Singing History Loudly

BY Simon Gonzalez

Cleve Callison was hosting a show of eclectic music at a public radio station in Huntsville Alabama in the late 1970s when he found an album of something called Sacred Harp singing in the library.

“I had never even heard of it ” he says. “I put it on the air not even having previewed it. I made the comment after I had played a song or two ‘That’s the strangest music I’ve ever heard.'”

Sacred Harp music indeed is strange to ears accustomed to well just about anything else.

“It’s a very unique sound ” says Gill Minor a member of a group of Wilmington Sacred Harp singers. “I don’t think there’s anything quite like it.”

Even those who participate have a hard time describing it.

“The harmonies are different than we’re used to ” Pamela Minor says. “There are more open chords and some unusual chords which gives a kind of eerie sound to things. There are no dynamic markings so people tend to sing pretty loud. That’s what makes it so exhilarating though. Exhilarating. That’s the best word I have for it.”

Eerie and exhilarating is one of many seemingly contradictory couplets that have been used to describe Sacred Harp singing.

It is austere yet hauntingly beautiful. Sacred and secular. Gloomy and joyous. Incoherent and profound. Sung and shouted. Difficult to learn and easy to put into practice. Simple and complex. Nearly dead and reborn. Performed publicly but without an audience. Loud and … louder.

“It can sound very different ” Callison says. “It’s so unusual a lot of people find it too strange.”

Sacred Harp is a form of shape-note singing a type of music that dates back to American Colonial times. Unlike traditional seven-syllable scales it only has four notes: fa sol la and mi. The tunes are written in standard notation but the notes appear in shapes: triangle oval rectangle and diamond.

The shapes were created around 1790 to make it easier for people to sing hymns and sacred songs. Itinerant instructors and songwriters traveled from place to place using the system to teach sight-reading to people without formal music training.

Shape-note singing began to fall out of favor in New England when the musical elitists of the day preferring the seven-note system began to look down their noses at this crude uncouth primitive method. But even as it diminished up North it took root in the rural South.

In 1844 a songbook called The Sacred Harp was published in Georgia. The work has been published in multiple editions since and is used by singers today.

The singings are a cappella so the name is a bit of a misnomer.

“Most people say the title refers to the human voice as an instrument ” Callison says.

Callison learned all about the history of the music and much more after playing the album on his radio program all those years ago. After making the remark about the strangeness of the sound his phone began to ring.

“All of a sudden I started getting all these phone calls from people who were saying that you realize you are living in the heartland of Sacred Harp music ” Callison says. “I had no idea. I didn’t know anything about it. These people invited me to come to a singing. They would have all-day singings sometimes all-weekend singings at churches.”

At the singings the participants arrange themselves according to their voices on four sides of a hollow square. The tenors face the altos and the basses face the sopranos. The leader stands in the middle and keeps time. There are few if any spectators. Everyone is expected to sing. The melody is carried by the tenors unlike in traditional choral music where it’s in the soprano line.

The lyrics are sacred often hymns that date back as early as the 1600s but singers outside the Christian faith are drawn to the music. Lyrics can deal with weighty matters — sin and death sorrow and loss — but are sung boisterously.

Callison was intrigued. He attended another singing in Georgia and produced a documentary that aired on National Public Radio’s Options series in October 1979. The documentary won “Best Radio Program” from the Southern Educational Communications Association in 1980.

The program did more than win awards. It also made Callison a Sacred Harp singer.

“People are interested in authenticity ” he says. “This touches something deep.

There’s a sense of community of sharing an experience. It puts you in touch with that American 18th-century rugged individualism ethos. It’s plain and unadorned like Shaker furniture.”

His program aired during a period when Sacred Harp music was enjoying resurgence after nearly disappearing in the 20th century. The once-vibrant art form was confined to small rural churches in pockets of Georgia northern Alabama and western North Carolina. In the late ’70s it was discovered by folk music aficionados and began to move back outside the South. The music appeared in the movie “Cold Mountain” in 2003 and in 2006 a feature documentary called “Awake My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp” aired on Public Television stations nationwide raising more awareness.

“Today there are singings in every state with huge ones in Chicago and Washington D.C. and in several foreign countries ” Callison says.

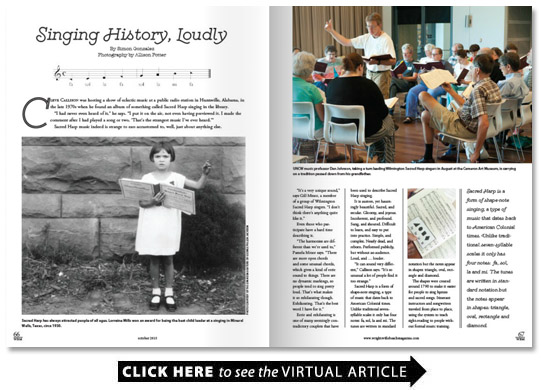

There is even a small but dedicated group of Sacred Harp singers in Wilmington meeting the last Sunday of most months at the Cameron Art Museum.

Callison brought his love for the music to the North Carolina coast when he became station manager at Wilmington public radio station WHQR in 2010. He attended singings in the Raleigh-Durham area but hoped for something closer to home. A couple of years ago the museum agreed to air “Awake My Soul” and host singings.

“Sacred Harp singing affords an opportunity for people to come in and participate ” says Daphne Holmes the museum’s curator of public programs. “It’s social singing. It’s something for the community.”

The group has a core of 12-15 singers. During the August event singers from the Raleigh-Durham area helped swell the numbers to over 30.

Large or small singings at the CAM mirror those that take place at any gathering in the country or around the world. A leader moves to the middle of the hollow square and calls a song. The group democratically decides on a key — “It’s a key of convenience ” Callison says. They begin by singing the notes the first time through before switching to the words.

Hearing “fa sol sol mi la la” instead of words can sound like gibberish but the aesthetics of the melody are present along with the vigor and the volume level. Faster tunes are almost shouted rather than sung.

“It’s extremely energetic ” Callison says. “There’s not much subtle about it. It’s almost like an aerobic workout. Some songs are done at breakneck speed. Loud is good. Louder is better.”

That’s what drew Rachel Mann to Sacred Harp music about 15 months ago.

“It’s loud and boisterous ” she said. “It’s fun.”

Mann is a former church organist and very familiar with the demanding critical rehearsal-oriented nature of more formal choral music. She finds Sacred Harp to be a refreshing change.

“It’s just the fun and the camaraderie ” she says. “Everybody participates. You can mess up here and nobody cares.”

Dan Johnson also appreciates that participation is encouraged regardless of ability.

“We have all these shows like ‘American Idol’ that are looking for the best singers ” he says. “This is much more inclusive and self-expressive.”

Johnson a professor of music and music education at University of North Carolina Wilmington began singing in New England in 1995. His grandfather was a Sacred Harp singer and Johnson uses his book.

“It’s one of the traditional American folk music forms ” he says. “It combines the traditions of sacred and secular music.”

Every singer has a story about what attracted him or her to the music. For Pamela Minor it was the lyrics. She first encountered shape-note music in upstate New York when she saw a performance while attending a fair with her sister. Then she discovered that there were Sacred Notes singings near her mother’s home in Alabama on any given weekend and she began to attend during visits back home.

“I found it very moving ” she says. “There’s one particular song that’s called ‘David’s Lamentation.’ It’s quoting when his son Absalom dies. ‘O Absalom My Son My Son.’ This is four-part harmony all a cappella and loud. I was just so moved.”

Pamela’s husband Gill appreciates that the tradition has been handed down through the generations.

“There’s certainly an appeal to this being a part of our heritage in American culture ” he says. “There’s a history to it. That part of it plays into it. This tradition has been going on and maintained and preserved in the South.”

Gill Minor didn’t join his wife as a Sacred Harp singer until two years ago when Callison formed the Wilmington group.

“I am not a singer nor do I consider myself one ” he says. “I don’t read music formally but the shaped notes made it easier to follow along. I enjoyed being able to sing in a group of people who didn’t care how good or bad I was. They were just glad to have my presence to sing these songs.”

That fits into the Sacred Harp tradition that anyone can sing. They might have difficulty learning the shapes. They might find it incredibly simple or needlessly complex. They might think it sounds strange. But they will be welcomed and encouraged to participate. Loudly.

“It’s music sung by ordinary folks for pleasure and worship ” Callison says.