Ocean Avenue vs. The Ocean

BY Gretchen Nash

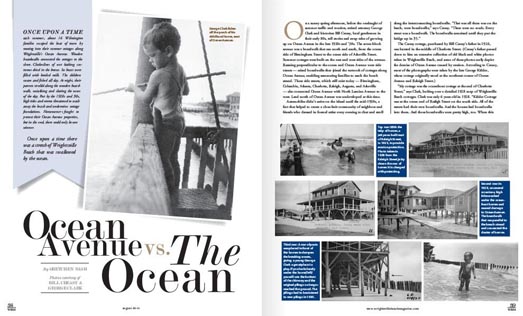

Once upon a time each summer about 16 Wilmington families escaped the heat of town by moving into their summer cottages along Wrightsville’s Ocean Avenue. Wooden boardwalks connected the cottages to the shore. Clotheslines of wet bathing costumes dried in the breeze. Ice boxes were filled with bottled milk. The children swam and fished all day. At night their parents strolled along the wooden boardwalk socializing and sharing the news of the day. But by the 1920s and ’30s high tides and storms threatened to wash away the beach and undermine cottage foundations. Homeowners fought to protect their Ocean Avenue properties but in the end there could only be one winner.

Once upon a time there was a stretch of Wrightsville Beach that was swallowed by the ocean.

On a sunny spring afternoon before the onslaught of summer traffic and tourists retired attorney George Clark and historian Bill Creasy local gentlemen in their early 80s tell stories and swap tales of growing up on Ocean Avenue in the late 1920s and ’30s. The seven-block avenue was a boardwalk that ran north and south from the ocean side of Birmingham Street to the ocean side of Asheville Street. Summer cottages were built on the east and west sides of the avenue. Running perpendicular to the ocean and Ocean Avenue were side streets — raised boardwalks that joined the network of cottages along Ocean Avenue enabling summering families to reach the beach strand. These side streets which still exist today — Birmingham Columbia Atlanta Charlotte Raleigh Augusta and Asheville — also connected Ocean Avenue with North Lumina Avenue to the west. Land north of Ocean Avenue was undeveloped at this time.

Automobiles didn’t arrive on the island until the mid-1930s a fact that helped to create a close-knit community of neighbors and friends who dressed in formal attire every evening to chat and stroll along the interconnecting boardwalks. “That was all there was on the beach were boardwalks ” says Creasy. “There were no roads. Every street was a boardwalk. The boardwalks remained until they put the bridge up in ’35.”

The Creasy cottage purchased by Bill Creasy’s father in 1926 was located in the middle of Charlotte Street. (Creasy’s father passed down to him an extensive collection of old black and white photos taken in Wrightsville Beach and some of these photos eerily depict the demise of Ocean Avenue caused by erosion. According to Creasy most of the photographs were taken by the late George Kidder whose cottage originally stood at the northeast corner of Ocean Avenue and Raleigh Street.)

“My cottage was the oceanfront cottage at the end of Charlotte Street ” says Clark looking over a detailed 1928 map of Wrightsville Beach cottages. Clark was only 6 years old in 1928. “Kidder Cottage was at the ocean end of Raleigh Street on the south side. All of the streets had their own boardwalks. And the houses had boardwalks into them. And those boardwalks were pretty high too. When this was first built my recollection is that it did not have side rails at all. It later did. The erosion was a terrible problem even back then.”

At the time little was known about the physics of coastal erosion but Ocean Avenue residents hoped for the best by placing breakwaters and rows of wooden posts in front of houses to slow down the wave action. These erosion controls say both men were left up to individual homeowners. The Town of Wrightsville Beach built several jetties to trap the shifting sand and according to Creasy and Clark they were effective.

“Well they understood that jetties worked ” says Clark.

“That’s exactly what I was going to say ” adds Creasy. “We had about seven jetties all up and down this beach from the south end to the north end and at a certain time of the year and (around the jetties) the sand on one side would be up to the top and the other side would be way down. And then the next season it would shift. The sand was just moving back and forth back and forth. Wouldn’t you say that George?”

“Yes I would. And then eventually the jetties were made of creosoted piles and creosoted wood and they disintegrated over time and became ineffective. But the thing that actually saved the beach was the dune and berm project ” says Clark of the project to dredge Bird Island (across from the Yacht Club) in the 1960s. “That saved Wrightsville Beach. And I think it will be there from now on.”

But the sea continually nipped at the heels of Ocean Avenue’s oceanfront homes. And then in 1929 Mother Nature shook the family cottages to the bone undermining pilings and wiping out breakwaters and jetties. In the captions that accompany the photos Creasy writes that the “high tides of September 21-22 1929” brought the Ocean Avenue residents face to face with the reality of the power of the ocean. In today’s high-tech world these high tides would have likely been associated with a hurricane and Jim Cantore from the Weather Channel would have been on the beach.

Of course at this time weather predictions didn’t exist and Ocean Avenue families were unprepared for the devastating tidal surges and storms that eventually wrecked their homes. By 1933 houses were left tilting on their frames water rushed underneath pilings which had already been spliced for additional support boardwalks buckled and porches collapsed in the swelling tide.

Some houses like Clark’s first family cottage washed away; others were moved westward or were rebuilt in other locations. “You can see a picture of me fishing off of our porch at that cottage before the fire this was the early cottage with a cane pole fishing straight down ” says Clark. “That’s how problematic the water was.”

If erosion didn’t get the remaining cottages the fire of 1934 did. Ironically it was a curse for some and a blessing for others. Some people Clark explains believe that the wooden boardwalks acted like slow fuses that spread the fire from one block to the next. In the 1930s beach owners didn’t have flood insurance but they did have fire insurance. “My family was jubilant when the fire burned because they had fire insurance and could build another cottage ” says Clark “probably 150 yards west of where the other cottage had been.”

“Well we weren’t that jubilant when our cottage burned on Charlotte Street ” says Creasy of the house located on the west side of Ocean Avenue. “We were halfway up the block you know. And that’s when Daddy sold that lot after the fire and bought that lot that we have now.

“I remember the fire because my dad and I stood on Harbor Island. They wouldn’t let us on the beach. And we watched the beach burn. I was only 6 years old then. But I have a memory of that fire ” he said.

More than 100 homes on the northern extension of Wrightsville Beach were destroyed in the January 1934 fire. The landscape was dotted by charred brick foundations and graveyards of chimneys. Creasy writes “September 1934 and the ocean is nearly victorious — only the Kidder cottage remains east of the Ocean Avenue boardwalk. The rest burned in the January 1934 fire were relocated or were claimed by the ocean.”

Except for good memories and a handful of photos Ocean Avenue is merely a phantom of Wrightsville Beach. But there is one gentle reminder left of the battle between Ocean Avenue and the ocean. At low tide if you are patient you can just make out the tops of pilings that once formed the jetty off of Birmingham Street.