Homemade International Aid

BY Charlotte Smith

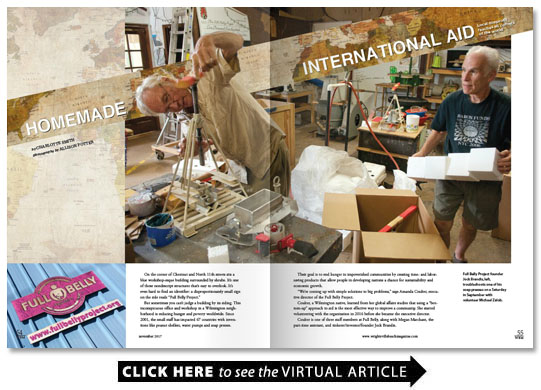

On the corner of Chestnut and North 11th streets sits a blue workshop-esque building surrounded by shrubs. It’s one of those nondescript structures that’s easy to overlook. It’s even hard to find an identifier: a disproportionately small sign on the side reads “Full Belly Project.”

But sometimes you can’t judge a building by its siding. This inconspicuous office and workshop in a Wilmington neighborhood is reducing hunger and poverty worldwide. Since 2001 the small staff has impacted 67 countries with inventions like peanut shellers water pumps and soap presses.

Their goal is to end hunger in impoverished communities by creating time- and labor-saving products that allow people in developing nations a chance for sustainability and economic growth.

“We’re coming up with simple solutions to big problems ” says Amanda Coulter executive director of the Full Belly Project.

Coulter a Wilmington native learned from her global affairs studies that using a “bottom-up” approach to aid is the most effective way to improve a community. She started volunteering with the organization in 2016 before she became the executive director.

Coulter is one of three staff members at Full Belly along with Megan Marchant the part-time assistant and tinkerer/inventor/founder Jock Brandis.

“If you can make a small improvement in small farm income you make a huge improvement in the entire national economy ” Brandis says. “We try to teach farmers how to get the most product from a day’s labor in a plot of land. Which is in a word efficiency. Sometimes all you need is a gizmo that makes shelling peanuts 50 times faster. Or a gizmo that means your whole crop gets to market without it being spoiled or eaten by insects. It’s all about efficiency.”

At first glance 70-year-old Brandis might be mistaken for a mechanic rather than an inventor. There’s no lab coat no electrified hair no maniacal laugh; just a raggedy work shirt jeans and grease-stained hands — and one heck of a mind for problem solving. He can create something from almost nothing: desks and boards out of plastic bags; an oven out of insulation metal and heating elements; irrigation pumps out of discarded PVC pipe and more.

“He’s lived his whole life perfecting the art of creating abundance within scarcity ” says Coulter who calls Brandis the MacGyver of the organization. “He can always just figure out the best way to get the most done with the smallest amount of money or the smallest amount of resources.”

Brandis learned how to solve problems with scarce access to resources while being raised on a farm in rural Canada.

“I got the mind for very simple solutions because you couldn’t just go to Lowes you had to look around the farm ” he says. “Good way to grow up. I highly recommend it.”

The farm boy found his way into the movie business eventually moving to Wilmington to work with Dino De Laurentiis. But he began to grow disillusioned with the glitz and glamor and the egos. He decided to switch gears and work in nonprofit.

“Sometimes too late in life you take your father’s advice ” he says. “I was raised on a farm and my father started a farm cooperative and was always involved with farmers and trying to help farmers work cooperatively. And when he heard that I was going to go to Hollywood to hang around in hot tubs with starlets he tried to persuade me that maybe it would be more fun to do other stuff. There was a time that I thought there’s nothing more fun than hanging around in hot tubs with starlets. I was wrong about that. � And my mother raised me to be of service to other people. And the hot tub thing didn’t really work that way.”

Thus the Full Belly Project was officially born in 2003. And it all started with peanuts.

During a trip to Mali Brandis noticed a woman’s bleeding and calloused hands. They were caused he was told by shelling peanuts for the market an arduous and time-consuming task. The peanut or groundnut as it is called locally is a critical subsistence crop for families in West Africa providing a source of both income and nutrition. Brandis invented the universal nut sheller (UNS) a simple machine with two concrete cones and a hand crank to decrease time and discomfort while increasing potential for income and access to nutritious food.

The user pours peanuts into the inner cone. They migrate to an opening between the two cones. When the user spins the metal handle the shells are broken and the nut falls into the basket below. The device can shell about 100 pounds of peanuts in an hour Coulter says. The task would typically take a group of women three days to complete. Brandis’ UNS is now in use in 40 countries.

Earlier this year Full Belly sent 105 of the peanut shellers to a farmers’ co-op in Zambia. They also ship plastic molds and instructions to Zambia and other countries so farmers can produce and distribute their own shellers made with locally sourced material.

Rooted in its humble beginnings with the peanut sheller Full Belly has expanded to well anything from farm irrigation to personal hygiene creating products and devices at the small workshop in Wilmington and shipping them overseas.

Where possible the products are made from recycled materials found locally. For instance water pumps that allow for foot-operated irrigation are made with leftover PVC pipe from construction sites and rubber from Hughes Brothers Inc. a nearby tire store.

Recently a dairy in Kenya approached Full Belly looking for a solution to keep milk from spoiling before it could be taken to market. Brandis is working on a product to keep milk fresh by using a metal container a water cooler and discarded cold packs from hospitals.

“Jock is constantly coming up with ideas because there’s still so many problems that we can potentially solve with what we call appropriate technology tools that will work in a developing context without electricity or running water and all that kind of stuff ” Coulter says.

But Brandis is only one man and he needs help. That’s why the Full Belly Project relies on volunteers old and young to pick up the slack.

“We call ourselves Wilmington Polytech ” he says.

His volunteers ranging from high school students to retirees do everything from welding to woodworking and beyond. The workshop is littered with tools and materials. A black cat meanders between peanut shellers and worktables containing inventions in various stages of completion including Brandis’ latest project boards that could potentially be used as construction materials in developing nations. They’re made from 500 plastic bags.

When the younger volunteers are well behaved they get to tinker with a World War II English motorcycle.

“On Saturday the whole thing just becomes kind of a social event ” Brandis says. “People make friends within the volunteer group.”

Working with the local community is the cornerstone of the Full Belly Project. The organization is planning a program with John T. Hoggard High School’s Beta Club in which the members would be involved in all the phases of an international development project from fundraising to building to packing and shipping.

“We are helping people in developing countries but we are creating global citizens right here in Wilmington ” Coulter says.

In the meantime there’s work to be done. Full Belly is now distributing soap presses that sanitize and recycle otherwise wasted soap. Every year a typical 400-room hotel throws away up to 3.5 tons of bar soap while children die every day in rural developing areas from diseases that could have been prevented by hand washing. A program called Soap for Hope utilizes the soap presses to recycle soap waste create reliable income for the soap maker and distribute direly needed soap in locations with reduced access to hygiene and sanitation.

The user places the leftover soap in the device which is made from a threaded rod and aluminum plates. When the user spins the wooden handle the recycled soap is cold-pressed into a new bar. Full Belly gives the presses to women who are paid per bar. They add ingredients depending on their geographic region: mosquito repellent in Africa to cut down on the risk of malaria; coffee in South America to reduce wrinkles. Local nonprofits then distribute the soap.

Brandis calls the soap press a “win-win-win all around” for the women and local economies that benefit from the job the hotels that receive positive publicity and for communities that didn’t previously have access to soap and hygiene education.

The products developed by Full Belly have applications that can be used here in the United States. In North Carolina’s Scotland County Brandis is helping farmers set up solar irrigation systems. In Wilmington rocker water pumps are distributed to gardeners. Brandis gives long-distance instruction on how to use solar water pumping and sends links containing product development instructions to farmers.

“We are farmers’ friends not just foreign farmers’ friends ” he says.

But it’s overseas where the nonprofit is making its dramatic difference.

“We take a country or a population that is stable and help them reach the next level ” Coulter says. “We can help them develop to where they are food secure they don’t have to worry about where their next meal is coming from and they have enough money to send their kids to school. Just increasing a person’s income in a developing country by $10 makes a huge difference.”