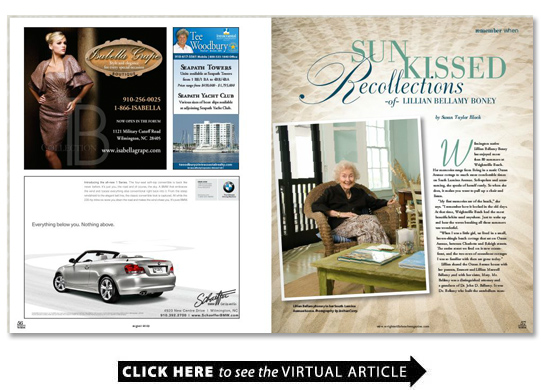

Sun-Kissed Recollections of Lillian Bellamy Boney

BY Susan Taylor Block

Wilmington native Lillian Bellamy Boney has enjoyed more than 80 summers at Wrightsville Beach. Her memories range from living in a rustic Ocean Avenue cottage to much more comfortable times on South Lumina Avenue. Soft-spoken and unassuming she speaks of herself rarely. So when she does it makes you want to pull up a chair and listen.

“My first memories are of the beach ” she says. “I remember how it looked in the old days. At that time Wrightsville Beach had the most beautiful white sand anywhere. Just to wake up and hear the waves breaking all those summers was wonderful.

“My first memories are of the beach ” she says. “I remember how it looked in the old days. At that time Wrightsville Beach had the most beautiful white sand anywhere. Just to wake up and hear the waves breaking all those summers was wonderful.

“When I was a little girl we lived in a small brown-shingle beach cottage that sat on Ocean Avenue between Charlotte and Raleigh streets. The entire street we lived on is now oceanfront and the two rows of oceanfront cottages I was so familiar with then are gone today.”

Lillian shared the Ocean Avenue house with her parents Emmett and Lillian Maxwell Bellamy and with her sister Mary. Mr. Bellamy was a distinguished attorney and a grandson of Dr. John D. Bellamy. It was Dr. Bellamy who built the antebellum mansion that sits majestically at the intersection of Market Street and Fifth Avenue. As a young woman Lillian along with her cousin Emma Bellamy Williamson Hendren inherited ownership of the Bellamy Mansion. It was an enviable real estate position that the two women held for 40 years and their preservation efforts may well have saved the elegant landmark now a renowned museum of history and design arts.

Other local residences with which Lillian had intimate ties were her parents’ home at 1419 Rankin Street and the imposing house of her grandfather Congressman John D. Bellamy Jr. at 603 Market Street. But at Wrightsville Beach things were more democratic. In those days cottages were just that — cottages. “The houses were very simple generally then ” Lillian says. “Now if you lose a house at the beach you lose something special but in those days they weren’t very special.

“Living at Wrightsville was just delightful. We spent the day on the beach and we were freckled and fried all the time. We had no air conditioners then so we slept under mosquito netting at night just in case the “no-see-ums” showed up. No cars were allowed on the beach because there were no roads. It was a little inconvenient but it was nice and peaceful. We usually moved to Wrightsville by driving over to Harbor Island and parking our car there in a lot run by the folks who owned Shore Acres. Then porters came along with little wooden wagons to tote our belongings to the beach car. We would get off the beach car just as close to our house as possible so we didn’t have to carry our things too far.”

Lillian and Mary swam in the ocean in front of their cottage but were taught to be extra cautious. There were no lifeguards in that area at the time and a number of drownings occurred — especially when folks who were used to swimming in lakes and ponds encountered rip currents. The closest lifeguards were at the Oceanic and the Seashore Hotels and at Lumina. Lillian still remembers the name of the Lumina lifeguard who was also a wrestler: Fritz Hanson.

“Our family went to church at Little Chapel on the Boardwalk. It was not where it is now. It was on the south end of the beach between the Blockade Runner and Station One. It was a little wooden building and it was jointly maintained by the First Presbyterians and St. James Church. And hot — oh it was hot! We all had fans and everybody used them.

“Our kitchen might have been the hottest place of all. Beach living was primitive life during my early childhood. We had a wood cook stove and there was a live fire in it during those sweltering days of summer. I don’t know why our cook didn’t just cry. But she didn’t and she served us good things to eat.

“We had an icebox when I was a little girl and the ice man came everyday and brought ice. It was just a big box with insulation and that was how things were kept cold then. By about 1930 we had our first real refrigerator.”

In the 1930s the beach was a quirkier place. One day shortly after returning home from the hospital the Bellamy family’s faithful cook was accused of being a bootlegger and arrested at their cottage. Mr. Bellamy posted bail that same day and the cook returned to work. Juxtaposed was the scene at the neighbors Mr. and Mrs. George Kidder. The senior Kidders along with their children Roddy Kidder and Anne Kidder Beatty dressed formally for dinner every night. The males wore dinner jackets and the females donned long evening dresses.

Like most every young summer resident Lillian rode the beach car to Children’s Night at Lumina once a week. “Out of the darkness the lights at Lumina were dazzling ” Lillian recalls. “On Children’s Night we would watch the movies on the screen over the ocean. They were silent movies so we were fairly scornful of them. We didn’t think they were so wonderful because we were just old enough to notice the difference between talkies and the silent movies. But it was a large big screen out there in the water.

“Then we would go on Saturday nights and watch the pretty older girls like Fonnie Moore (Dunn) Lilly Robertson (Klein) Anne Kidder (Beatty) Alice James (Grainger) Louise Worth (Boylan) Lossie Taylor (Noell) Peggy Moore (Perdew) and Margaret White (Grainger) dance. But Catherine Meier was the ultimate dancer at Lumina in those years. She would always be down in a corner dancing with a man named Bill Beery who worked at the Atlantic Coast Line. They were so good together.”

As testimony to the slow pace and relaxed sanitation rules Lillian’s pet duck named Pete “went everywhere” with her on the beach. Pete who had been given to Lillian as an Easter present enjoyed fishing for small catches. When Lillian would play the piano he would “quack” to the music. Pete even waddled along when Lillian and her friends went to Newell’s (the iconic variety store located where Wings sits today). Mrs. Newell didn’t even protest when Pete went inside with Lillian and waited while she ordered ice cream. However she did show all the children the door when she discovered them reading periodicals for free. “We would all slip over and read funny books and she would always find us ” Lillian remembers.

Pete the Duck’s happy days at Wrightsville Beach came to an early end after he became a little too attached to his young owner. “Pete was protective of me and could get very belligerent when my friends came to see me ” Lillian says. “He would chase them around the yard. Eventually he had to go to live with some other ducks at my grandfather’s little farm over in Brunswick County called Grovely. He disappeared about the same time we had a family Christmastime dinner one year and I have never eaten duck since.”

Lillian and her childhood friends had plenty of distractions when wealthy Jessie Kenan Wise began building a beach house in their neighborhood. “There in the depths of the Depression she built a perfectly enormous cottage. It sat just half a block from where we lived. Everybody was fascinated with it. Later it was bought by Mrs. Ina McNair Avinger from Laurinburg. The house is still there at 9 East Raleigh Street.”

As time passed the land on Ocean Avenue continued to erode and high tide crept ever nearer the Bellamys’ cottage. Then in 1934 the famous beach fire that began in the Kitty Cottage burned their home. Emmett Bellamy rebuilt on the same lot within a few months. Their new cottage featured a flat roof a rare thing at the beach in those days.

“Our new cottage was strange looking because of that roof ” says Lillian “but I don’t ever remember it leaking. There was a boardwalk in front of our house and one or two rows of cottages between us and the ocean. The erosion continued and as the sand receded the boardwalk seemed to sit up higher and higher. It was probably eight feet off the ground. I remember my mother and father had a party in the middle of the day and served The Cape Fear Club Punch. When the guests got ready to leave two or three of them accidentally leapt off the boardwalk. They didn’t get hurt they just flew through the air and landed on their feet in the soft sand. I would say they were definitely feeling pretty relaxed.”

Lillian and her young friends entertained themselves by visiting the boardwalk café Pop Gray’s which sat near the corner of South Lumina Avenue and Causeway Drive. Pop Gray’s was an interesting “hangout ” where artist Claude Howell sketched and where Lillian’s uncle Leeds Barroll fresh back from residency in Europe called to servers saying “Garcon Garcon.” Prohibition tamed the drink menu so that both adults and young people were served the same beverages.

At Pop Gray’s Lillian and her friends put into practice dance steps they learned at Lumina. “There was a jukebox there ” says Lillian “and we teenagers would dance the Big Apple and Little Apple. Bryan Broadfoot and Frances Thornton were two of the best dancers there. There also was a jukebox at the Ocean Terrace Hotel and that is where my parents gave me a dance party when I turned 12.”

By the time Lillian was 16 World War II had changed things on the beach. The Bellamy family kept blackout shades over the windows stayed in the cottage after six o’clock every evening and were only allowed a ration of five gallons of gasoline a week. Oil slicks from merchant marine ships sunk by enemy vessels served as reminders of the seriousness of the situation. Lillian traveled from the beach to town most summer days to work as a plane tracker in a secret office at the downtown post office and as a volunteer with the American Red Cross. “The Red Cross even taught us how to deliver babies and change tires ” Lillian says. “I’m glad I never had to do either.

“There were some tense moments though. One night an alarm went off on the beach. The man who lived next door to us suddenly turned on every light in his house — a forbidden thing to do at the time. Just in case enemies were lurking offshore looking for a lighted target my father climbed up on the flat roof of our house and yelled for him to turn his lights off. Almost immediately patrolmen came to our house with their guns drawn.”

While the war continued the proverbial sands of time did too. Eventually the high tide watermark was under the Bellamy House. “My gracious ” Lillian says “George Clark’s father our neighbor began surf fishing from the upstairs porch of his parents’ cottage. That was just the thing he would do in that crisis because he was the ultimate fisherman. For years he had been going out there surfcasting and he would reel in the fish when nobody else could catch any. He just had the magic touch.”

Emmett Bellamy sold the beach house and they moved into his father’s house on the southern end of the beach around 1947. Mayor Solomon Fishblate built the house located at 315 South Lumina Avenue before 1900. Mr. Fishblate built a waterfront house in Wilmington too at 318 South Front Street. Both houses still stand.

In 1954 after a courtship of five years Lillian married architect Leslie N. Boney Jr. The couple was married at St. James Church on May 8 and the reception was held at the Bellamy Mansion. It was a rare treat for guests because the house was unoccupied and not open for tours at the time. It had not been open since 1946 when Lillian’s Aunt Ellen Bellamy died. Mr. and Mrs. Boney then sailed to Europe for a honeymoon that lasted six weeks. After they returned home they took up residence at Wrightsville Beach.

“Leslie and I stayed at the beach the fall of 1954. It was the most beautiful fall you can imagine. Then Hurricane Hazel came along October 15 ” Lillian says. Hazel caused significant structural damage to the John D. Bellamy cottage but the Boneys rebuilt the structure. “I still spend summers at the beach — in what’s left of the old house. About 1999 we had to raze a portion of the original house that survived Hurricane Hazel but we rebuilt using the same windows doors and architectural footprint of the old structure. However we added an extra story to the house. That was all supervised by my husband.”

Leslie N. Boney Jr. died in 2003 and was eulogized as one of North Carolina’s most celebrated architects and good citizens. Lillian continues to keep a keen interest in various charitable causes including historic preservation and the provision of nursing school scholarships for Native Americans. In 2002 a year before Mr. Boney’s death Leslie and Lillian Boney shared the Ruth Coltrane Cannon Award North Carolina’s most prestigious preservation award for their work in the preservation of the Bellamy Mansion the Burgwin-Wright House and in Raleigh Haywood Hall.

Today Lillian shares the beach house with her children — Emmett Boney Haywood Mary Boney Denison Clark and Leslie N. Boney III. Lillian’s grandchildren now make up the fifth generation of Bellamy descendants who have grown to cherish time spent at 315 South Lumina Avenue. “I tell them to seize the moment and really appreciate the house and the land ” she says with a face full of wisdom and a heart full of memories “because a lot of things can change on a beach.”