Still in the Fight

BY Simon Gonzalez

Semper fi until I die.

It’s not just a slogan on a T-shirt. It’s what Marines live and breathe every day.

Semper fi.

Always faithful ? to the uniform the Corps their country their band of brothers.

To the end.

The men and women of the U.S. Marine Corps are a special breed noted for their fighting spirit for their determination for their pride for their toughness. They exemplify the recruiting pitch first used over 235 years ago when Capt. William Jones advertised for “a few good men.” They are called and driven to be the best.

“It’s part of the identity as a Marine to be a leader to take care of other Marines. That’s what we do ” says Lt. Col. John Kelley.

They join the Corps to stay in the Corps. Nobody becomes a Marine to be an ex-Marine.

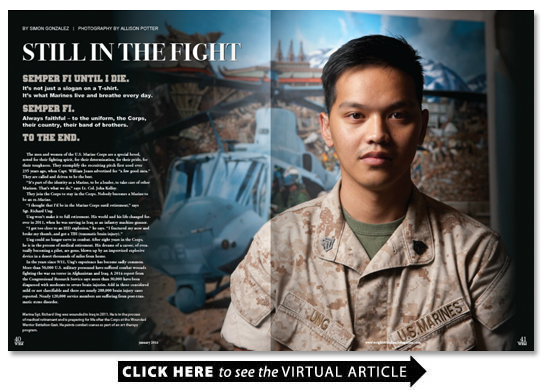

“I thought that I’d be in the Marine Corps until retirement ” says Sgt. Richard Ung.

Ung won’t make it to full retirement. His world and his life changed forever in 2011 when he was serving in Iraq as an infantry machine gunner.

“I got too close to an IED explosion ” he says. “I fractured my nose and broke my thumb and got a TBI (traumatic brain injury).”

Ung could no longer serve in combat. After eight years in the Corps he is in the process of medical retirement. His dreams of a career of eventually becoming a pilot are gone blown up by an improvised explosive device in a desert thousands of miles from home.

In the years since 9/11 Ung’s experience has become sadly common. More than 50 000 U.S. military personnel have suffered combat wounds fighting the war on terror in Afghanistan and Iraq. A 2014 report from the Congressional Research Service says more than 30 000 have been diagnosed with moderate to severe brain injuries. Add in those considered mild or not classifiable and there are nearly 288 000 brain injury cases reported. Nearly 120 000 service members are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Because of the nature of their mission about eight in ten Marines deployed overseas served in combat units. They suffered the brunt of the war wounds.

It is those wounds — physical and mental — that are forcing fighting men like Ung out prematurely. It’s not the way they imagined it would end when they enlisted.

If they leave they want it to be their choice. Instead it’s the choice of a medical board that tells them they can no longer serve.

“A lot of them planned to do 20 years 30 years in the Marine Corps ” Craig Stephens says. “Now they find themselves getting separated. It’s not what they planned to do.”

Stephens is the command advisor for Wounded Warrior Battalion-East. The unit is part of the Wounded Warrior Regiment which exists to provide assistance to wounded ill and injured Marines and sailors attached to Marine units to help them return to duty or to transition to civilian life.

The Wounded Warrior Regiment consists of Wounded Warrior Battalion-East headquartered at Camp Lejeune North Carolina and Wounded Warrior Battalion-West at Camp Pendleton in California along with detachments located throughout the country.

“Our mission is to get them to the medical board or back to the fleet. It doesn’t matter to us how you were injured we’re going to support you and your family ” says Stephens who served with the Marines for 30 years — the first 12 as an enlisted man — before retiring as a lieutenant colonel in October 2007. He joined the Wounded Warrior Battalion-East as civilian command advisor in August 2009.

The battalion includes a return to duty platoon that provides care and rehabilitation so Marines can go back to their combat units but for the majority of the men and women here their next duty station will be in the civilian world. About 95 percent of the 280-300 Marines at WWBn-E are on their way to medical retirement.

For Marines who long to be back with their units out on the front lines with their buddies it can be a difficult transition.

“Marines need to know they are still in the fight that they are not forgotten ” Stephens says.

Outside the headquarters of the Wounded Warrior Battalion complex is a bronze statue by John Phelps modeled on an iconic photograph by Lucian Reed taken during combat operations in Iraq in 2004. It depicts Marine 1st Sgt. Brad Kasal being carried out of Fallujah’s infamous “Hell House” by Lance Corporals Chris Marquez and Dan Shaffer.

Kasal received the Navy Cross for bravery for his actions that day. He was hit by multiple rounds and grenade fragments and lost approximately 60 percent of his blood. But he kept fighting and is credited with saving the lives of several Marines.

In the photo and sculpture his arms are draped around the corporals. His right hand continues to hold his weapon. His finger is on the trigger guard. Losing blood and critically wounded he was still in the fight.

The sculpture was donated by Hope For The Warriors a nonprofit intimately involved and engaged in the Wounded Warrior Battalion (see story on page 52). It is a fitting sentinel for the complex. “Etiam in Pugna ” or Still in the Fight is the motto of the Wounded Warrior Regiment.

“They are still fighters ” Stephens says. “They’re not pushed off to the side. They still have worth.”

The genesis of the Wounded Warrior Regiment was a combat injury suffered by Lt. Col. Tim Maxwell who sustained a penetrating head wound during his sixth combat tour in Iraq in 2004. While in recovery he noticed that injured Marines were often isolated and lacking a support system alone while their units were deployed.

He had the idea of gathering wounded warriors from around Camp Lejeune and putting them in a barracks. Marines who once fought side by side could now recover side by side.

What began as a barracks made up of 12 Marines in the fall of 2005 grew and expanded. In 2007 the Wounded Warrior Battalion-East was officially established. In 2010 the Camp Lejeune Fisher House opened its doors providing accommodations for families of recovering service members. A 100-room barracks was completed in 2011.

And in December 2012 a $29 million 37 000-square-foot facility called the Warrior Hope and Care Center was opened.

The center includes a fully equipped fitness center and physical rehabilitation area with a rock-climbing wall; a three-lane 25-yard lap pool; an underwater treadmill; a community area with a family lounge; and offices for medical case management recovery care coordinators transition services education specialists family support and chaplain programs.

“The intent of this building is to provide a one-stop shop for them ” Stephens says. “They can come here and see their recovery care coordinator participate in their WAR (Warrior Athlete Reconditioning) program see their medical case manager — it’s all right here.”

The facilities combine to provide the tools for the WWBn-E to carry out its mission of ensuring the best possible care for the wounded ill and injured service members and to help them prepare for life after the Corps.

“We have a good facility here ” says Kelley the battalion’s commanding officer. “We’re really responsible for coordinating the mind body spirit and family. We’re here to take care of the Marines first and foremost. We treat them with dignity we address their problems we help them as they transition.”

Marines are attached to the Wounded Warrior Battalion through a referral process. When possible less seriously injured Marines stay and recover with their units. But if their wounds are serious enough to require long-term specialized care or sufficient to lead to a medical discharge they become recovering service members. The acceptance rate of referrals is about 80 percent.

“If they need to be here they’re going to come here ” Stephens says. “We are not body-snatchers so we don’t go out to commands and grab people. But we will advocate with leadership that maybe this is the best place for them because of all the resources available.”

The Corps ethos can make it difficult to accept the assignment and not just because the dreams of a military career are shattered. For Marines used to being on the front lines and taking care of their comrades in arms on their right and left it’s often hard to admit they need help.

“They’re injured they’re broken a lot of them want to be out there with their fellow Marines that they deployed with and this is not the place they want to be ” said Sergeant Major Raquel Painter the senior NCO at WWBn-E before retiring in October. “When they get here they’re kind of hesitant or unsure. But when they see what is available to them and the difference that the resources we have make you’ll see the spark come in their eyes when they start planning for the future. That’s just an amazing thing to see someone that comes in broken and then they start their transition and they leave probably as whole as they could possibly be.”

Every Marine is surrounded by a team that includes a recovery care coordinator a medical case manager and a primary care manager. The team makes sure the Marines get every benefit they’re entitled to including any needed medical care at the Naval Hospital — about half a mile away — along with counseling job skills training and other resources.

“They got me into all these treatments ” says Chief Warrant Officer Brad Pottorff who was injured in Afghanistan in February of 2013. “There’s a TBI clinic my medical case managers my care coordinators. They put everything in a row and said ‘Here’s all your appointments this treatment is for you you need to go here and do this rehabilitation or therapy.’ They just put you on the right track. Not one single therapy is for everybody. There’s so many different things and this battalion has seen so many different cases of injuries. They know how to take care of you and if they don’t they’ll find you the help you need.”

The care revolves around four primary components.

“We focus on mind body soul and family ” Stephens says. “The mind is that transition piece what you can do while you are here. Let’s start leaning toward school let’s start leaning toward trade certification. The body let’s get you in the best possible physical condition. Spirit is what the chaplain does but it’s not just what the chaplain does. Its intent is to get that Marine Corps spirit back and the self worth. While we’re working on you we’re also working on the family putting it back together and maybe making it stronger.”

The body component includes the WAR program. Every Marine is required to participate in at least five hours of exercise a week including three hours of cardio activity.

“They were used to being athletic before they were injured ” Stephens says. “They’re used to going 100 miles an hour and they’re brought down to zero. Some of them enjoy zero a little too much so we get them involved in the WAR program. If they can’t run because of the injuries they can get into the pool. If they can’t get into the pool because they have an open wound they can come over here to the fitness center climb the wall do strength and conditioning just get them moving again. I had a Marine out on the tennis court a couple of years ago. It was the first time he’d been out since he was hit by an IED. Halfway through the match he pulled on his shirt and said ‘Look at me sir I’m sweating.’ It was the first time in about three years he’d been able to exercise to where he sweat. That was a big deal to him. That gave him the idea that ‘hey I can continue to do this.'”

The battalion also includes activities for families. Wives attend counseling sessions. Children stay at the Fisher House. Classes are available including workshops for expecting mothers.

“The same care and support I get is open to the family ” Pottorff says. “My wife has full access to the gym if she wants to come over and work out. She sits with me through my counseling and my appointments. There’s so much family stuff that goes on the luncheons the barbecues. Families are encouraged to come.”

A variety of treatments are available to the Marines including some non-traditional programs.

Craig Bone a wildlife artist who was injured while fighting in a civil war in Rhodesia in the late 1970s offers painting as a form of therapy (see Art Therapy in the November Wrightsville Beach Magazine). In a makeshift studio in the lobby of the Hope and Care Center he works with Marines to recreate historic scenes that depict everything from battles to tragedies. The art is donated to families or museums.

“It gets their minds off their problems ” Bone says. “They look forward to coming up. They are with their brothers and they’re useful. Being in battle is nothing compared to the battle when they get here trying to get their life in order and get moved out of the Marine Corps. They’re under a lot of pressure psychologically. When they come here to paint they just leave that behind for a couple of hours.”

Joan Farkas who is based at the Naval Hospital offers a different kind of art therapy. She invites Marines to paint masks that graphically depict the pain within.

“They paint demons scars things they’ve been through ” she says. “They are very powerful. It’s easier than talking. It’s like a mini-canvas. I’ve had some people really get elaborate with it. One guy’s has nails shooting out of it you see the stark eyes sometimes the mouth is completely gone because it’s hard to put it into words.

“This organizes what they are going through and they have an opportunity to express it.”

The length of stay for Marines at the Wounded Warrior Battalion-East is usually between eight and 18 months depending on where they are in the medical retirement process when they arrive. It never will be easy to take off that uniform for the last time but they have access to tools that make the transition easier.

“The battalion is not set up to take the lame the lazy and the injured across the Marine Corps ” says Capt. Andrew Yeary who was injured while serving as a tank commander in Afghanistan in 2012 and has been able to return to limited duty status. “It takes these wounded warriors and helps them focus on their recovery. It is a unit like no other I’ve been in in the Marine Corps. The only way you leave here not prepared for the next step in your life is if you don’t want to.”

Unseen Wounds

Between 10-18 percent of the 2.7 million veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have post-traumatic stress disorder according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Nineteen percent may have a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Seven percent have both. These injuries are not visible but can be just as debilitating as physical wounds.

TBI

A TBI is caused by a blow or jolt to the head or a penetrating head injury that disrupts the normal function of the brain. Victims can experience headaches sleep disturbance dizziness and balance problems nausea fatigue light sensitivity and ringing in the ears. They can have concentration and memory problems difficulty in finding the right words and are prone to irritability anxiety depression and mood swings.

PTSD

PTSD is triggered by experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event. Symptoms may include flashbacks nightmares and severe anxiety as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event. Those with PTSD may feel hopelessness shame or despair. Sufferers can experience anger and irritability. Depression anxiety and alcohol or drug use often occur.

“Wounded Warrior” is in the name of the Marine Corps regiment and battalion and a generic term for military members injured in service to their country. It is not an endorsement of any particular charitable organization. There are many non-profits that do fine work in support of our wounded heroes. Anyone motivated to donate to help these brave men and women should thoroughly investigate the organizations to ensure the most effective use of their money. Websites like charitynavigator.org are a valuable resource.

Brad Pottorff

Chief Warrant Officer USMC

Brad Pottorff is very matter-of-fact when he talks about the week that changed his life.

“I was injured in Afghanistan in February of 2013 ” he says. “I was diagnosed with TBI. I lost my hearing in my right ear and half the eyesight in my right eye. I had compressed vertebrae in my neck and my back from IED blasts and grenades.

“I was blown up five times in four days is what sums it up.”

Blown up. That’s the way Marines typically describe it. As though it’s no big deal. It’s part of being in the Corps of being on the front lines. War happens. You get blown up. You get shot. You deal with it and you move on.

Pottorff serving as a platoon commander expected to recover quickly and rejoin the fight. He soon recognized that he was wrong. His injuries were too severe.

“I realized that I was just short-changing the Marines that I had underneath me in my platoon ” he says. “I was failing myself and I was failing them. I accepted the fact that I wasn’t right I needed help.”

Pottorff arrived at the Wounded Warrior Battalion-East in May 2014.

“I came over here and started getting the treatment I needed ” he says. “They put me on the right track. I went through all the treatment and got to the point where I just made it back to full duty status.”

He can’t return to a combat unit but was assigned an operations job at the WWBn-E complex. He will retire in October after 21 years.

“My goal was I came into the Marine Corps full duty and I’m going to go out of the Marines Corps full duty ” he said.

Rosito Andaya

Staff Sergeant USMC

The plan was set. Rosito Andaya would join the Marines after high school stay in for four years and earn money for college. He would learn to be a diesel mechanic so if the college thing didn’t work he would have a trade.

Then a slick-talking recruiter with a chest full of medals rewrote the blueprint.

“He showed me his medals and badges ” Andaya says. “He said he was an infantryman recon. He said it’s going to be challenging but I thought I’m in shape. I run cross-country I play soccer. I was so na?ve. He sold it.”

Andaya switched to infantry and is still in the Marines 19 years later. He stayed through deployments to South Korea and Japan. He did tours in Haiti and Kosovo both combat deployments.

“I’ve seen some beautiful places ” he says.

Afghanistan and Iraq weren’t so beautiful. He sustained multiple blasts and has a compressed disc in his lower back. Marines in his unit under his care died. Friends who left the Corps have killed themselves. It’s not unusual. More than seven in 10 Marines personally know a fellow service member who has attempted or committed suicide.

“I started drinking heavily after coming back from Afghanistan ” he says. “My wife told me ‘Seek help or I’m leaving.’ I thought ‘There’s nothing wrong with me.’ Every Marine thinks they can handle it they don’t need help.”

Then another Marine buddy committed suicide. Andaya escorted the body home.

“That’s when I hit rock bottom ” he says. “I was drinking until I was blacking out in the garage. I finally realized I need help.”

Andaya was diagnosed with PTSD and is in the process of medical retirement.

“I’ll probably go back to school ” he says. “The main reason I wanted to go originally was so I could be a history teacher. I’m only 38.”

Andrew Yeary

Captain USMC

Andrew Yeary was a tank commander serving in Afghanistan when he was injured by an IED on October 16 2012.

“The good news is we were in a tank and survived ” he says. “The bad news is we were in a tank and survived. The tank is a flat bottom vehicle. When the blast goes up in a flat bottom we get the full brunt and we’re in a pretty tight tin can getting rattled around.”

Yeary sustained a lower back injury and a traumatic brain injury that caused complications with memory and focus along with headaches and vision problems. He was seriously wounded but had a hard time acknowledging it.

“I didn’t want to stop being a Marine or be labeled a wounded warrior ” he says. “I tried to push through. I wanted to operate at the same level as I did before but I couldn’t. The first step was admitting that I needed further medical treatment.”

Although he couldn’t operate at the same high level as a Marine it was anger issues caused by his TBI that manifested at home that provided the needed wake-up call.

“I would get so mad over the littlest things ” he says. “It was all verbal and yelling. It embarrassed me and I knew something was going on. It finally took my wife saying ‘This is not the way it’s supposed to be. Your kids deserve better.’ She put it in perspective.”

He arrived at WWBn-East in November 2013. Nine months later he was assigned a staff job at the battalion. He can no longer be a tank commander but being on permanent limited duty gives him a chance to make it to the 20-year retirement mark in a couple of years.

“That is definitely my goal ” he says.

David Leibenguth

Gunnery Sergeant USMC

After serving on the front lines in Iraq life back in the States can seem too slow-paced.

“When I deployed I liked to get shot at ” David Leibenguth says. “I’m weird. I like the rush. I’ve been bored.”

Leibenguth looked for ways to replicate the thrill. That’s why when he was sent to the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms California he spent some free time in downhill speed skating.

“I was wearing all of the proper gear ” he says. “But I ran into a pillar going about 50 miles an hour.”

He already was dealing with PTSD from serving two tours in Iraq in 2005 and 2006. Now he had a fractured femur.

The Wounded Warrior Regiment exists to take care of wounded ill and injured Marines regardless of how the injury occurs. Leibenguth was sent to the Wounded Warrior Battalion-West at Camp Pendleton where he underwent surgery and had a rod inserted in his leg.

He’s since been transferred to WWBn-E at Camp Lejeune. He had a second operation because of complications with the rod and is in the medical retirement process.

“I’m trying to get back to the fleet ” he says. “It all depends on my leg. But worse case scenario I’ll move on.”

If he has to separate his time at the Wounded Warrior Battalion has helped prepare him for life outside the Corps.

“I was go go go ” he says. “I was so wired. They taught me to deal with the stuff I’m dealing with. It’s helped me slow down spend time with my boy. I was never home and now I’m able to coach his football games.”

Richard Ung

Sergeant USMC

The duty assignment to Wounded Warrior Battalion-East was difficult to accept. Richard Ung wanted to be on the front lines not in a facility for wounded injured and ill Marines.

“My battalion just handed me a checkout sheet and told me that they wanted me to get better ” Ung says. “They said I’ve done my part for the Marine Corps and now it’s time for the Marine Corps to take care of me.”

Ung was seriously injured by an IED explosion in Iraq in 2011. His nose and thumb were fractured. He was diagnosed with a TBI. But it was difficult to admit he was hurt enough to need long-term treatment or to leave the Corps.

“You’ve always been taught throughout your whole career that you are almost indestructible ” he says. “You come from a long line of other Marines that have done great things. When you wear this uniform you wear the same pride that they wear. You don’t ever want to let them down. Admitting that you are sick or you are injured is hard.”

Even in the midst of the medical retirement process it’s still hard for the eight-year veteran.

“I’m kind of fighting to go back ” he says. “I actually wanted to be a combat instructor to teach Marines how to fight and tap into my knowledge.”

But the reality is Ung will separate from the Corps soon and step into an uncertain future.

“I had a dream to become a pilot when I got out of the Marines Corps ” he says. “I thought I was going to do my tours and get out and go to flight school and become an airline pilot. Having a traumatic brain injury closed that door for me. I lost two dreams with one incident.”

Julian Bejarano

Sergeant USMC

It was no big deal the first time Julian Bejarano was blown up.

“I didn’t really say anything except my head hurts ” he says.

The same thing for the second time. And the third fourth and fifth. When you are a mortarman in the U.S. Marine Corps serving on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan you don’t let injuries or headaches — or even undiagnosed PTSD — slow you down.

“I was having issues with a lot of things ” he says. “I lost a lot of my friends a lot of my Marines. But I still didn’t say anything. We’re always taught to push through. If you’re cold you push through it. If you’re hungry you push through it. It becomes a part of who we are.”

The sixth time was different. He was coordinating air support for a resupply convoy in Helmand province Afghanistan in July 2013 when an IED detonated near his mine resistant ambush protected vehicle (MRAP). The blast picked up the big armored vehicle and flung it on its side.

“It gave me a really bad TBI and messed up my neck and back pretty bad ” he says. “I came home and I was still having issues. I was making breakfast for my daughter and my wife one day and I passed out in the kitchen.”

The accumulated mental and physical injuries had taken a toll. Bejarano an 11-year veteran could no longer serve in combat.

“They told me I’m unfit for duty because of the injuries ” he says. “I had planned on making the Marine Corps my career staying in the rest of my life.”

Bejarano isn’t certain what he will do next but his path might lead to Wilmington.

“Cape Fear Community College has a boat-building program ” he says. “I have a thing for wooden boats so I think I’m going to get into that.”