Tartan Spirit

BY Dorothy Rankin

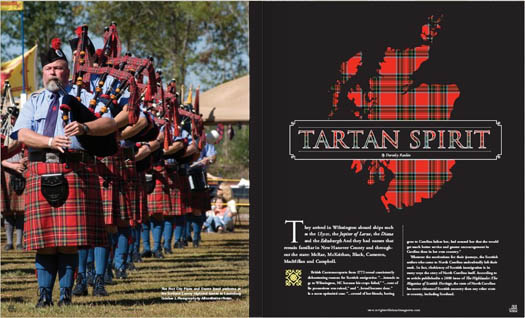

They arrived in Wilmington aboard ships such as the Ulysses the Jupiter of Larne the Diana and the Edinburgh. And they had names that remain familiar in New Hanover County and throughout the state: McRae McKeithan Black Cameron MacMillan and Campbell. British Customs reports from 1772 reveal consistently disheartening reasons for Scottish emigration: “intends to go to Wilmington NC because his crops failed ” “…rent of his possessions was raised ” and “…bread became dear.” Whatever the motivations for their journeys the Scottish settlers who came to North Carolina undoubtedly left their mark. In fact the history of Scottish immigration is in many ways the story of North Carolina itself. According to an article published in a 2000 issue of The Highlander: The Magazine of Scottish Heritage the state of North Carolina has more citizens of Scottish ancestry than any other state or country including Scotland. The history of North Carolina therefore is closely tied with the political and social history of England Scotland and Ireland. A conversation with Ron McCord current president of the Scottish Society of Wilmington captures much of the intertwined nature of these countries as well as the convoluted history of the Scottish people. “Scots-Irish” is a term that appears early in McCords remarks but while many families use the term to refer to their heritage not all of them know exactly what that description entails. “Theyre called Scots-Irish ” McCord explains “but they arent really Irish except maybe they were Celtic folks from years ago.” McCord says that many of these families also known as Ulster Scots were part of an English plan to control the Irish Catholics. In the 1600s the English controlled all of Ireland but they were having trouble with the native population so they established what was known as the Irish Plantations by replacing five Irish earls with Scotsmen more sympathetic to the government. They then relocated a number of Lowland Scots into Irish territories. Once there the Protestant Scots often did battle with the Irish Catholics. By early in the 18th century they were beginning to prosper. The English reacted by raising their rents and enacting laws that restricted trade of their successful linen manufacturing. Later confiscation of property and increased taxes further strained relations between Scottish people and the English government. The early to mid 1700s saw a migration of those who had gone from southern Scotland to the Irish Plantations and then to America McCord says. Some had intermarried with the local population cementing their ties with Ireland so when they came to this country “they were pretty ticked off with the English.” As a result McCord continues “most of the Ulster Scots were patriots. About a third of Washingtons army was Ulster Scots.” Loyalists McCord explains “were primarily Highland Scots ” whose immigration was often spurred by economic factors. “They tended to sign loyalty oaths to the English because they [the English] paid for them to come over here so when the revolutionary war broke out they were the supporters of King George.” Most of the battles in the Carolinas McCord says were primarily between Highlander Loyalists and Ulster Scots Patriots. Often only a few of the English were even involved. The battle of Kings Mountain involved one Englishman who was McCord explains “commander of the Loyalist army. Moores Creek was the same way.” Although Wilmingtons port played a role in the Scottish migration records indicate that a great many of the earliest arrivals didnt linger along the lower Cape Fear. North Carolina History Project explains it this way: “Countless Highland Scots migrated to North Carolina during the colonial period. Arriving in Wilmington most who came had obtained a land grant from the government to settle in the Upper Cape Fear region because they knew many parts of the Lower Cape Fear had been settled. In 1754 enterprising merchants from Wilmington had settled Cross Creek an interior town on the Cape Fear River so many Highlanders dwelled near the small creeks flowing into the river. The Lowland Scots who migrated from Scotland to North Carolina in the eighteenth century primarily settled in the Lower Cape Fear region around Wilmington.” Clearly Wilmington feels a connection to its Scottish roots a connection that is nurtured by the Scottish Society of Wilmington. Formed in 1993 the society was established to promote and preserve the “Scottish heritage and culture and to provide kinship and fellowship among all those of Scottish ancestry.” Although many of the societys members can trace their lineage back to their Scottish forbearers proof of Scottish ancestry is not required. McCord is quick to emphasize that membership is open not only to Scots but anyone interested in Scottish heritage. Nancy and Press Millen longtime members of the Society reinforce that idea. North Carolina natives who retired to Wilmington the Millens now divide their time between Chapel Hill and Wrightsville Beach. For them the Scottish Society is all about making connections. “Its not a closed organization; its very welcoming ” Nancy says. “Weve met a lot of nice people through it that we might not have known otherwise.” One of the primary functions of the Society is to celebrate those things that are uniquely Scottish. To that end it schedules a series of events throughout the year. According to Nancy Millen “The biggest thing that the Scottish Society does and its open to everybody is the Bobbie Burns dinner. We attract people from all over for that.” The supper is held every year close to the anniversary of the birth (January 25) of Robert Burns who is generally acknowledged as the national poet of Scotland. As Nancy says the dinner “has its rituals.” Those include a multitude of toasts and traditional Scottish delicacies including haggis which is ushered into the hall accompanied by a bagpiper. Haggis is a kind of savory pudding usually made of sheeps organs mixed with oatmeal onion suet and spices and encased in the sheeps intestine like sausage. The FDA wont allow importation of authentic Scottish haggis so the Americanized version is made from sirloin flavored with traditional spices and stuffed into casing. McCord who has eaten both confides that the domestic version is “a little tastier.” Another important event on the Societys calendar is the Kirkin O The Tartan which occurs in October at the First Presbyterian Church in Wilmington. During the event which celebrates the rich heritage of the Scottish Reformation a piper leads a procession of clan representatives each carrying their clans banner or tartan which is then displayed on a stand at the front of the church. While many Scottish families are proud of their tartans marriage and passing generations can complicate clan connections. When the time comes to carry their clan colors into church “some people ” Press Millen says “could march with 10 banners easy.” Nancy attributes her initial interest in the Society to the Kirkin O The Tartan. “We think its a wonderful thing.” Her husband agrees. “The Scottish Society is certainly not made of all Presbyterians but it doesnt matter. A lot of them come.” Diane McCord Rons wife also appreciates the ritual. The first one they attended was done “like they did it in the 1600s. So the women were all on one side of the church; the men were on the other side of the church. And they locked the door when you came in.” The minister she says explained “Thats not to keep you in; thats to keep the devil out.” The Scottish Society also has a presence at the commemoration of the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. Although the group is not directly involved with the reenactment of the Pender county battle pitted former Scottish countrymen against each other the Society does attend the event distributes information and lays a memorial wreath. The Ceilidh (pronounced “Kay-lee”) is usually a social gathering for the Society although this past spring it was used as a fundraiser to help provide the money to send a young piper to a workshop in Valle Crucis. Originally a Ceilidh was an informal gathering where guests would participate in music dancing or singing. The Societys Ceilidh usually provides professional entertainment although their own members many accomplished musicians and singers also perform. A Ceilidh is also frequently held at highland games. These competitions are an important part of the celebration of Scottish culture. Although the gatherings are held around the world North Carolina is home to a number of well established games. Perhaps the best known of these is connected to Wilmington through Hugh McRae a Wilmington native and great great grandson of Scottish immigrants. McRae acquired acreage in Avery County that his grandson Hugh Morton would eventually inherit and develop into Grandfather Mountain. 2011 will mark the 56th Highland Games at Grandfather Mountain. According to Ron McCord the Grandfather games are the largest in the United States in terms of the number of clans that participate. “Theyll have 140-150 clans attend.” Although Grandfather Mountain may host 25 000 spectators other games are even larger. The highland games in San Francisco for instance boasts 40-45 000 people over the weekend. North Carolina has several smaller but still impressive games including Loch Norman (near Charlotte) and Laurinburg. In addition to athletic competitions (caber tossing track and field events and hammer throw) highland games feature competitions for pipe and drum Highland dancing Scottish fiddle and Celtic harp. They also involve tents or booths for participating clans. Ron McCord is usually responsible for the Clan McCord tent and he offers to help visitors who are interested in trying to find their Scottish roots. He has lots of takers. As he and Diane both agree “Most everybody wants to be Scottish.”

In a more optimistic case: “…several of her friends having gone to Carolina before her had assured her that she would get much better service and greater encouragement in Carolina than in her own country.”