Migratory Journeys

BY Colleen Thompson

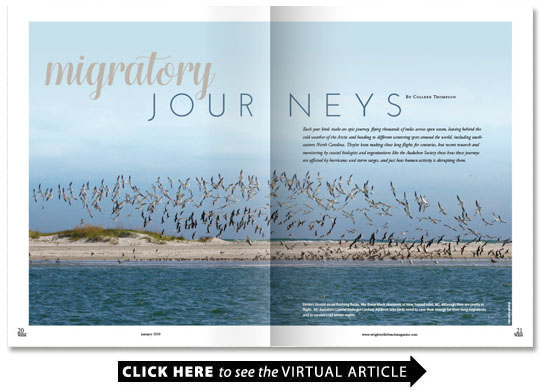

Each year birds make an epic journey flying thousands of miles across open ocean leaving behind the cold weather of the Arctic and heading to different wintering spots around the world including southeastern North Carolina. They’ve been making these long flights for centuries but recent research and monitoring by coastal biologists and organizations like the Audubon Society show how these journeys are affected by hurricanes and storm surges and just how human activity is disrupting them.

Growing up in Wrightsville Beach Walker Golder has been surrounded by birds and wildlife all of his life. Early on he developed a fascination with the seasonal comings and goings of local wildlife — the summertime when terns and skimmers nested on remote beaches; the cooler months that brought ducks to the marshes and shorebirds to the beaches. Bluefish Spanish mackerel and speckled trout each had their seasons of abundance and each captured his attention. This intrigue led to degrees in biology (BSc) and marine biology (MSc) from UNCW. Fresh out of graduate school he landed a job with the National Audubon Society as the first manager of the newly created North Carolina Coastal Islands Sanctuary program. Later on he launched the North Carolina Important Bird Areas Program and became deputy state director when the state office was formed. Today he serves as the director of the National Audubon Society’s Atlantic Flyway Coast Strategy where he works with organizations worldwide to advance conservation of coastal areas that are important to sustaining populations of seabirds shorebirds and marsh birds.

“I get excited when the terns and skimmers come back to nest when shorebirds from the Arctic arrive on our beaches hearing the whistling of ducks’ wings in the winter and the moment a redfish takes a fly crafted by my own hands ” Golder says. “Through it all I have stayed connected to my roots and the rhythms of the coast. Whether pursuing fishing surfing sailing boating or walking on the beach any time spent in the proximity of water refreshes me.”

Migration in the region varies depending on the species. For some shorebirds it begins as early as July. Southbound migration usually called fall migration ends in December for most species that choose to overwinter in the area.

Northbound migration called spring migration begins for some species in February and continues until June.

The National Audubon Society has designed a conservation blueprint called Important Bird Areas (IBAs) — areas important to birds at some time during their annual cycle including breeding migration and wintering periods. To date 30 North Carolina IBAs have been approved by BirdLife International as globally significant including on Masonboro Island and Lea-Hutaff Island (shorebirds waterfowl marsh birds marsh-dependent songbirds) and on the Lower Cape Fear River (shorebirds waterfowl marsh birds songbirds wading birds marsh-dependent songbirds).

“Our region of the state has a great diversity of habitats and therefore of birds. We have lots of migratory seabirds shorebirds songbirds waterfowl marsh birds raptors and others in this area — making it a wonderful place to live ” Golder says.

For the past eight years Lindsay Addison has been a coastal biologist with Audubon North Carolina. She manages monitors and helps protect 15-20 nesting sites annually that support over one-third of North Carolina’s nesting coastal waterbirds including Lea-Hutaff Island the south end of Wrightsville Beach and islands on the Cape Fear River. The breeding work includes monitoring species like American oystercatchers pelicans terns and wading birds. Many species like sanderling dunlin short-billed dowitcher ruddy turnstone and marbled godwit only appear during the non-breeding season.

Although most people associate the beach with gulls there are many more bird species that are found in southeastern North Carolina. Most species of shorebirds — sandpipers plovers and their relatives — nest in the far north as far as the Arctic and winter in the south anywhere from the mid-Atlantic coast of the U.S. to South America ” Addison says. “They depend on coastal habitats especially inlets for places to forage and rest on their long migrations. Without these habitats they would not be able to survive to reach their breeding and winter grounds.”

These crucial habitats have become increasingly threatened as hurricanes like Florence have barreled through the region displacing birds and disrupting food supplies. Birds and hurricanes have coexisted for millenia in an annual life-and-death struggle and survival has never come easy for birds be they migratory land birds shorebirds or birds that spend most of their time over open water.

“Pelagic seabirds that usually occur far out at sea ended up on inland lakes as far away as Raleigh and Greensboro ” Golder says. “After Florence there was a Trindade petrel near Raleigh; a brown pelican that should have been on the coast was seen near Burlington. After Hurricane Matthew there was a flamingo (likely from Cuba or the Bahamas) on the coast of S.C. ” Golder says. “During Florence many black skimmers that are usually around area inlets moved inland and were reported in odd places like on area roads highways and overpasses and unfortunately some were hit by cars. I observed a skimmer flying down the center lane of Market Street and counted 14 dead skimmers in the vicinity of the 17-140 overpass in Porters Neck.”

While a hurricane is still over the ocean birds will often seek shelter in the eye and keep flying inside of it until the storm passes over the coast where they will take refuge on land. It is also why birders flock to areasstruck by hurricanes — the storms provide an opportunity to spot species in places where they are not supposed to be.

“Over the ocean hurricanes can affect migrating birds by directly impacting them when the birds get caught in them. These birds can end up being carried off-course by hundreds of miles and show up in unusual places as a result ” Addison says. “Other birds at sea might be forced to fly around them as in the case of a whimbrel that was being tracked with satellites and detoured hundreds of miles.”

Birds however are remarkably resilient and they will find ways to shield themselves from the wind and rain seeking shelter on the lee side of trees or buildings in shrubbery or anywhere they can.

“They don’t have the Weather Channel and they really don’t know how strong or large a storm might be. But they can detect changes in barometric pressure and studies have shown that they increase food intake in response to declining pressure. They’re also good at finding small patches of habitat and food but there is a lot that we don’t know about birds’ ability to cope with storms ” Golder says.

With that said they have to have the habitat to sustain themselves and recover from major events like hurricanes. Sometimes however it is less about coping with storms and more about finding the specific habitat they need. Least terns black skimmers and some shorebirds for example need open bare or sparsely vegetated sandy or sand-shell habitat for nesting. This habitat is created by overwash — when storm-induced waves exceed the height of the dune sand is transported over the top of the dune and deposited inland and this process known as overwash causes a significant change in the landscape of the island. The birds are excellent at finding these habitats but the problem is finding undeveloped barrier islands where the ends of barrier islands near inlets can overwash. Jetties terminal groins and other hard structures at inlets or other shorelines prevent the natural dynamics of barrier islands and eliminate habitat that beach-nesting birds depend on.

“We need to protect and restore the habitats birds depend on so that birds can cope with periodic disruptions in habitat or food availability in the wake of hurricanes ” Golder says. “We need to make sure that habitats are resilient to storms and climate change.”

Resilient healthy coastal ecosystems not only benefit birds; they serve as the first line of protection for our coastal communities facing stronger more frequent storms and sea level rise. It’s why Audubon is advancing strategies to help the Atlantic shoreline adapt to the impacts of climate change. Marshes barrier islands oyster beds and tidal flats — “green infrastructure” — harness nature’s own defenses and are often more effective in containing storm surge and protecting coastal communities than “gray infrastructures” like jetties groins and seawalls (which can do more harm than good). These climate-smart solutions not only buffer the impacts of storms reduce flooding and minimize wetland loss but they also protect biodiversity and support healthy populations of birds and fish.