Port City POWs

BY Katie Meine Aurelia Colvin Ella Forkin and Audrey Dahl

In 1943 The Allied North African Campaign of World War II was successfully concluding.

Following victories versus the Axis powers the British and Americans took more than 500 000 German and Italian prisoners. Without room in England for the massive number of prisoners camps to house the sudden influx were hastily established throughout the United States. Most states had prisoner of war (POW) camps during World War II but the southern U.S. was preferred since less money had to be spent for land labor and heating costs. As a result thousands of German soldiers were sent to camps throughout North Carolina including the port city of Wilmington. From 1943 to 1946 Wilmington was home to three prison camps. In all Wilmington housed more than 500 Axis prisoners.

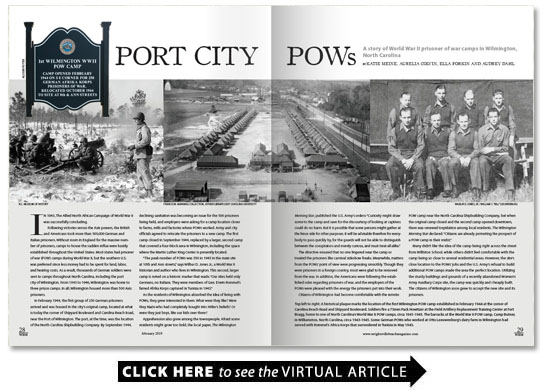

In February 1944 the first group of 250 German prisoners arrived and was housed in the city’s original camp located at what is today the corner of Shipyard Boulevard and Carolina Beach Road near the Port of Wilmington. The port at the time was the location of the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company. By September 1944 declining sanitation was becoming an issue for the 500 prisoners being held and employers were asking for a camp location closer to farms mills and factories where POWs worked. Army and city officials agreed to relocate the prisoners to a new camp. The first camp closed in September 1944 replaced by a larger second camp that covered a four-block area in Wilmington including the space where the Martin Luther King Center is presently located.

“The peak number of POWs was 550 in 1945 in the main site at10th and Ann streets ” says Wilbur D. Jones Jr. a World War II historian and author who lives in Wilmington. This second larger camp is noted on a historic marker that reads: “Our sites held only Germans no Italians. They were members of Gen. Erwin Rommel’s famed Afrika Korps captured in Tunisia in 1943.”

As the residents of Wilmington absorbed the idea of living with POWs they grew interested in them. What were they like? Were they Nazis who had completely bought into Hitler’s beliefs? Or were they just boys like our kids over there?

Apprehension also grew among the townspeople. Afraid some residents might grow too bold the local paper The Wilmington Morning Star published the U.S. Army’s orders: “Curiosity might draw some to the camp and save for the discourtesy of looking at captives could do no harm. But it is possible that some persons might gather at the fence side for other purposes. It will be advisable therefore for everybody to pass quickly by for the guards will not be able to distinguish between the conspirators and merely curious and must treat all alike.”

The directive ensured that no one lingered near the camp or treated the prisoners like carnival sideshow freaks. Meanwhile matters from the POWs’ point of view were progressing smoothly. Though they were prisoners in a foreign country most were glad to be removed from the war. In addition the Americans were following the established rules regarding prisoners of war and the employers of the POWs were pleased with the energy the prisoners put into their work.

Citizens of Wilmington had become comfortable with the remote POW camp near the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company but when the original camp closed and the second camp opened downtown there was renewed trepidation among local residents. The Wilmington Morning Star declared: “Citizens are already protesting the prospect of a POW camp in their midst.”

Many didn’t like the idea of the camp being right across the street from Williston School while others didn’t feel comfortable with the camp being so close to several residential areas. However the site’s close location to the POWs’ jobs and the U.S. Army’s refusal to build additional POW camps made the area the perfect location. Utilizing the sturdy buildings and grounds of a recently abandoned Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps site the camp was quickly and cheaply built. The citizens of Wilmington soon grew to accept the new site and its prisoners.

The third camp located at Bluethenthal Field or what today is Wilmington International Airport was on the outskirts of town and held fewer prisoners.

“The camp at Bluethenthal Army Air Field was a small satellite site where POWs worked in the laundry mess hall in lawn maintenance and in other labor roles ” Jones says. In his book “A Sentimental Journey: Memoirs of a Wartime Boomtown “Jones interviews some local Wilmington residents including Peggy Moore Perdew who recalls the Germans “had free run of the air base raking leaves and doing chores — pretty funny to see them ambling around no one seemed to be supervising.”

The prisoners eased the labor shortage by harvesting crops and working at fertilizer plants pulpwood mills and dairies. Some were afraid of the foreign soldiers and the anti-Nazi propaganda reinforced these fears in both adults and children.

Jones also interviews Margaret Sampson a child during the war and a student at Williston Primary and Industrial School. She remembers the fear and recalls how she was taught by teachers to climb a tree in case of a prison break. Though her teachers were apprehensive about the Germans the schoolchildren were curious about the new residents across the street from their school.

“We’d dash across the street and give them candy and gum and talk to them. A lot of the times we couldn’t understand them but the gestures were friendly ” Sampson tells Jones.

Katherine Byars another Wilmington native also remembers the prisoners as amiable.

“They would wave back at us you know. They were friendly and probably would have liked to have gotten out and met people and had some friends in this country ” Byars says.

Throughout their stay in Wilmington some of the prisoners actually enjoyed life in the camps. They spent their free time watching American movies listening to radio broadcasts and gardening. Several ran a canteen. Many of the local farms and mills that hired them would have closed without the labor of the prisoners. They worked in Castle Hayne and other surrounding areas. One location was the Leeuwenburg Farms on what is now north Market Street. The owner Otto Leeuwenburg hired about 50 men and remembered them fondly. By law (Geneva Convention 1929) POWs could only work on farms or other locations if they were paid a regular wage.

“I remember their faces as if it were yesterday. They were Germans but not Nazis ” Leeuwenburg said. The prisoners were paid minimum wage for their jobs and they were treated well by guards. In fact most of the POWs behaved in such artless fashions that near the end of the war they were allowed to go to their jobs alone without supervision from the guards. Friendships grew between the employers and the prisoners.

Some POWs maintained contact with the local dairy farmers after returning home Jones says.

An example of such good relations took place at Echo Farms a dairy farm that is today the location of the Echo Farms housing development. After the war J.D. McCarley Jr. the farm’s owner stayed in touch with many of his German employees.

In one letter McCarley wrote to former POW Bernhard Thiel “All of you boys that worked for me during the war are in my thoughts quite often. Quite a few of you have written to me and I am always [glad] to hear that you have gotten safely back to your native land.”

Prisoner Max Speth wrote to McCarley in 1948 “I never had as good a time as I had on your farm.”

As strong relationships grew between farm owners and the Germans the citizens of the city also developed bonds with some of the prisoners. Though the prisoners were not allowed to move freely through the city during their jobs they were able to interact with a few residents. For example some children would visit Leeuwenburg Farms and see the prisoners working there. At first they would refuse offers of candy bars from the POWs believing the treats were poisoned. However as time passed the prisoners’ civility and kindness eventually won over the citizens of Wilmington and the general feelings of contempt and fear all but disappeared.

In May 1945 the war against Germany ended and by the spring of 1946 all of the prisoners were home or on their way back overseas. The Wilmington Morning Star summed up their absence: “The prisoners’ departure strikes three sad blows — one to the farmers one to the community and one to the prisoners themselves.”

Although there was a rocky beginning to the prisoners’ time in Wilmington they became widely recognized as an indispensable help in the food production industry and are ultimately remembered as sympathetic men who left an indelible mark on the city.