TREE OF HEAVEN Ailanthus altissima

They would be almost magical if they were not so pernicious. Seeds encased

in pink, papery wings ride the wind and glide far away from the mother tree,

helping Tree of Heaven invade new territory quickly. It thrives where other plants

struggle, taking root despite poor soil and air quality, displacing native species,

and growing over 80 feet high.

Tree of Heaven secretes an allelopathic chemical into the soil that kills surround-ing

vegetation and prevents other plants from growing. Young seedlings can be pulled up

by hand when the soil is moist, but trees larger than half an inch in diameter will require

targeted herbicide application.

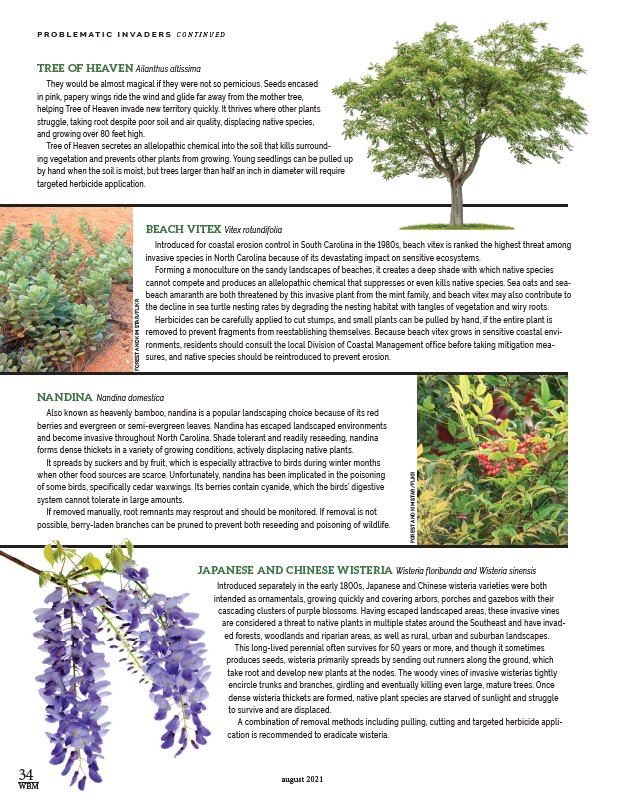

JAPANESE AND CHINESE WISTERIA Wisteria floribunda and Wisteria sinensis

Introduced separately in the early 1800s, Japanese and Chinese wisteria varieties were both

intended as ornamentals, growing quickly and covering arbors, porches and gazebos with their

cascading clusters of purple blossoms. Having escaped landscaped areas, these invasive vines

are considered a threat to native plants in multiple states around the Southeast and have invad-ed

forests, woodlands and riparian areas, as well as rural, urban and suburban landscapes.

This long-lived perennial often survives for 50 years or more, and though it sometimes

produces seeds, wisteria primarily spreads by sending out runners along the ground, which

take root and develop new plants at the nodes. The woody vines of invasive wisterias tightly

encircle trunks and branches, girdling and eventually killing even large, mature trees. Once

dense wisteria thickets are formed, native plant species are starved of sunlight and struggle

to survive and are displaced.

A combination of removal methods including pulling, cutting and targeted herbicide appli-cation

is recommended to eradicate wisteria.

august 2021

P R O B L E MAT I C I N VA D E R S C O N T I N U E D

BEACH VITEX Vitex rotundifolia

Introduced for coastal erosion control in South Carolina in the 1980s, beach vitex is ranked the highest threat among

invasive species in North Carolina because of its devastating impact on sensitive ecosystems.

Forming a monoculture on the sandy landscapes of beaches, it creates a deep shade with which native species

cannot compete and produces an allelopathic chemical that suppresses or even kills native species. Sea oats and sea-beach

amaranth are both threatened by this invasive plant from the mint family, and beach vitex may also contribute to

the decline in sea turtle nesting rates by degrading the nesting habitat with tangles of vegetation and wiry roots.

Herbicides can be carefully applied to cut stumps, and small plants can be pulled by hand, if the entire plant is

removed to prevent fragments from reestablishing themselves. Because beach vitex grows in sensitive coastal envi-ronments,

residents should consult the local Division of Coastal Management office before taking mitigation mea-sures,

and native species should be reintroduced to prevent erosion.

FOREST AND KIM STAR/FLIKR

NANDINA Nandina domestica

34

WBM

Also known as heavenly bamboo, nandina is a popular landscaping choice because of its red

berries and evergreen or semi-evergreen leaves. Nandina has escaped landscaped environments

and become invasive throughout North Carolina. Shade tolerant and readily reseeding, nandina

forms dense thickets in a variety of growing conditions, actively displacing native plants.

It spreads by suckers and by fruit, which is especially attractive to birds during winter months

when other food sources are scarce. Unfortunately, nandina has been implicated in the poisoning

of some birds, specifically cedar waxwings. Its berries contain cyanide, which the birds’ digestive

system cannot tolerate in large amounts.

If removed manually, root remnants may resprout and should be monitored. If removal is not

possible, berry-laden branches can be pruned to prevent both reseeding and poisoning of wildlife.

FOREST AND KIM STAR/FLIKR