The Art of Henry Jay MacMillan

Wilmington artist Henry MacMillan was embedded within World War II’s most treacherous battlefields

BY Robert Rehder

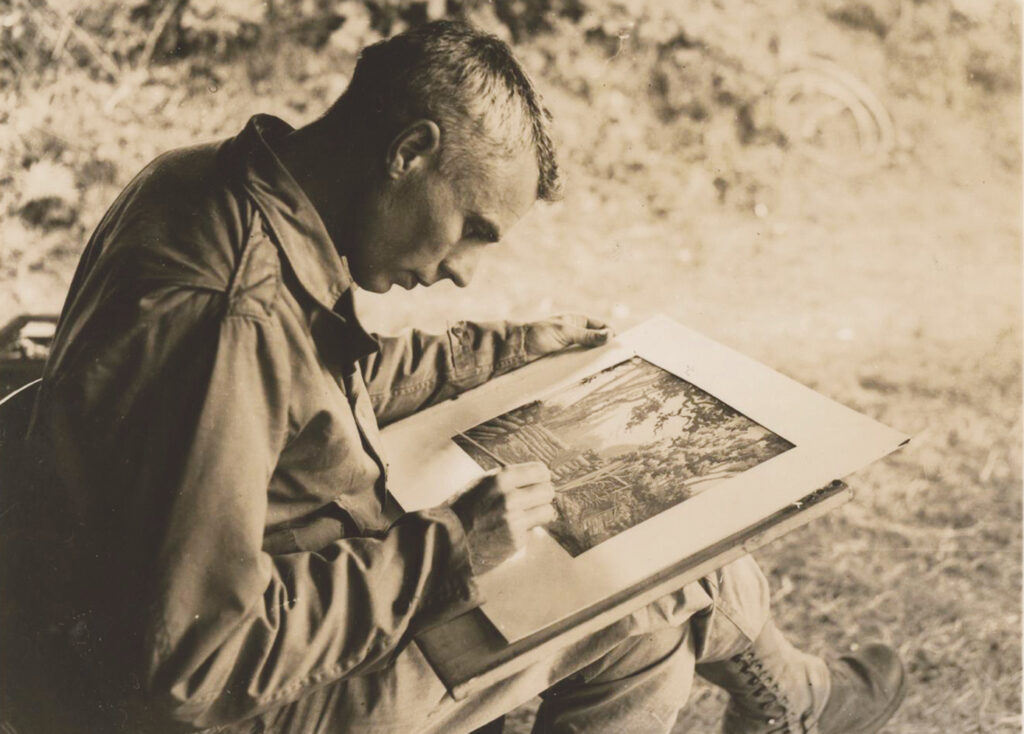

During World War II, more than 100 U.S. servicemen served as combat artists. In addition to their combat duties, they depicted war scenes through sketches, watercolors and oil paintings. Their stories are seldom told and their artwork, consisting of more than 12,000 pieces, has been largely forgotten.

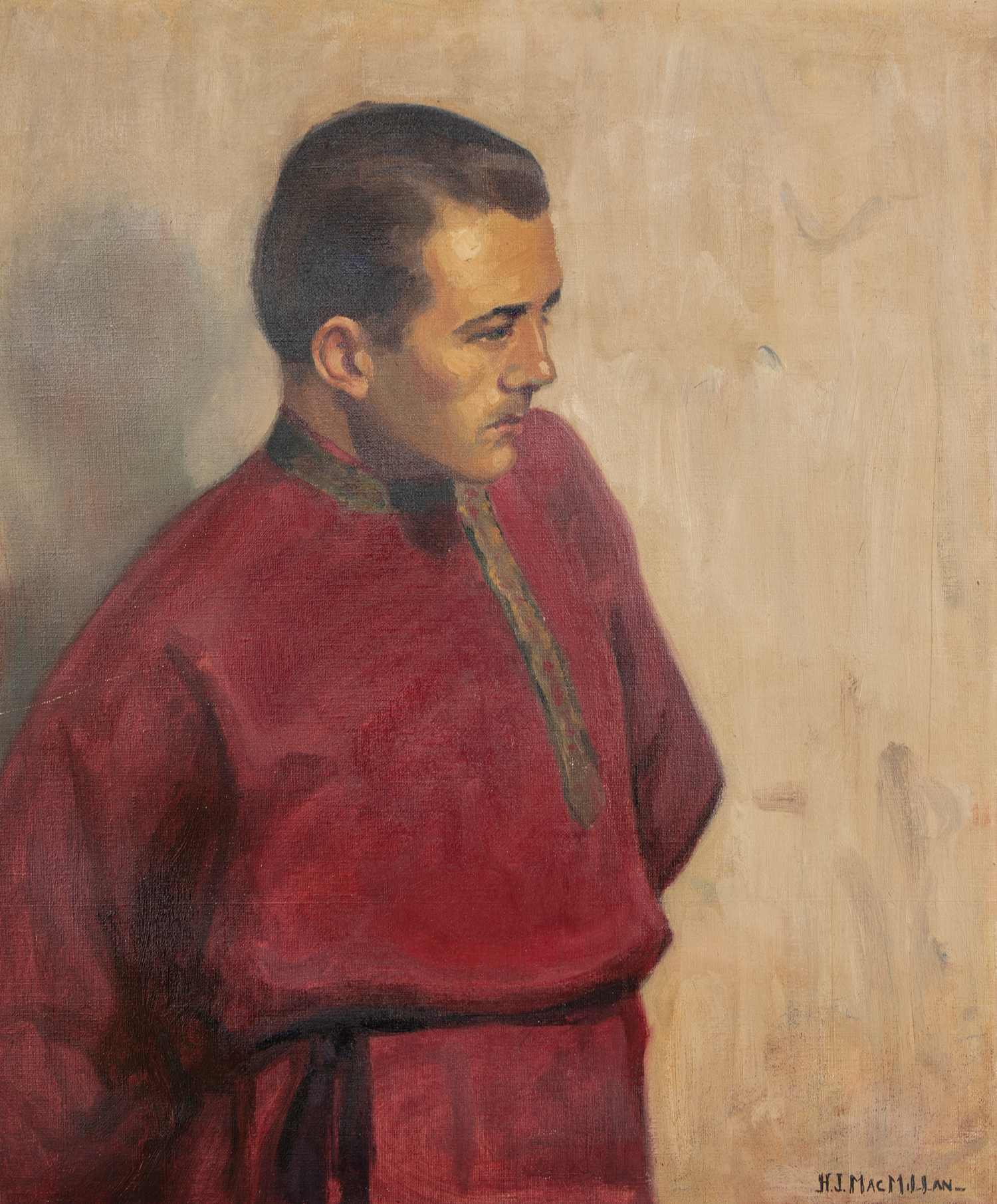

One of those artists was Henry Jay MacMillan, artist, painter, decorator, designer and Wilmington son. You may have seen his tasteful, striking portraits of Wilmington family members, or his scenic New Hanover County watercolors, but you may not be familiar with the stunning wartime illustrations from MacMillan’s Army service in Europe.

In his celebrated lifetime, MacMillan (1908-1991) enjoyed a distinguished presence in Wilmington’s art community. Born and raised here, he graduated from New Hanover High School, apprenticed under renowned artist Elisabeth Augusta Chant, and painted from his studio at his home on Fourth Street in Wilmington’s Historic District. He studied art and design at the Parsons School of Design in New York and graduated from its Paris campus in 1929.

Grounded by family and tradition, he was blessed with a strong foundation and sense of vision from his parents, Jane Meares Williams and Henry Jay MacMillan Sr. He had a deep, clear voice, an intense gaze, and an often-intimidating, straightforward presence. Sophisticated, enigmatic, perhaps even courtly, he moved and laughed with ease, his most colorful moments occurring impromptu.

Impeccably dressed and well-mannered, he had significant friendships, entertained often, and as a young artist enjoyed Wilmington’s prewar social scene. He was involved with many events that shaped Wilmington’s art, his constant motivation being unwavering love and devotion to his family and nurturing his city’s art community.

Wilmington was a quiet, peaceful place, but by the spring of 1942, as Europe was increasingly engulfed in war, German submarines began harassing American shipping just off the North Carolina coast, bringing the winds of war closer to home. It was a tumultuous year for MacMillan, who at age 35 was making a comfortable living as a portrait and landscape artist. That changed abruptly when he was inducted into the U.S. Army.

After infantry training and temporary duty at Fort Bragg, he was transferred to the 62nd Engineer Topographic Company, a mapping outfit operating out of Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Then in 1944, the 62nd was assigned to the First and Ninth U.S. Armies in France and Germany. MacMillan and the 62nd arrived in France just days after the D-Day invasion, June 6, 1944.

A mixture of bravado and terror seemed to animate war artists, and MacMillan was no exception. Never reluctant to put himself in danger, he sought to convey the reality of war through firsthand experience.He explored the visual and sensory dimensions of warfare that are often absent in battle accounts. He was a soldier first but also specifically commissioned to be in the most dangerous areas to observe military activity. He recorded war in ways that cameras could not, collecting experiences from the people who endured and the places that survived.

He found his subjects in perilous areas and created the most painful sequences in his own style to convey the reality of war. He could illustrate the very soul of a battle and describe mournful, battle-weary scenes while at the same time omitting the harrowing side of humanity. His focus was on ordinary soldiers set against the ash-gray ruins of the towns where they fought. Never metaphoric, his art drew the war as realistically as possible — a style evident in his depictions of the devastating hedgerow action in Normandy, France.

The hedgerows of Normandy, which saw furious fighting after D-Day, were MacMillan’s first assignment. His initial works were watercolor landscapes of the hedgerows and nearby towns, several of which show the ruins of once-lovely French villages destroyed by war.

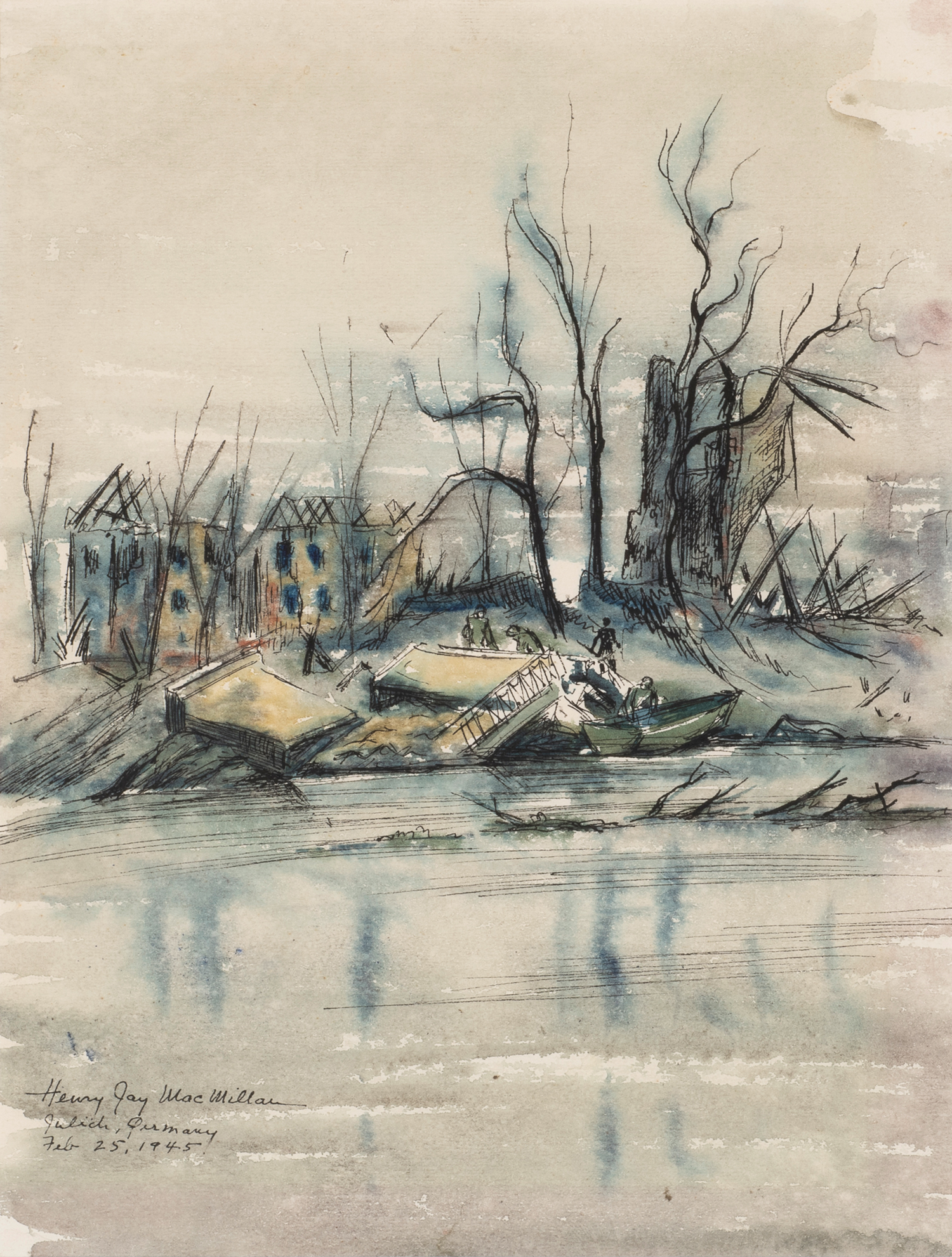

Realism was the constant in MacMillan’s art, which poignantly illustrated the antipathy of combat. His haunting watercolor The Ruins of Palace de Justice at Saint-Lo shows the ruined city with a bomb crater in the foreground surrounded by rubble. His powerful watercolor Roer River Ruins, at Julich, Germany depicts bare trees shredded by artillery with ruined buildings in the background.

No abstract expressionist, MacMillan created a historic, aesthetic record of the war. His compelling images in North Africa, Sicily, Belgium, Holland, Germany, and foremost in Normandy, instill on canvas the raw essence of war. Some 60 works are permanently housed at Wilmington’s Cape Fear Museum of History and Science and comprise a major body of watercolors and sketches documenting destruction, battlefield landscapes, and everyday military life.

A proud veteran and recipient of the Bronze Star, he was honorably discharged in 1945 and returned to America initially to teach at the Parsons School and work in New York before returning to Wilmington. He entered the city’s active, post-war cultural life, as always building an environment for the appreciation of art, becoming a well-known portrait artist.

Given his significant experiences in Europe, he had much to talk about in the years after the war, and the MacMillan home once again became a busy place of family get-togethers, birthdays, celebrations, art and camaraderie. MacMillan immensely enjoyed his second home at Wrightsville Beach’s Asheville Street, the scene of some of his finest work and many celebrations attended by family, friends and supporters of the arts. Increasingly, he retreated to his home in Wilmington where he painted from his second-story studio and entertained his closest friends.

In 1973, he donated most of his war artworks to the Cape Fear Museum of History and Science, which held exhibits of his work in 1994 and 2021. Along with his wartime watercolors and pen-and-ink sketches, the museum houses his Army gear, Bronze Star, and soldier’s metal identity tags. MacMillan’s artwork has also been featured on the World War II website maintained by UNCW’s Randall Library.

A talented writer and historian, in 1990 he wrote Violet & Gold, the story of Wilmington artist Elisabeth Chant, his teacher, friend, and mentor, and the artistic activity on Cottage Lane in Wilmington. Generous with his time, he was a founding member of the Wilmington Museum of Art in 1938, and the Lower Cape Fear Historical Society

in 1956.

Over the course of his distinguished career as an artist, illustrator, historian and decorated combat artist, he earned a prominent presence in Wilmington. His acclaimed work stands the test of time and speaks to a unique era and a dramatic and decisive time in his life.

Henry Jay MacMillan, graceful, brave, and benevolent Wilmingtonian, died at his home in 1991 at the age of 83.