Keeping Time

BY Stephanie Miller

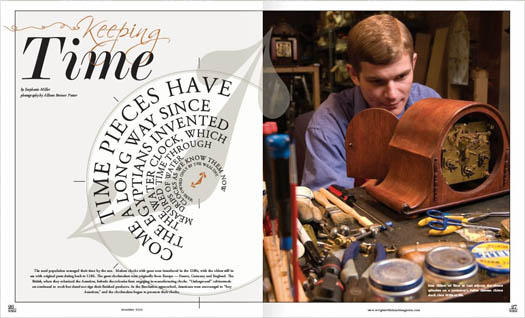

Time pieces have come a long way since the Egyptians invented the water clock which measured time through drips of water. Clocks as we know them now were owned only by the wealthy. The rural population managed their time by the sun. Modern clocks with gears were introduced in the 1200s with the oldest still in use with original parts dating back to 1286. The great clockmakers were originally from Europe France Germany and England. The British when they colonized the Americas forbade the colonies from engaging in manufacturing clocks. “Underground” cabinetmakers continued to work but dared not sign their finished products. As the Revolution approached Americans were encouraged to “buy American ” and the clockmakers began to promote their clocks. The grandfather clock which is a weight-driven clock was the most popular time piece in this country for the 50 years before the Revolution and it enjoyed a resurgence that lasted until the 1830s when fashionable homes began to display shelf clocks. Spring-driven shelf clocks became popular and after the Industrial Revolution comprised the majority of the clocks on the market. Early clock manufacturing in this country was done with a kind of mass-production approach that influenced what is known now as the “American System” or the “American Process” of mass production. As the American economy became more industrialized and the keeping of time became universally more important the advent of the clock as a utilitarian object rather than a fashion statement became de rigueur and the grandfather clock gave way to smaller less architectural pieces. “The insides of the clocks have remained pretty much the same ” says Wilmingtons Al May of Al May Clock Repair. The mechanism that drives antique clocks (clocks 100 years or older) is called “the movement” and is spring-driven or weight-driven. The grandfather clock is driven by multiple weights. One powers the clock. Another powers a chime that may sound every 15 minutes the Westminster chime from the University Church Tower of St. Marys in Cambridge England for instance. A third weight may control the strike at the top of the hour which strikes the time according to its number. Yet another weight may move a dial that tracks the phase of the moon a critical time teller for an agrarian economy. More than any other feature the sound of the chimes or the bells drives people to bring their clocks in for repair at Wrigleys Clocks and Fidlers Gallery at the Cotton Exchange in Historic Downtown Wilmington. People arrive daily to repair an heirloom clock just uncovered in the back of a closet. “Families want it to run for sentimental reasons and for the love of the sound ” says owner Garry Hayward. “Sound is one of the most important selling features of a clock too ” say Alex Clifton owner of Castle Streets Time at Last a retail store and repair shop dedicated to clocks of all kinds. Cliftons store is all about history. Theres an oversized French chime clock with a porcelain dial and beveled glass that sounds like something out of another era because it is out of another era. There are ornate shelf clocks with sculpted figurines double dial calendar clocks that record the date day of the week and the month and old cuckoo clocks chiming every which way throughout the day. Clifton is tucked away in the back of the store seated at his watchmakers bench which is as old as many of the clocks in his shop dating back to the early 1900s. The workbench itself is a tribute to the craftsmanship of its owner twelve-plus drawers hide hundreds of small springs and bolts; a waist-high shelf with raised edges to keep small pieces from rolling onto the floor (never to be found) pulls out and sits on Cliftons lap. “I spent many hours on my knees ” says Clifton remembering when he didnt have that special shelf. Clifton is a student of the history of timepieces and clock repair and is often amazed at the clocks that wind up in his shop. “Once in a while I say Wow I didnt know thered be one of those in this state let alone in my shop.” He and his collectors delight in pieces that are 200 years old and are still functioning. “Its a great conversation piece the path that clock has taken. Clocks built during the Civil War just imagining where that clock has been and what its seen.” The sheer beauty of the piece is another strong attraction for Clifton. “You just dont see that kind of craftsmanship anymore ” he says. “We live in a disposable society. If something breaks down we throw it away and get a new one. That we can always make these old clocks work is very cool to a lot of people.” And then there is Jim Overton DDS. Overton a Wilmington dentist didnt peruse the Crate and Barrel registry when it came time to give a wedding gift to each of his three children. Instead he went into his workshop and began the arduous process of building a grandfather clock from the ground up using wood from his yard a black walnut tree downed by a hurricane. How and where and when does one begin to even think about building a grandfather clock from scratch? For Overton the journey began when he decided to build a clock for his wife by copying the plans for a grandfather clock that won first place in the 1998 American Woodworker magazine contest a contest that he had entered. The first-place winner an OB/GYN from Concord North Carolina designed a Newport-style grandfather clock one of the most popular styles of grandfather clocks harkening back to the mid-1700s when Newport Rhode Island was one of the centers of cabinetmaking that was modeled after a grandfather clock in the Metropolitan Museum. Overton copied the Concord doctors plans but six months into the project hit an impasse. The OB/GYN realizing he had sent incomplete instructions apologized profusely and wondered aloud how the dentist had gotten as far as he had. “I didnt know I couldnt do what I had done ” says Overton laughing. It took another six months to complete the project a long time in clock making. So long in fact that the Port Citys salty air had time to corrode the mechanism. Overton had to ask the clockmaker to take the mechanism apart clean it and put it back together again. (Todd Reynolds formerly of Clockwise at Plaza East is the clockmaker.) After a year Overton presented the finished piece as a gift for his wife. The Tall Case clock modeled after the Newport clock housed a mechanism that came from a company known for crafting timepieces like those made 200 years ago. Overton added a personal touch to the heirloom contracting a South Carolina artist to paint a drawing of his (Overtons) old home built in 1730 on the clock dial. When his three children saw the clock they fell in love with it. After their father told them the story of the wedding gift all three begged him to do the same for them. Having just completed a years worth of labor on the piece for his wife Overton thought for a moment and said “Well it better be a long engagement.” Overtons younger daughter was the first to walk down the aisle. She got engaged on the front porch of the Overton home and her engagement ring was attached to a little kitten. So the dentist requested that the same South Carolina artist who painted his first clock dial now paint an orange kitten on the dial of his daughters grandfather clock. “That kitten wouldnt mean anything to anyone else but it blew them away ” says Overton. Overtons son was next. Jim stole a painting off his sons fiances wall. It was a painting by Mary Ellen Golden of the Carolina Yacht Club as seen from the sound with a sailboat race in progress. Overton took the painting home photographed it and sent the image to the artist but not before he changed one of the sail numbers to reflect the date of the wedding. For the last wedding scheduled for October 2011 Jim is generating a grandfather clock with a Wrightsville Beach lifeguard stand on its moon dial because thats where his daughters fianc popped the question on a balmy Saturday evening in August. “I dont know how the artist will do this ” says Overton “but somewhere in that painting will be that lifeguard stand.” Craftsmen and clock lovers like Overton May Hayward and Clifton are in it for the long haul like their clocks. “Most of the horologists I know are getting on in years ” says Clifton. “You think its tough to find somebody to work on these clocks now? In 10 20 years its going to be very very difficult.”