Originally published in the July 2016 issue of Wrightsville Beach Magazine.

The story begins in 1857, with the final voyage of the SS Central America.

The 280-foot side-wheel steamer was carrying nearly 600 passengers and crew when she sank in a hurricane about 160 miles off the Carolina coast. It was America’s worst peacetime sea disaster, with 425 lives lost. But what captured the public’s imagination was the gold. Up to 21 tons of it, mined in the waning days of the California Gold Rush.

The ship remained lost for well over a century, on the ocean floor about 7,000 feet below the surface.

In the early 1980s, new technologies in sonar and undersea operations made recovery at least theoretically possible. Tommy Thompson, an engineer working at Battelle in Columbus, Ohio, put together a crew and raised the needed capital.

The Columbus- America Discovery Group used computer models to predict where the Central America might be and employed side-scan sonar technology to scan a 1,400-square-mile section of the ocean floor.

Unscratched freshly minted, uncirculated gold coins were worth approximately $4,000 each at the time of the discovery.

In 1987, after 100 days at sea, they found the SS Central America.

While searching for the wreck, the adventurers were supplied by a seaplane based out of Air Wilmington, the private plane terminal located at Wilmington International Airport.

At first, Air Wilmington president Bill Cherry didn’t know the seaplane belonged to a group hunting for lost treasure.

“They were very tight-lipped,” Cherry says. “We were just told it was ocean research.”

The group also needed a berth for a supply boat, and Cherry pointed them to Seapath Yacht Club and George Bond at Wrightsville Beach.

“The supply boat stayed there on the outer dock,” says Bond, the former general manager at Seapath.

Even if he didn’t know that Thompson and Co. were looking for the famous ship of gold, Cherry did get word of some of their cutting-edge technology.

“That was the first time I had even seen or heard of Global Positioning System (GPS),” he says. “They were renting it from the federal government. They did some magnificent tracking to find out where the wreck was.”

The aircraft used during the search phase was a single-engine Seabee floatplane. After a few months, the original pilot was replaced by Lance McAfee, who brought in a larger Piaggio P. 136 L1 Royal Gull seaplane.

Like many on the team, he took the job without knowing all the details.

“I was not fully briefed,” he says. “They didn’t say it’s a shipwreck. I was told it was a deep ocean research project. It might have been a month or two before I had the pieces put together.”

When he was told the true object of the research, McAfee wanted to make sure the focus would be in the right place.

“The party line — and I truly accepted it and embraced it — was we did not want the term ‘treasure hunter’ used,” McAfee says. “We were doing research. The shipwreck was a huge human tragedy.”

McAfee would fly equipment out to the Arctic Discoverer, a 180-foot fishing boat outfitted as a research vessel that would be at the wreck site for up to one month at a time.

“It was spare parts, cigarettes, toothpaste, mail and magazines, and ‘please God bring us a new movie,’” McAfee says. “I would take it out in the seaplane and drop it.”

It wasn’t a high-tech delivery. The supplies were put in sealed barrels that could float.

“From takeoff to the ship was a touch under two hours,” McAfee says. “We’d prop the door open and what I called my bombardier would pitch the stuff out. I would get 20 feet off the water, door open, flaps down, stall warning screaming. As he was throwing it out, I would be making the turn to come back for the second run.”

Food and bulkier supplies were taken out on the 56-foot aluminum-hulled boat that was docked at Seapath Marina.

Keeping the Arctic Discoverer over the wreck site was another technological achievement.

“They tied the nav into the ship and had two engines that could pivot,” Cherry says. “They developed a propulsion system that would hover over the wreck for a month at a time. That was the brilliant part of it. It was quite a scientific undertaking.”

Thompson’s team also designed and built a remotely controlled submersible they called Nemo that was capable of delicate, intricate work and performing precise tasks thousands of feet below the surface. Nemo recorded more than 1,000 hours of bottom time between 1988 and 1991, recovering gold and historic artifacts. The team even discovered a new species of deep-sea octopus.

McAfee remembers when he got word that the first of the gold was brought up.

“That was an exhilarating, exciting moment,” he says. “We had proof that we were on a shipwreck with gold on board, and had the capability to recover it.”

The thrill was more about the accomplishment than the treasure.

“The cool moments were when we developed new technology for the robot and saw it work,” McAfee says.

But it was the gold — flakes, lumps, coins, ingots — that made the headlines. Life magazine called it “the greatest treasure ever found.” People magazine described Thompson as “the kind of guy who could fix a rocket ship with two paper clips and a piece of twine … a genuine America hero.”

Cherry got to see the gold when he was invited to a public exhibit in Norfolk, Virginia.

“It was quite impressive,” Cherry says. “I’d never seen that much gold. You’d see everything from a little flake to a huge gold bar.”

As millions of dollars’ worth of gold was recovered, legal challenges followed. A group of American and British companies that had insured the ship’s cargo more than a century ago claimed rights to the treasure. The work halted.

While the fate of the treasure was tied up in court, many on the crew wanted to take their technology and scientific achievements and apply them to other wreck sites. But McAfee says Thompson became sidetracked by the thought of books and movies, succumbing to the fame monster if not the greed monster.

“We had so many opportunities to develop technologies,” McAfee says. “They hated it when I got on the phone during a conference call and said, ‘We are a diving company, let’s go dive.’ I didn’t care about potential movies or books or exhibits.”

A group of investors sued Thompson in 2005, claiming they had not received the returns they were promised. He dropped out of sight. The treasure hunter had become a fugitive. In 2012, he missed a hearing related to the suit by the investors and an arrest warrant was issued.

Thompson evaded capture until 2015, when he was arrested in a Florida hotel. He next languished in jail in Delaware County, Ohio, held in contempt for refusing to answer questions about missing gold coins. Other court battles continue.

It’s uncertain just how much gold was recovered. Reports variously estimate the haul from $300 million to $500 million. There’s speculation that as much as $97 million more remains on the ocean floor.

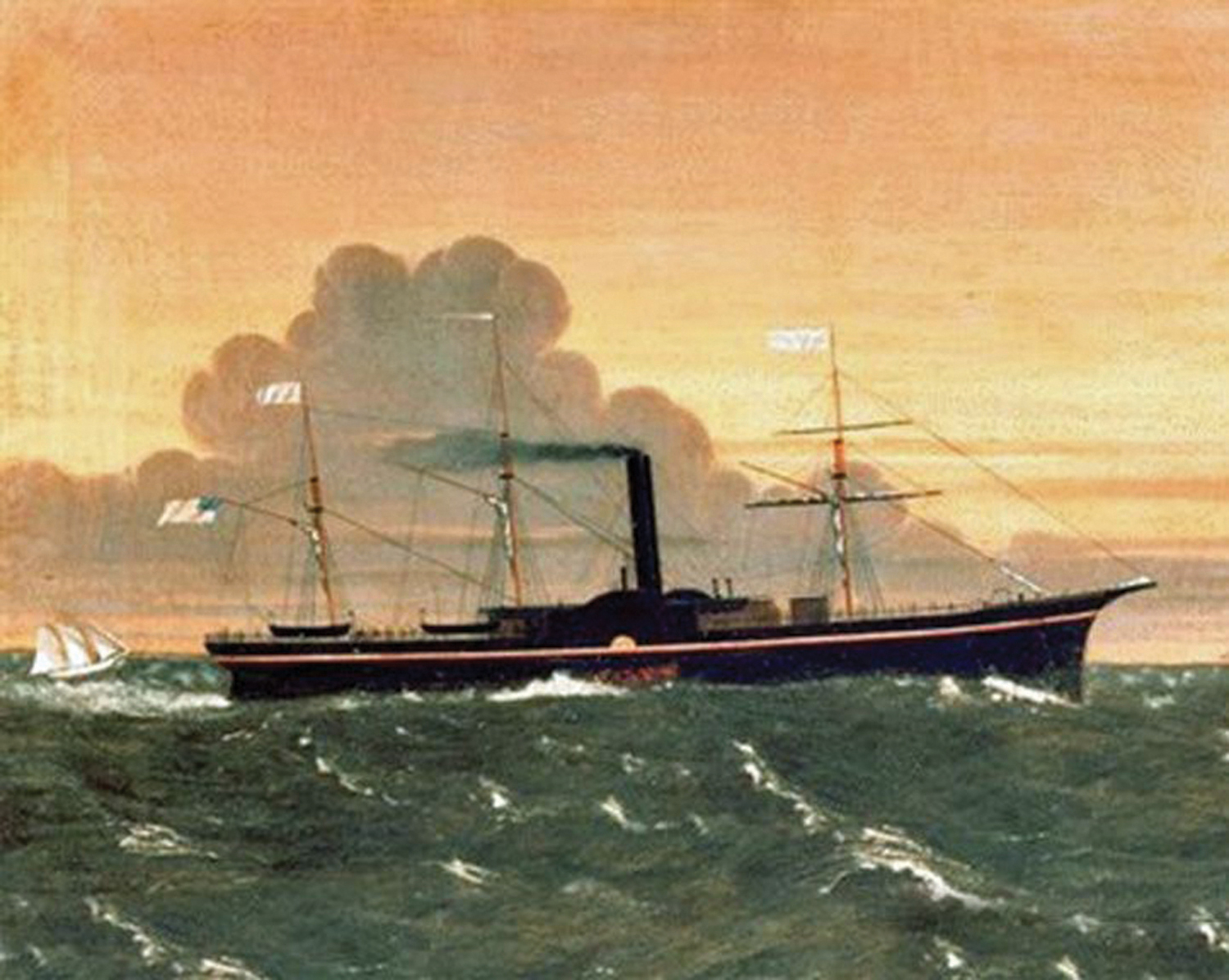

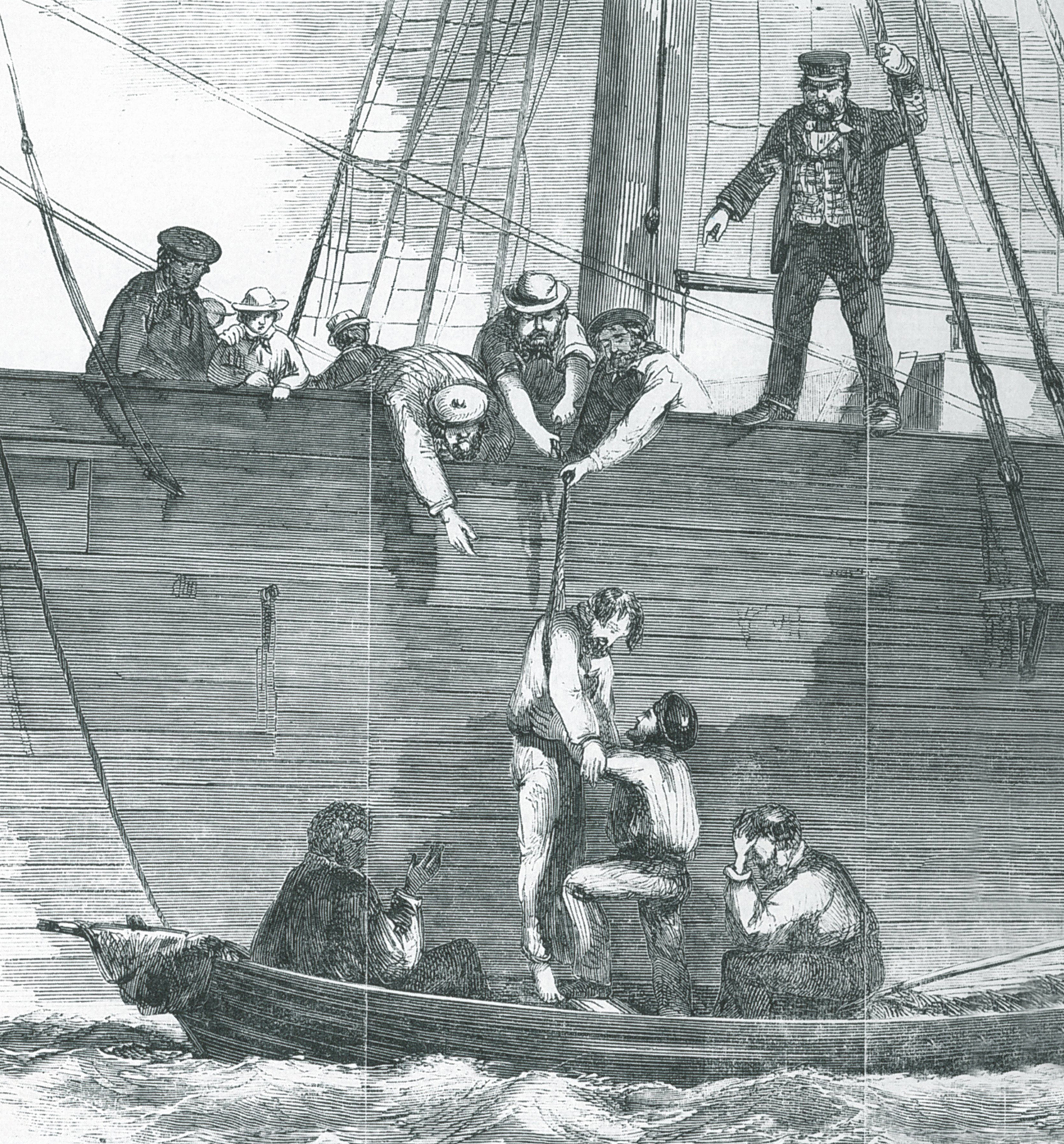

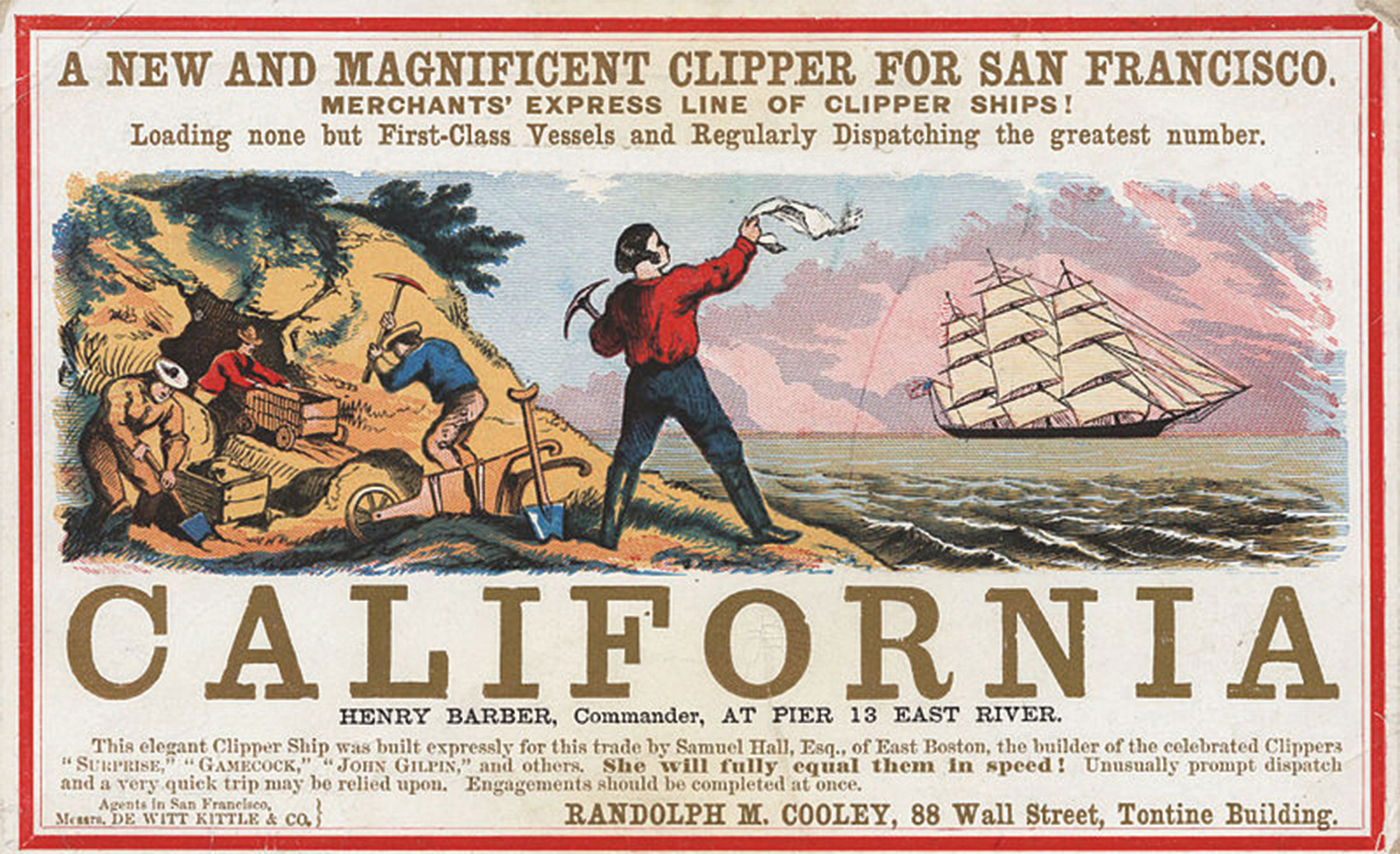

Top left and center: SS Central America’s captain, William Lewis Herndon, went down with the ship. Top right: Herndon’s daughter, Ellen, married Chester Arthur who became the 21st president of the United States. Bottom left: Above, left: Painting of the Central America. Above, center: Engravings from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 17, 1857. Above, right: A sailing card for the clipper ship California, depicting scenes from the California gold rush.

The Sinking of the SS Central America

THE SS Central America was a mail ship, part of a fleet of sidewheel steamers built to connect the new Territory of California with the rest of the country at a time before the completion of the transcontinental railroad, when there was no overland route from the East Coast.

The steamships carried mail, newspapers, freight and passengers. After the discovery of gold in 1848, they also transported tons of the precious metal.

On Sept. 3, 1857, the 280-foot ship left the port of Aspinwall (now Colón) under Commander William Lewis Herndon, a U.S. Navy Captain, with 477 passengers, 101 crewmembers, 38,000 pieces of mail, and tons of gold.

The ship encountered a category two hurricane off the Carolina coast. Huge waves swamped over her sides. Passengers and crew bailed all night, fighting against the rising water. It was no use. The ship was sinking.

In total, 425 perished, including Herndon, who went down with his ship. Survivors said that at the end, Herndon was in full uniform, standing by the wheelhouse with his hand on the rail, hat off and in his hand, with his head bowed in prayer.

He was considered a hero for his efforts in trying to save the ship, and in his actions in loading the passengers into lifeboats. Two U.S. Navy ships were later named USS Herndon in his honor, as was the town of Herndon, Virginia. Two years after the sinking, his daughter Ellen married Chester Alan Arthur, but she died of pneumonia before he became the 21st president of the United States.