George Clark: A Lot to Say

Honoring living history

BY Pat Bradford

In October 2020, Wrightsville Beach Magazine published a Fish Tale, our first piece of fiction written by then-92-year-old George Clark Jr. Over the last 20 years, George may have been in our magazine more than any other Wrightsville Beach resident outside of our Social Seen pages. He just may hold the distinction of being our biggest fan, certainly one of our oldest.

Former state senator, a retired attorney, still incredible fisherman and an endearing person, George Clark Jr. has a lot to say. After all, he has 94 years of memories to share of life spent on Wrightsville Beach and in Wilmington.

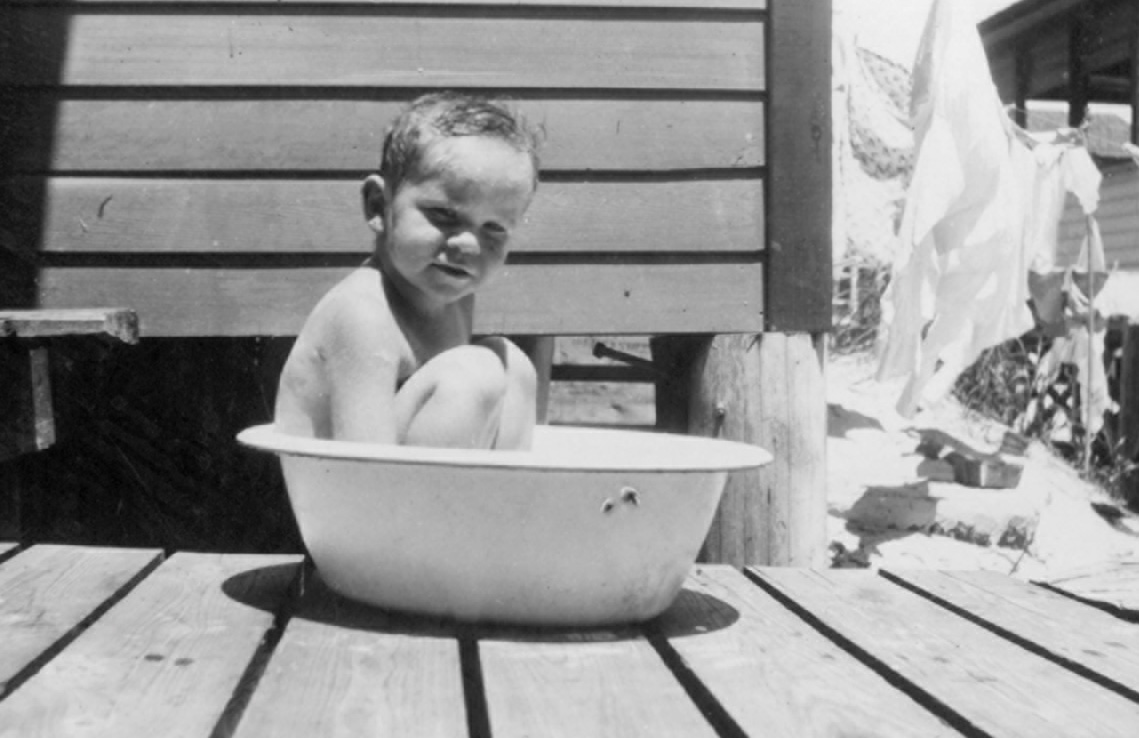

“All of my life,” he says. “We always had a home here. It wasn’t fancy but we had it.”

He’s been in his current home since 1968. He and his late wife Libby bought it when they moved back from Raleigh after he served as counsel to then-Gov. Jim Holshouser. George says his 50-plus-year-old wood frame cottage in Wrightsville Beach “is essentially a teardown” but to him it’s home. He has a multitude of memories of life lived there.

A New Hanover High School alumnus, George also looks back on a life filled with accomplishments. Besides his law practice and time in the legislature, he was legislative counsel to a North Carolina governor, and New Hanover County Board of Education member.

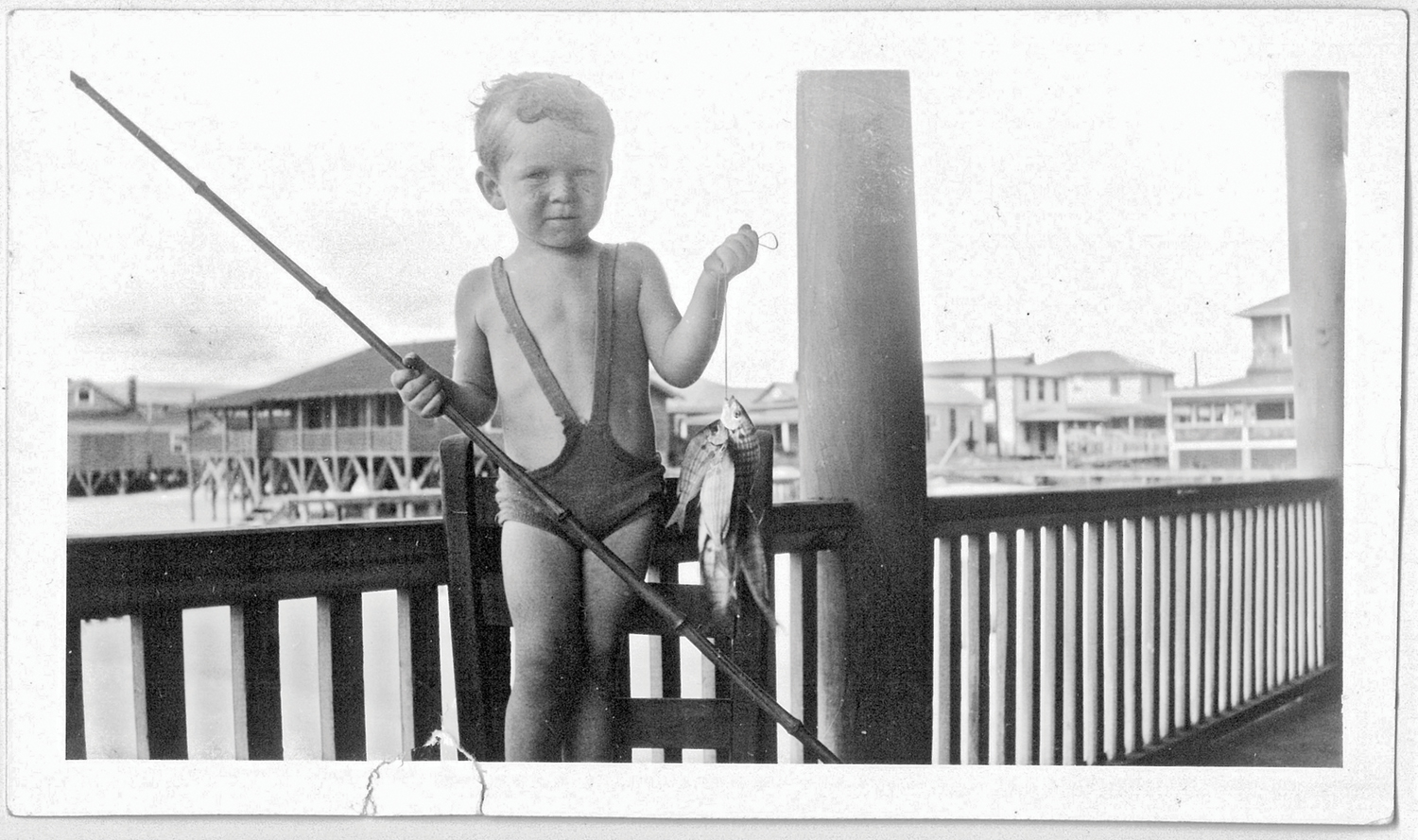

His roots go deep. His parents were George Sr. and Sarah. George Sr. served in combat in the Army during World War I alongside other multigenerational Wilmingtonians. George Sr. came home from the war to work in insurance.

“Daddy was in the insurance business,” George Jr. says. “His father was a conductor on the railroad, and his father was the governor of North Carolina during the first part of the Civil War. Henry Toole Clark. Mother was from Lumberton. When her nine months were up, she went back to Lumberton to have me. Horace Baker, the doctor, was a good friend of her family. She had me in Lumberton [spring of 1928] and then came right back to Wilmington and the beach.”

George has never met a stranger. In the late afternoons he enjoys a beautiful sunset view across Waynick Boulevard to Banks Channel.

“That’s another thing about the beach,” he says. “People are so congenial. They’ll stop and talk about the flowers. Sometimes they’ll come up here and have a beer. It’s a friendly sort of situation. I enjoy it. I have a good time.”

One son and family are right next door. Another comes from Raleigh often. Friends come and go constantly.

Ensconced in a chair on his ocean-facing deck looking over South Lumina Avenue, George will speak to everyone who walks by, regardless of age. (I believe that’s how he met this journalist so long ago.)

A few years ago he met a young surfer, Grace Brookshire, the same way. Brookshire walks to the CAMA beach access closest to George’s cottage for surfing after parking nearby.

George invited her to come up for a visit and a friendship formed. She, like so many of George’s friends, enjoys his stories.

“George has a million stories about Wrightsville Beach. He’ll tell you about the time on the Fourth of July as a lifeguard and how they saved so many people, or the story of the jetties,” Brookshire says. “George has become like a grandfather to me; both of my grandfathers have passed away. Relationships matter. I have gotten so much from that relationship.”

There are very few topics that George doesn’t have a story about.

“Have I told you about the time I…?”

Brookshire picked up on an unspoken need for a man who has loved the beach strand and had surf fished his entire life.

“He told me that he hadn’t been out on the beach in a long time because of his knees. I told Dave Baker about it and Dave Baker took the ball and ran with it,” Brookshire says.

Early on a rainy morning in July, before Baker’s elite ocean rescue squad deployed to the strand, they picked up George at home and brought him to the back side of the old fire station, where they held a simple ceremony honoring George for his years as the oldest living lifeguard at Wrightsville Beach.

“It grew really fast,” says Baker, Wrightsville Beach Ocean Rescue (WBOR) director. “Grace approached me through another person and it turns out [the late WBOR Capt.] Jeremy Owens had told George he would take him for a ride. Then we lost Jeremy. And I said, yeah, we’re going to make this happen.”

Baker first picked George up at his house carrying lifeguard swag: hat and T-shirt, which he immediately donned before climbing into Baker’s truck for a ride up the strand.

“George deserves this because he paved the way and set the groundwork for what Wrightsville Beach Ocean Rescue is today,” Baker says. “It was because of him and the others, with the little they had, they were still saving lives and making a difference.”

In the old fire station’s back bay, among the young, athletic present-day lifeguards, most 70 years his junior, George was all smiles. Baker presented George with an orange whistle and a rescue buoy signed by all the lifeguards.

Son George III has hung the buoy over the fireplace in George’s cottage.

“I was really impressed with the guard corps. They are very professional nowadays,” George says.

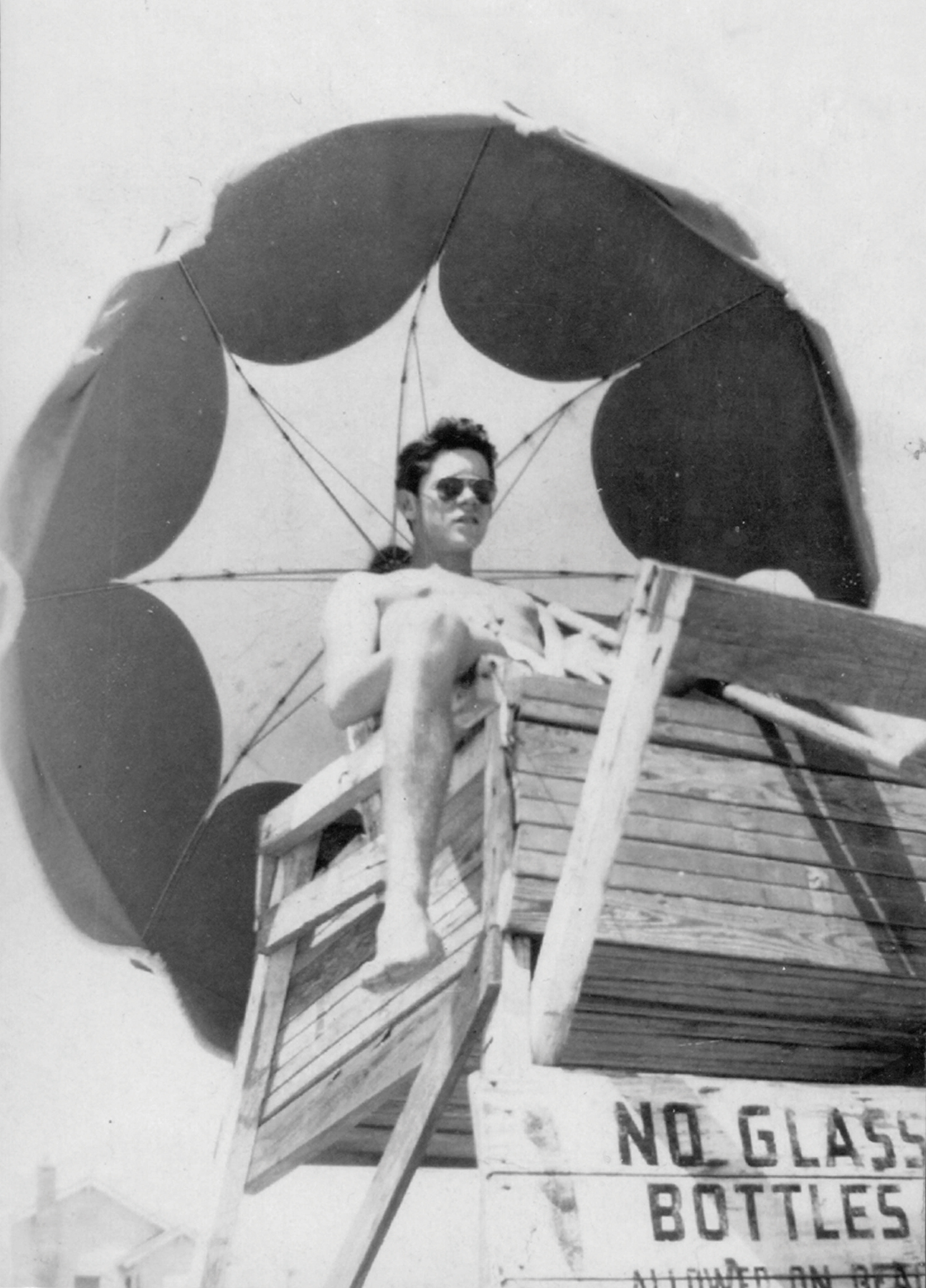

A photo from 1946 shows him sitting in a lifeguard stand shortly after he graduated from New Hanover High School.

“Lifeguarding wasn’t as glamorous as it is thought to be,” he says. “It is probably the most boring job in the world. Because you are not even supposed to be reading. (George is a lifelong voracious reader.) You are supposed to be looking and that is not much fun. The lifeguards in those days, as I specifically recall, we worked for the police department. There were no necessary qualifications. No one had to have first-aid experience or classes or anything like that. In addition, we had no supervision. We came to work when we were supposed to and nobody checked on that or checked when we left. And if it was raining, we went home. But in spite of the looseness, we never had a drowning at any place on the beach that had a lifeguard stand. I think that’s remarkable. That doesn’t mean that we didn’t pull a lot of people out of the surf, because we did. I remember one Fourth of July we pulled 30-something people off of the jetty at Birmingham Street,” George says.

Baker says the current squad is mostly 20ish.

“The purity of what we do has not changed since lifesaving began in the 1800s, it is man against the ocean, saving a life. That’s it, that part has not changed,” Baker says.

The WBOR has just successfully defended its title as the United States Lifesaving Association’s South Atlantic Regional champions.

George described it as an impressive day, a wonderful day. The young guards also enjoyed their time together.

“The crew was so excited and loved it. George made a difference to them. What you’re seeing is living history. They [the squad] are seeing themselves 70 years later, he did what they are presently doing at about the same age,” says Baker.

Ocean Rescue Captain Sam Proffitt drove George north to south along the strand after the ceremony and then home.

“I was thrilled at that,” George says. “I’ve seen all parts of the beach over my many years, like a jigsaw puzzle, but I had never seen it all at once.”

Thank you George Jr for writing the memoir on the commercial fishing issue depleting our resources. I agree that all the recreational fisher people will need to bond together with a fishing platform to elect our legislators with. Sarcastically, speaking there are enough of North Carolinian fisher people to maybe bribe or pay off whomever is being paid off currently to aid and abet the commercial netting industry. I’m pretty sure we out number them 100,000 to 1 and probably could fund the bribery better than they are being paid now. It’s a sarcastic joke but may be the only way since money usually talks. I am happy for George and his era of fishermen who had the please to see and catch fish back when it wasn’t over-netted. We really need to do something especially like other states not allowing netting up in the sounds/estuaries. Maybe the government can pay off the commercial fishermen like the paid the farmers not to grow certain crops and actually supervise it better. We to stop other States and International boats from coming into NC waters and pillaging our marine resources. It’s kind of a no-brainer as George put it. Also, I would guess that giving money to CCA could hurt, so all you fisher people in NC come off of that money if you can spare a donation.