june 2022

“HE never spoke about the

war,” says his son, also

named Harry. “But I’ll

always believe the doctors

were right. In fact, the only time he came

close to discussing the war was when I was

in Naval ROTC at the University of North

Carolina. I was about to be commissioned

as a naval officer and was applying to flight

training in Pensacola. I remember telling

him I hoped to become a Navy pilot. He

did what he could to discourage me —

advising against it, but saying little more

than it was ‘dangerous.’”

Decades later, Harry Bethea Jr, began

searching for answers to the questions he

never asked and the stories his father

never told.

Marie Bethea had remar-ried,

and she and her new

husband had cleared the

attic in the family home

of Harry’s papers, photos

and war memorabilia. The

only avenue left was to

contact the VA for copies

of Harry’s military records.

As countless sons and

daughters of veterans discov-ered,

in 1973 a massive fire at

the National Personnel Records

Center in St. Louis destroyed most of

the records for veterans discharged

between 1912 and 1960, including

Lt. Bethea’s.

About all that survived was the

former lieutenant’s dates of service,

a list of his 21 combat missions,

and the medals he received. They

included a Bronze Star, an Air

Medal, and a Distinguished

Flying Cross. The latter may have

been awarded for Lt. Bethea’s

mission on July 31, 1944, his

last. An after-action report and

a newspaper article in The Stars

and Stripes noted his B-17 encoun-tered

heavy anti-aircraft fire, which

tore into the nose and underbelly

and wounded Lt. Thomas McKen-zie,

the bombardier. McKenzie

fought off unconsciousness.

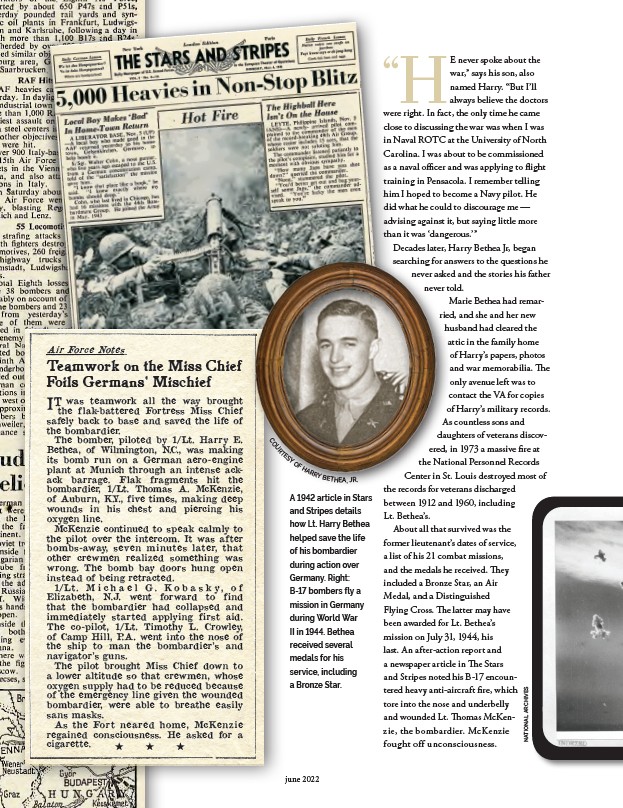

A 1942 article in Stars

and Stripes details

how Lt. Harry Bethea

helped save the life

of his bombardier

during action over

Germany. Right:

B-17 bombers fly a

mission in Germany

during World War

II in 1944. Bethea

received several

medals for his

service, including

a Bronze Star.

Air Force Notes

Teamwork on the Miss Chief Foils Germans’ Mischief

I T was teamwork all the way brought

the flak-battered Fortress Miss Chief

safely back to base and saved the life of

the bombardier.

The bomber, piloted by 1/Lt. Harry E.

Bethea, of Wilmington, N.C., was making

its bomb run on a German aero-engine

plant at Munich through an intense ack-ack

barrage. Flak fragments hit the

bombardier, 1/Lt. Thomas A. McKenzie,

of Auburn, K.Y., five times, making deep

wounds in his chest and piercing his

oxygen line.

McKenzie continued to speak calmly to

the pilot over the intercom. It was after

bombs-away, seven minutes later, that

other crewmen realized something was

wrong. The bomb bay doors hung open

instead of being retracted.

1/Lt. M i ch a e l G . Ko b a s k y, o f

Elizabeth, N.J. went forward to find

that the bombardier had collapsed and

immediately started applying first aid.

The co-pilot, 1/Lt. Timothy L. Crowley,

of Camp Hill, P.A. went into the nose of

the ship to man the bombardier’s and

navigator’s guns.

The pilot brought Miss Chief down to

a lower altitude so that crewmen, whose

oxygen supply had to be reduced because

of the emergency line given the wounded

bombardier, were able to breathe easily

sans masks.

As the Fort neared home, McKenzie

regained consciousness. He asked for a

cigarette.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

COURTESY OF HARRY BETHEA, JR .