Rails & Tides

BY Phillip Bryant

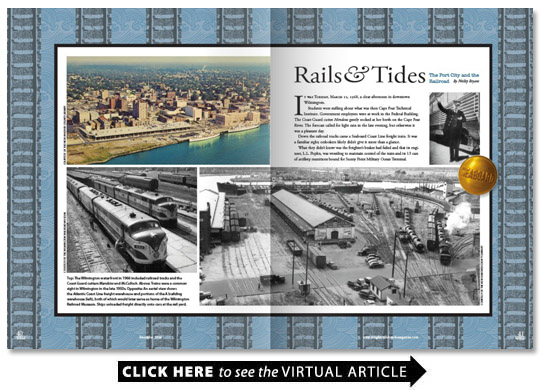

It was Tuesday March 12 1968 a clear afternoon in downtown Wilmington.

Students were milling about what was then Cape Fear Technical Institute. Government employees were at work in the Federal Building. The Coast Guard cutter Mendota gently rocked at her berth on the Cape Fear River. The forecast called for light rain in the late evening but otherwise it was a pleasant day.

Down the railroad tracks came a Seaboard Coast Line freight train. It was a familiar sight; onlookers likely didn’t give it more than a glance.

What they didn’t know was the freighter’s brakes had failed and that its engineer L.L. Poplin was wrestling to maintain control of the train and its 13 cars of artillery munitions bound for Sunny Point Military Ocean Terminal.

The train was moving at around 30 mph when Poplin bailed out as it passed Front Street. The freighter continued on without him ramming the parked boxcars at the end of the dock setting off into the waterfront and crashing into a docked Gulf Service oil tanker piercing the starboard hull.

There were no injuries and more miraculously the cars with the artillery shells remained on land. There was no explosion.

Witnesses remarked that it was the day “a train tried to sink a ship.” Instead the ship remained afloat and it was the locomotive that sunk disappearing below the surface of the Cape Fear River.

The train disappearing beneath the murky waters was both ironic and symbolic. The railroad once reigned supreme in Wilmington. By the late ’60s it was virtually sunk.

Nearly a year before the accident the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad had formed as the result of a merger between two rivals: the Seaboard Air Line and the Atlantic Coast Line. The latter had been a hub of Wilmington commerce for generations the apex of the city’s long and storied history with the locomotive. But the ACL had left Wilmington — its home since 1900 — at the beginning of the decade moving its headquarters to Jacksonville Florida.

Much of American history of the 19th and 20th centuries runs parallel to the history of its railroads. In much the same way to study the history of Wilmington its commerce and its people is to study the Atlantic Coast Line.

In the early 19th century facing economic challenges from Virginia and South Carolina North Carolina community leaders began exploring ways to cement the region’s trade importance. Their primary goal was to construct a railroad from Raleigh to Wilmington connecting the state’s capital and its principal port city.

After years of attempted fundraising the Raleigh end fell through. The railroad detoured north to Weldon North Carolina where it could connect to a line that led to Petersburg Virginia. It was operational by 1840. Two engines the New Hanover and the Brunswick made the 161-mile-long trip — at that time the longest rail line in the world. In 1855 the name officially changed from the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad to the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad.

By the late 1860s Wilmington was the center of a railroad network that extended like veins all across the state and beyond. Goods flowed in and out of the Port City not just on the W&W but also the Wilmington Charlotte and Rutherford Railroad (WC&R) to the west and the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad (W&M) which ran down to South Carolina.

By the turn of the century the WC&R would morph into the Seaboard Air Line while the W&M consolidated with the W&W would form the central stretch of the Atlantic Coast Line.

Before the birth of the ACL the railway nearly died. Railways became prime military targets with the advent of the Civil War in 1861. As the war wound down Wilmington and its railroads held the last breaths of the Confederacy. During the final months of the war chunks of the W&W were destroyed and with that came the beginning of the end for the South.

“By August of 1864 Wilmington was the last Southern seaport still open to trade with the outside world ” says Dr. Chris Fonvielle University of North Carolina Wilmington professor historian and author of “The Wilmington Campaign: Last Days of Departing Hope.” “By then only Virginia North Carolina and South Carolina remained in Confederate control. General Robert E. Lee sent word to military authorities in the then-Department of the Cape Fear saying “If Wilmington falls I cannot maintain my army.”

“So the fate of the Confederacy which depended upon the survival of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia depended upon Wilmington remaining open to the blockade-running trade with Europe especially Great Britain ” Fonvielle says. “The Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was considered ‘Lee’s Lifeline’ and the ‘Lifeline of the Confederacy’ by then. It was no accident that 42 days after Wilmington fell to Union forces on February 22 1865 Lee surrendered to U.S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse Virginia.”

It’s difficult to calculate the role the railroad played in the war in terms of moving troops and supplies where they were needed or in staving off defeat by transporting goods from blockade runners. Just as the railroads and its surrounding structures were destroyed so then over time were important records.

“Quantifying the importance of and extent of trade along Wilmington’s railroads during the Civil War has been a most challenging subject for historians ” Fonvielle says. “Unfortunately the District of the Cape Fear records 80 linear feet worth were burned by the local district’s U.S. Corps of Engineers during the early 1980s. It was a shame that the documents survived for more than 125 years only to be indifferently disposed of by a U.S. government agency.”

While the Civil War damaged the railroad industry in the South it was the post-conflict reconstruction that revived and strengthened it. Rebuilding was underway promptly and it was this effort to lay new track across the state that led to the Atlantic Coast Line’s official formation.

After some financial backing from Baltimore the W&W railroad was at full capacity by the 1870s under the leadership of Robert R. Bridgers. By the 1880s an idea was forming to create a single entity rail line that would transport passengers and cargo from the Northeast down each port on the Coast even rounding the Gulf into New Orleans.

The Atlantic Coast Line was first an unofficial title that passengers and engineers gave the interconnected but independent rails by which they traveled down the coast. Then in 1900 the ACL was formally created as a corporation a consolidation of the many railways that tracked the Eastern Seaboard.

A crucial section was still missing. Florida businessman Henry Plant owned most of the lines that ran from Charleston South Carolina to Savannah Georgia and down into the southern points of Florida. After Plant’s death in 1902 his heirs sold his holdings to the ACL.

The addition of Plant’s railways increased the Atlantic Coast Line’s rail miles by 2 235 making it a true coastal line.

Wilmington remained the headquarters. For nearly 60 years every Wilmingtonian knew someone who worked for the ACL.

“During this period the railroad was the largest employer in the city and its primary industry ” says Mark Koenig executive director of the Wilmington Railroad Museum.

From its formal inception in 1900 the ACL was a through line for the first half of the 20th century in Wilmington. It experienced rapid growth in the 1920s double-tracking most of its routes and opening new terminals in Richmond Virginia and Jacksonville Florida. The Jacksonville terminal alone processed more than 20 000 passengers daily.

During the Great Depression the company’s freight service was cut almost in half but it avoided bankruptcy in one of the few periods the railroad ever recorded financial losses.

In the 1940s the ACL experienced its golden age. Champ McDowell Davis took over operations as president in 1942. Davis had worked for the railroad since its infancy first as a messenger boy in 1893 for the W&W then at various management positions until his ascension to the head role.

Davis was esteemed as perhaps the most powerful and influential figure in Wilmington during his presidency. Koenig describes his tenure as “the defining story of the Atlantic Coast Line.”

Davis retired in 1957 after working at the same company for almost 64 years.

Two years earlier in 1955 the ACL announced that it would transfer its headquarters to another city. The date of the announcement December 15 would come to be known as Black Thursday for the economic effects the relocation would have on the region.

Wilmington had survived the Great Depression in large measure because of the Atlantic Coast Line but would for decades experience its own economic downturn in its absence.

By the time the move was complete more than 900 families employed by ACL would relocate to Jacksonville Florida. The corner of Red Cross and Front streets which for generations had stood as an epicenter of eastern locomotives was now just another stop on the Atlantic Coast Line.

Champ Davis fought relentlessly with the board of directors over the proposed move but was ultimately defeated. His story with the railroad ends in melancholy: he was reported to have resigned all his many railroad associations and to have sold all of his stock in the company. He refused a position on the same board of directors that had thwarted his efforts to keep the headquarters in Wilmington.

Instead Davis in remembrance of his mother developed a passion for the elderly and later founded the Cornelia Nixon Davis Nursing Home which evolved into the Davis Community an assisted-living facility in Porters Neck. Upon his death in 1975 his ashes were scattered around a flagpole on the grounds.

Davis’s story is told in earnest at the Wilmington Railroad Museum located downtown at 505 Nutt Street and housed in an authentic 1883 freight warehouse. The mission of the museum Koenig says “is to educate illustrate and demonstrate” the history of Wilmington’s railroads in particular the Atlantic Coast Line.

The education and illustration is apparent in the many exhibits and artifacts but its demonstration is what really puts the importance of the ACL into context. The entire back room of the museum houses an extensive model of the Atlantic Coast Line circa the 1960s stretching through miniature towns like Selma North Carolina all the way to Wilmington’s downtown all realized in extraordinary detail.

It is a reminder of the pinnacle of American transportation. To stand in the recreated freighter train is to stand inside a behemoth of metal and iron and steam. And though the Atlantic Coast Line is an artifact of another time it is not altogether gone.

After the initial merger to form Seaboard Air Line in 1967 further consolidation would create the Family Lines then the Seaboard System Railroad. In 1986 the Seaboard System and the Chessie System would merge forming CSX. This summer the railway transportation company announced plans for a new transportation hub in New Hanover County that will connect the Port of Wilmington with Charlotte.

Perhaps that freighter when it plunged into the water wasn’t trying to sink a ship. Maybe it was just a runaway trying to return to the Port City.