the United States District Attorney appointed to the case that all seven men be held pending further investigation. The jury was “unwilling to accept the theory of suicide as the cause of the skippers death” and advised further involvement of federal authorities.

On Tuesday night Mr. Whitehurst forecast possible “startling developments” to come the following day and when Wednesday arrived that proved true.

New evidence cast substantial doubt on the plausibility of the suicide explanation. Two separate wounds were found on the captains body: his right ear lobe had been shot away and a bullet pierced his head between the temples. There were no powder marks on his face. The ships log maintained by the mate contained no mention of the ships having been off its course Sunday afternoon nor even of the captains death. The last entry read solely “Ship beached and anchor lowered.” A number of the captains personal letters were found and all said Whitehurst were “of cheerful tone.”

A theory began to take shape in the minds of the investigators and gained popularity among an increasingly intrigued public: Rations on the ship were running low it was posited and the crew demanded that the captain put in for supplies. Perhaps he refused; perhaps the crew mutinied; perhaps they seized control of the ship. “It is suggested ” the Morning Star reported on September 11 “that the course might have been lost and the vessel hopelessly involved in the countless shoals off the Carolina Coast resulting finally in her going ashore. Assuming that this premise is correct it is believed that the crew with ship aground and discovery imminent killed the captain.”

As questioning wore on suspicious eyes settled on Charles Lacey. Though all crew members had initially corroborated the suicide story three were said to have broken down after three days of questioning. Charles Wallace the steward identified himself as the first of the crew to have discovered the dead captain. Wallace maintained that just minutes before 6 a.m. Monday morning the captain had come forward to survey the ships predicament.

“He said to me We have got to get out of this some way and returned to his quarters in the afterdeck. All of the crew except the mate and second mate were forward. The mate was lying on top of the deck house at the port quarters when the captain entered his quarters … As I was going aft I met the mate Lacey going forward. He was walking rather briskly. I entered … the captains quarters and I saw the captain lying on the floor of the cabin bleeding.”

Wallace also reported that Lacey had a bad reputation on the ship and off. Rumors were rife: In Puerto Rico a few days before setting sail the mate had had “a shooting scratch with a native.” Lacey had twice tried to kill the captain already once by throwing a lantern once with a knife. He had threatened and abused the captain for his handling of the ship after the Sumner had grounded. He had carried the captains revolver in his belt during the night and boasted of his own marksmanship.

Two other crew members were said to corroborate the thrust of Wallaces story that “the mate was lying on the window from which it looked like the shot was fired” and spoke of Laceys “naturally vicious and trouble-making disposition.” All of their testimony however came through an interpreter Nicolas Morel who was the nephew of the Chilean president and of the former Chilean ambassador in Washington.

Meanwhile the other three crew members insisted Lacey and Wallace were friends.

The crew was arraigned on September 22. Lacey argued in his own defense that he had been “directed to remain on deck all night and had taken the small boat cover and laid down on it to rest a little before dawn.” Probable cause was established to try him in federal court on November 19. Though Whitehurst advised that the rest of the crew be dismissed all men were held in jail in default of bonds of $1 000 each.

At the November 19 trial with conflicting stories persisting a jury deliberated for 26 hours and still failed to agree on a verdict splitting seven to five in favor of guilt on the charge of first-degree murder. Lacey refused to plead guilty to a lesser charge opting instead to await a new trial in the next session of federal courts the following May. His decision kept all the crew jailed until then.

In the spring the same arguments were again presented. Prosecutors noted the absence of powder marks on the captain and the location of the bullet found in the cabin wall in direct line they argued with the broken window through which the shot was assumed to have been fired.

Charles U. Harriss of Raleigh argued on Laceys behalf invoking a captains frequent resolve to go down with his ship.

For reasons not clear the proceedings were decidedly abbreviated this time. Perhaps the frenzied climate surrounding the initial trial had grown calm over the months intervening; perhaps it was a matter of mere chance. Whatever the responsible factors the jury deliberated a brief ten minutes then rendered a verdict of not guilty.

After voicing his relief “Thank God! Thank God!” Lacey declared himself homebound swearing hed “catch the first thing that smoked for Alabama.”

The true details of what transpired aboard the William H. Sumner nearly a century ago are buried fathoms deep no more salvageable than the 850 tons of phosphate lost to the inexorable action of decades and the elements. The bulk of what didnt sink was blown up by the Coast Guard within a week of the wreck having been deemed a menace to navigation.

But shrouded in mystery though it is theres a certain specificity to the Sumner a concreteness that enchants many North Carolinians to this day. And in at least one very real way the Sumner does remain accessible: a piece of the deck measuring about 28 by 11 feet and mostly buried by the beach after it washed away from the main wreck site reveals itself periodically in Surf City thanks to strong northeast winds that shift the sand. “This year it was more exposed than Id ever seen it says Nathan Henry the North Carolina Archaeology Branch conservator at Fort Fisher. The apparition is fleeting generally receding again within a day but those eager to catch a glimpse can count on future opportunities.

“Its more than just a cool story ” says Henry. “Its something we can put a name on. So often with wreck fragments they could have come from any ship.” But the Sumner is the only wreck structure on Topsail that ever becomes visible and according to Henry its unmistakable: “Its easy to pinpoint which wreck that is just by the structure of the vessel.”

Note: All unattributed quotes are excerpted from editions of the Wilmington Morning Star between September 9 and September 23 1919.