Fruit Cake

It is the most British of baked goods —

and the punch line of many holiday jokes.

However, when done right, the much

maligned, iconic Christmas cake is delicious.

As with all good things, fruitcake takes time

and should be made at least one month in

advance of serving. This allows the cake to

deepen its flavors because the fruit contains

tannins that are released over time. Its longev-ity,

lasting for months without going bad, is due to its moisture-stabilizing properties, mainly sugar. The high den-sity

of sugar reduces the cake’s water content, and therefore its ability to bind to bacteria.

History and lore are intertwined when it comes to fruitcake. Ancient Egyptians placed versions of fruitcake on the

tombs of loved ones as food for the afterlife, while an ancient Roman recipe, consisting of pomegranate seeds, pine

nuts, raisins and barley mash, seems to be the oldest.

Around the Middle Ages, honey, fruit and spices were added to the cake. Crusaders were reported to have carried

cakes of embalmed fruit to sustain them on long journeys. It was during this time that the name “fruitcake” was first

used. By the 1400s, the cakes became heavier and more laden with dried fruit imported from the Mediterranean to

Britain. Originally raised with yeast, by the 1700s, the loaves were raised with eggs.

There are various theories about how fruitcake became tied to the holiday season. Some

believe it was because English citizens passed out fruitcake slices to the poor women who sang

Christmas carols on the streets of London in the late 1700s.

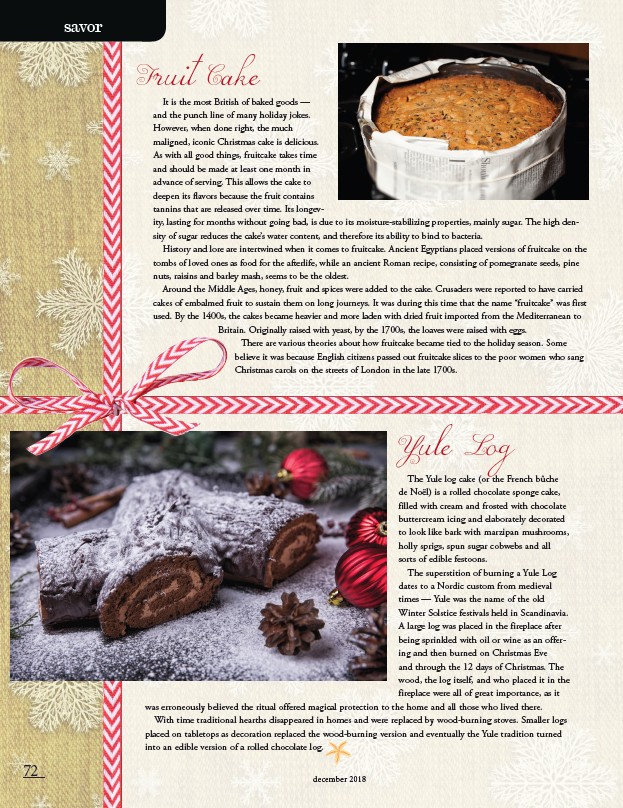

Yule Log

The Yule log cake (or the French bûche

de Noël) is a rolled chocolate sponge cake,

filled with cream and frosted with chocolate

buttercream icing and elaborately decorated

to look like bark with marzipan mushrooms,

holly sprigs, spun sugar cobwebs and all

sorts of edible festoons.

The superstition of burning a Yule Log

dates to a Nordic custom from medieval

times — Yule was the name of the old

Winter Solstice festivals held in Scandinavia.

A large log was placed in the fireplace after

being sprinkled with oil or wine as an offer-ing

and then burned on Christmas Eve

and through the 12 days of Christmas. The

wood, the log itself, and who placed it in the

fireplace were all of great importance, as it

was erroneously believed the ritual offered magical protection to the home and all those who lived there.

With time traditional hearths disappeared in homes and were replaced by wood-burning stoves. Smaller logs

placed on tabletops as decoration replaced the wood-burning version and eventually the Yule tradition turned

into an edible version of a rolled chocolate log.

savor

72 december 2018