Growing Up Barfield

BY Stephanie Miller

When New Hanover County Commissioner Jonathan Barfield was a boy in the 1960s he spent his weekends at his grandmother’s in Wrightsville Sound. Back then Lumina Station wasn’t a shopping and office center with trendy restaurants and boutiques. It was his great-uncle’s landfill. On Fridays and Saturdays Jonathan’s uncle would supplement his income by hauling trash onto the site and depositing the take into a big hole filled with water and bullfrogs.

When New Hanover County Commissioner Jonathan Barfield was a boy in the 1960s he spent his weekends at his grandmother’s in Wrightsville Sound. Back then Lumina Station wasn’t a shopping and office center with trendy restaurants and boutiques. It was his great-uncle’s landfill. On Fridays and Saturdays Jonathan’s uncle would supplement his income by hauling trash onto the site and depositing the take into a big hole filled with water and bullfrogs.

Life was slower too in the East Wilmington community where the young black man grew up. The dirt roads common in that part of the city slowed up the bicycles and automobiles. Muddy potholes opened up after the rains. Residents would have to wait for the sweeper to come by once a week to fill in the holes so driving could resume at a normal clip — until the next downpour.

Life might have been slower in those days but the laws of physics remained the same. Jonathan’s first-grade teacher had an “aerodynamic paddle.” Public school teachers were still allowed to paddle back in the early 1970s and his teacher who also taught Jonathan’s father made liberal use of the paddle which was riddled with holes. The flow of air through the holes allowed the paddle to move easily toward its target … often Jonathan. It turns out he had a gift for gab (even then) which didn’t sit right with the first-grade powers that be.

One of Jonathan’s more upbeat memories was his stint as a member of the Little Seahawks a group of boys who performed during half-time at the University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW) basketball games. One of the first members of this group Jonathan still cherishes a newspaper clipping of himself as a young boy handing a plaque to the now legendary John Calipari who played for UNCW from 1978-1980. Calipari head men’s basketball coach at the University of Kentucky is one of only four coaches to direct two different college teams to the number one seed in the NCAA Tournament. “Even in those days ” says Jonathan “people said he would never make a good basketball player but that he had a great coaching mind.”

Many evenings in the winter were reserved for basketball games but Sundays were always church days. The Barfield family church was Pilgrim Rest Baptist Church on Wrightsville Avenue (across the street from the Galleria). The church which recently held its 100th anniversary met on the second and fourth Sunday of the month. The church next door St. Matthews Methodist Church met on the first and third Sundays. The small African American community would go back and forth between the two churches. “It didn’t matter that one was Baptist and one was Methodist ” says Jonathan. “That’s just the way we did it.” Black churches also shared preachers who often traveled long distances to reach their congregations.

The congregation moved to a different church in the district every fifth Sunday for a Sunday school reunion. The children would attend Bible study all day and have a big picnic in the afternoon. Jonathan would travel with his grandfather on these Sunday excursions.

The congregation moved to a different church in the district every fifth Sunday for a Sunday school reunion. The children would attend Bible study all day and have a big picnic in the afternoon. Jonathan would travel with his grandfather on these Sunday excursions.

And on Saturday mornings he’d often travel with his grandmother in her big Buick. Jonathan says he cut his teeth on the yard-sale circuit gleaned from the newspaper classifieds and from callers to the Swap Shop program on the radio. At age 14 and a half when Jonathan got his learner’s permit he was his grandmother’s driver. “She found the neatest yard sales and I got a lot of practice driving her car.”

Once he got his license he bought himself an old clunker and headed out to Sports World (now Jellybeans) on Saturday nights. After the evening’s activities his crowd always headed out to the McDonald’s on Oleander Drive (now a Mexican restaurant). A big group would hang out at the tables outside the restaurant and enjoy the party atmosphere.

African American teenagers didn’t go downtown to socialize in Barfield’s day. The only time Jonathan headed that way was to receive shots at the Health Department.

The Seabreeze off Carolina Beach Road just before Snow’s Cut was another hot spot. The area was a thriving business district and attracted many black residents.

It was a true resort area for African Americans and the teenagers “owned” the Seabreeze night club on the waterway on weekend nights. “If you saw it in the day time you’d probably be scared to go on in ” Jonathan says. “But at night it really came alive.”

Even in his father’s day the Seabreeze was the place to go. Now it’s a very different place — buildings knocked down vacant land.

Being a black teenager in Wilmington was not easy. Jonathan didn’t encounter racism as an elementary school student at Blount which was integrated. But later on in junior high when he started taking the bus from his grandmother’s home along the Wrightsville Beach route the “n-word” surfaced many times. Racism died down for Jonathan when he entered into his high school years.

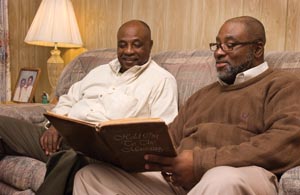

But it re-surfaced along his father’s county commission campaign trail in 1980. Barfield’s dad Jonathan “Joe” Barfield Sr. was the first African American elected to the position of county commissioner since post-war reconstruction in 1898.

Jonathan recalls campaigning for his father at Sunset Junior High School a school that no longer exists. “I can remember folks taking his literature and throwing it on the ground and stepping on it and kind of moving on.”

Joe recalls the campaign too. A group of citizens in the Spring View area across from Corning liked his platform and wanted to drum up support in their neighborhood but they couldn’t allow him to go in and campaign door to door until they prepared their neighbors.

“I remember saying to myself ‘Do I want to get elected? Do I want to deal with racial overtones?’” Joe says. In the end he wanted to get the job done so he went along with the procedures the group recommended and ended up carrying the neighborhood.

Joe’s time as county commissioner (1980-1992) saw the start of the county sewer system construction of the airport terminal restoration of the old courthouse and development of the senior center as well as funding for school construction.

Jonathan reminisces briefly about his experiences running as only the second black county commissioner both in his family and the county. “I had my oldest daughter work the polls for me at Ashley High School and she experienced some of the same things in this day and age where you have folks because of the color of someone’s skin still having that prejudice.”

But Jonathan sees a giant shift away from the prejudice of his youth. “People’s tolerance and acceptance of each other has definitely increased which is good ” he says.

All of these changes physical and societal Jonathan says are positive. He is a real estate broker so he appreciates the changes to the landscape of the city. As for his daughters he sees the cultural changes as having taken a step forward. “You need to learn how to interact with all kinds of people because once you go into the work force you’re going to be around all kinds of people.”

And being a people-person is what Jonathan Barfield Jr. is all about. Just sit down and talk to him for a few moments and you’ll discover that he is in part still that young boy who is thinking all the time and also a man who has witnessed incredible changes in his lifetime.