History and Heritage: Gullah Geechee in North Carolina

BY Cindy Ramsey

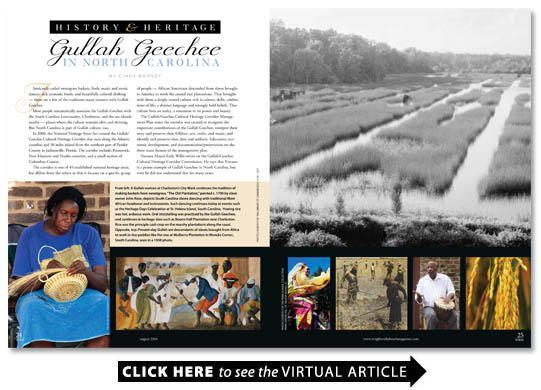

Intricately coiled sweetgrass baskets lively music and exotic dances rich aromatic foods and beautifully colored clothing — these are a few of the traditions many connect with Gullah Geechee.

Most people automatically associate the Gullah Geechee with the South Carolina Lowcountry Charleston and the sea islands nearby — places where the culture remains alive and thriving. But North Carolina is part of Gullah culture too.

In 2006 the National Heritage Areas Act created the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor that runs along the Atlantic coastline and 30 miles inland from the northern part of Pender County to Jacksonville Florida. The corridor includes Brunswick New Hanover and Pender counties and a small section of Columbus County.

The corridor is one of 49 established national heritage areas but differs from the others in that it focuses on a specific group of people — African Americans descended from slaves brought to America to work the coastal rice plantations. They brought with them a deeply rooted culture rich in talents skills celebrations of life a distinct language and strongly held beliefs. That culture lives on today a testament to its power and beauty.

The Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Management Plan states the corridor was created to recognize the important contributions of the Gullah Geechee; interpret their story and preserve their folklore arts crafts and music; and identify and preserve sites data and artifacts. Education economic development and documentation/preservation are the three main focuses of the management plan.

Navassa Mayor Eulis Willis serves on the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission. He says that Navassa is a prime example of Gullah Geechee in North Carolina but even he did not understand that for many years.

“Approximately 75 percent of North Carolina Gullah Geechee don’t realize they are Gullah Geechee ” Willis explains.

Willis remembers being mesmerized by the 1977 TV mini-series “Roots” based on a book by Alex Haley. It inspired him to research his own roots. To improve his knowledge he signed up for a local history class at Cape Fear Community College. The result of his studies energy and imagination was a book called “Navassa: The Town and Its People.”

Willis learned that Navassa is a prime example of Gullah Geechee in North Carolina. In fact during the development of the management plan his book’s chapter on rice plantations — written 15 years earlier without any idea of its significance — was used as a reference.

Willis says a key point to remember is the difference between history and heritage.

People have no choice as to their heritage — those from whom they are descended. But history is made by choices — the culture chosen or left behind.

People in North Carolina had more choices than their counterparts in South Carolina. The cultures of Gullah Geechee and other North Carolinians became blended and many of the mother-country traditions were less practiced.

This blending of cultures could be directly attributed to the land — a sense of self directly attributed to a place.

In 1865 Special Order No. 15 proposed by General William Tecumseh Sherman set aside the sea islands from Charleston to the St. John’s River at Jacksonville Florida for the settlement of emancipated slaves. A large influx of freed people settled in South Carolina and Georgia. Even though the order was rescinded one year later many families remained and became self-sufficient. There the Gullah Geechee culture survived through proximity to each other and isolation from outside influences.

That was not the experience of North Carolina Gullah Geechee and the culture suffered. But Willis is quick to assert “We’re still as much Gullah Geechee as the next guy.”

Using words from the Gullah Geechee language Willis describes two types of Gullah Geechee in Navassa. The binyahs are people who have always lived there. The comyahs are people who moved to the area looking for work. The comyahs know that they are Gullah Geechee while the binyahs don’t always recognize that as fact.

Madafo Lloyd Wilson a Wilmington native who passes on African history culture and tradition through storytelling affirms that the Gullah Geechee people lived this far north but suggests most of their descendants are binyahs.

“Most of the Africans who were living in Wilmington were Gullah ” he says. “My grandmother and my mother used to speak the dialect to each other when I was a kid. But our children are growing up with a very dim view of who they are and who their ancestors were. We don’t know our culture or who we are or where we came from.”

Caroline Lewis executive director of Poplar Grove Plantation in Pender County would love to see local scholars and educators take the Gullah Geechee history and culture more seriously.

“It’s sometimes viewed as mythology and too easily dismissed ” she says.

Lewis points to the strength skills intellect and fortitude required for all the detailed work that plantation slaves accomplished. She references the math and other skills needed for blacksmithing and planting cooking and creating clothing.

“The masters did not have these skills ” Lewis says. “The slaves did. But it was easier to think of those skills as being intuitive rather that intellectual.”

Retired educator Beverly Smalls says the focus of Gullah traditions in the Wilmington area is scholarship — to study teach and preserve the culture.

The Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Management Plan states at least one Coastal Heritage Center will be established in each state in the corridor. They will provide “a community anchor that focuses on a living group of people that connects the past and the present through interaction and outreach across generations; a physical space that embodies the vision and mission of the corridor.”

Lewis believes that heritage arts is the best way to anchor the celebration of Gullah Geechee culture.

“Heritage arts are those skills that have a utilitarian purpose and are passed down from generation to generation ” Lewis says. “Skills like blacksmithing carpentry basket making weaving.”

Many are an expression of individuality and artistic expression — the designs in the baskets the patterns and colors of woven cloth and the clothes and quilts created from that cloth. While the baskets most identified with Gullah Geechee in the Charleston area are created from sweetgrass the same skills and techniques are used in North Carolina to create baskets from the bountiful source of longleaf pine needles.

Language music and dance are also customs celebrated by Gullah Geechee. What many people may not realize is that some of the foods Southerners love came from the Gullah Geechee culture: shrimp and grits okra and tomatoes barbecued pork and hoppin’ John just to name a few.

Smalls says she grew up eating rice at every meal. She thought everybody did but learned later that was part of her Gullah heritage as were seafood stews and vegetable stews. So were storytelling tales like Br’er Fox and Br’er Rabbit.

Smalls is only one of the Gullah descendants in the Wilmington area working on the scholarly piece of preservation and education. She says that planning and scholarship are the beginning of preserving the heritage for future generations.

While basket making and other arts may be the first things that come to mind when many people hear the term Gullah or Gullah Geechee Smalls wants everyone to understand that it is so much more than that.

“Gullah Geechee is a cultural heritage not based on three-dimensional objects ” Smalls says.

Much is to be learned taught and preserved for future generations. The establishment of the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor coupled with the management plan has established a place for the journey to begin.

Famous Gullah Descendants

Many famous and notable Americans trace their heritage to the Gullah people. Various websites dedicated to Gullah Geechee culture state that they include:

First Lady Michelle Obama

NBA Legend Michael Jordan

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas

NFL Hall-of-Fame Running Back Jim Brown

“American Idol” Season 12 winner Candice Glover

Filmmaker Julie Dash

Educator and civil rights activist Septima Poinsette Clark

Gullah Geechee Events

Many events within easy driving distance of Wilmington offer a chance to experience Gullah Geechee culture.

The Lands End Woodland River Festival St. Helena Island South Carolina. On St. Helena Island about 300 miles south from Wrightsville Beach via 1-95 the Labor Day Weekend festival (September 2-3) features an old-fashioned fish fry on the beach alongside African drummers dancers choirs vendors and storytellers.

34th Annual Heritage Days Celebration St. Helena Island. On November 11-12 visitors can gather to witness a festival of traditional dance music and more. This celebration will occur at the site of the former Penn School which was one of the country’s first schools for freed slaves.

Hilton Head Island Gullah Celebration. The annual celebratory showcase takes place every February. Tourists and locals alike experience Gullah cuisine learn about the local history and have the option to attend various programs designed to showcase the rich culture. This event also places a special emphasis on the visual arts.

The Gullah Festival Beaufort South Carolina. Held each Memorial Day the Gullah Festival features quilting and sweetgrass basket-making workshops arts and crafts tours of the Black Inventions Museum dance and food.

Poplar Grove Plantation Wilmington. The historic Poplar Grove Plantation features a permanent exhibit on local and regional Gullah Geechee history including agricultural practices such as the cultivation of peanuts sweet potatoes and melons and the culture of basket-making weaving and blacksmithing.

Gullah Culture and Local Artists

By Simon Gonzalez

Wilmington artist Minnie Evans is often associated with the Gullah Geechee. Her vibrant multicolored paintings resemble those of artists associated with the tradition and information about her life and work appears on the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor section of the National Park Service’s website.

However she differed from present-day artists such as Jonathan Green and Sonja Griffin Evans who identify as Gullah and use their work to help preserve the culture and history of their ancestors.

“Her paintings might suggest that she came out of the Gullah culture but I couldn’t say positive that she was Gullah ” says Madafo Lloyd Wilson a Wilmington native who studies and passes on African culture through storytelling.

Evans who died in 1987 at age 95 had an ancestor who was a slave. Her great grandmother’s grandmother a woman named Moni was sold into slavery in Charleston to serve a young bride as a part of her dowry. But while most Gullah trace their ancestry directly to West Africa Moni was brought to America from Trinidad.

Art historians say there are elements of Caribbean folk art forms in her work but Evans said that her paintings were the result of God-given visions. The vibrant colors were possibly inspired by the beauty of Airlie where she worked as a gatekeeper for 27 years and where she did most of her paintings.

Rocky Point native Ivey Hayes’ paintings also feature bold colors and abstract faceless figures reminiscent of Gullah art.

Hayes who died in 2012 at the age of 64 and was Evans’ cousin according to his brother Phillip Hayes was influenced by the African-American culture in North Carolina. His paintings depict blacks at work and play picking cotton and blueberries and digging potatoes making music and participating in sports.

But Hayes was not necessarily attempting to replicate history or revive a culture.

“Ivey did a lot of things relating to Africa ” Phillip Hayes says. “We talked about the Gullah and there are some things that probably influenced him. Ivey studied other artists all the time. That’s how he learned. But his real inspiration was things the Lord showed him. He just painted out of his head.”