Five-O-Fives Return to Normandy

Dr. Daniel B. McIlvoy Jr. is among those honored at a D-Day ceremony on June 6, 2024

BY WBM Staff and Rona Simmons

Unless we had a grandparent, parent, uncle, aunt, or cousin who was there, most of us learned of D-Day from the pages of a history book or through the movies. Our first inkling of one of the pivotal events of World War II might have been Henry Fonda commanding the 4th Infantry Division across the beaches or John Wayne in the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in the 1960s saga The Longest Day. It may have been the all-too-real 27-minute opening scene of the 1990s film Saving Private Ryan, where Tom Hanks and the 2nd Ranger Battalion fought to establish a beachhead.

Each year on June 6 we honor the memory of the 160,000 allied troops who landed in 1944 on the beaches of Normandy, France, in the largest seaborne invasion in history. We honor the 2,500 who perished during the hours and days that followed. If we are fortunate, one day we might visit the hallowed ground of Normandy.

This year, on the 80th anniversary of D-Day, 100-year-old veteran Jack Kraczewski from Pulaski, Wisconsin, was there, as was 101-year-old Jack Larson from Martinez, California, and 104-year-old Edward Berthold from Chicago, Illinois.

The three centenarians joined other Normandy invasion survivors, families, and world leaders to commemorate what was the turning point of the war.

On June 6, 1944, Kraczewski drove ashore as part of a mobile anti-aircraft unit while Larson, after stepping from his landing craft, held his rifle high overhead and waded to the beach through neck-deep water. Berthold had a different vantage point. The copilot of a B-17 bomber, his mission was to bomb a bridge in the town of Saint Lô, France.

Tens of thousands attended ceremonies this year. They came by air, ship, car, bus, or walked. They gazed up and down the coast, guidebooks in hand, cameras panning left and right, guides chattering away as they proceeded from Sword, Juno, Gold, and Omaha beaches to Utah Beach. Some stooped to gather a fistful of the copper-colored sand on which the battle took place.

This year, among the throngs carrying their memories forward were Mary-Ann (Annie) McIlvoy Zaya, Linda McIlvoy Penn, and Carol McIlvoy Kersting, the three daughters of Col. Daniel B. McIlvoy, battalion and regimental surgeon for the 82nd Airborne, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The sisters, born one year apart, are 75 to 77 years old.

This D-day visit was particularly special for the family. McIlvoy, who served a pediatric residency at Babies Hospital and became a part-time Wrightsville Beach resident, was honored posthumously along with the medics of the 82nd/505th with a permanent plaque at La Fière Bridge, an important battlefield near Sainte-Mère-Église, where the 82nd /505th dropped in the town square and fought an intense battle to secure Allied positions inland. It was the first town liberated, near the D-Day beaches.

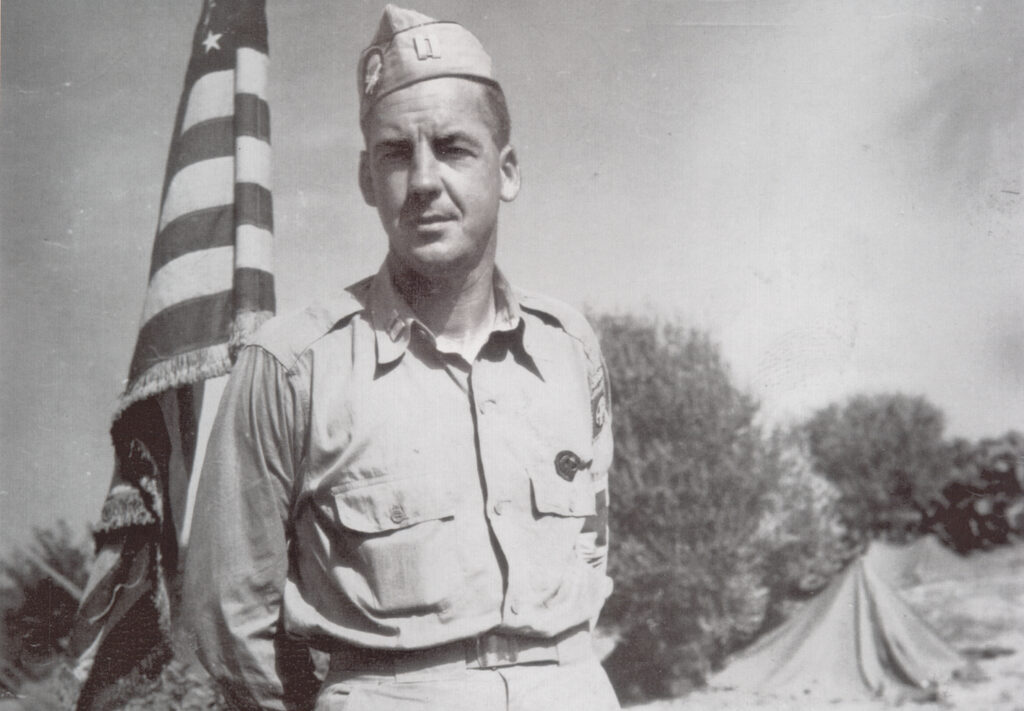

McIlvoy joined the National Guard when he was 17. After graduating from medical school, he was commissioned in the U.S. Army Medical Corps in 1942 as a first lieutenant. He was later assigned to Camp Adair in Oregon as division artillery surgeon.

Homesick for his Kentucky birthplace, he joined the paratroopers, which took him to Georgia. At 30 years old McIlvoy was assigned to the 82nd Airborne/505th Parachute Infantry Regiment as battalion surgeon. Paratroopers were a new concept, and the 82nd was not only the first airborne division in the history of the U.S. Army, but also recognized as one of the bravest.

He deployed to North Africa with the 505th, crossed the coast to Tunisia, and arrived in Sicily at the beginning of the Italian campaign. Soon, the Army sent the 505th to England to train for the upcoming invasion of France. McIlvoy helped train others in field medical procedures.

Now a major, he found himself in the thick of the action. McIlvoy, with little more than his medical supplies on his back, jumped into the Normandy area with the 505th Parachute Infantry on D-Day. With two jumps under their belts at Sicily and Salerno, Italy, the 505th successfully landed near their drop zone and eventually liberated Sainte-Mère-Église.

For 33 days the regiment faced heavy fighting and casualties. McIlvoy and his medics turned a house into an aid station to tend to the hundreds of wounded soldiers. Medics marked the house with Red Cross signs and were astonished when the Germans allowed them out at night to gather up wounded American soldiers.

In a 1988 interview, McIlvoy, then a 76-year-old retired pediatrician, remembered John Steele, an American paratrooper from Wilmington/Wrightsville Beach whose parachute snagged on a church steeple in Sainte-Mère-Église. Steele hung there pretending to be dead so the Germans wouldn’t kill him. When it was safe, he was freed from his parachute and reunited with his company.

After their last combat jump in Holland, the 505th entered the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium and Luxembourg from Dec. 16, 1944, to Jan. 28, 1945. It was the largest land battle of the war in which Americans would participate. Historical accounts record that more than a million men fought in the battle, including 600,000 Germans, 500,000 Americans and 55,000 British. It would end with 75,000 Americans wounded and 19,000 killed.

According to the many accounts of McIlvoy’s efforts, he saved many lives through his medical skill, training less experienced medical officers, and developing a triage system amid the chaos of battle.

McIlvoy parachuted into Sicily, Salerno, Normandy, and the Netherlands. He was one of only three medical officers to make four jumps, author John Ospital wrote in We Wore Jump Boots and Baggy Pants.

He received the Legion of Merit (Combat), Bronze Star Medal with oak leaf cluster, and Purple Heart with cluster for wounds received in Sicily and the Netherlands. He also received a Citation for Gallantry in Action from the 82nd Airborne Division.

He was remembered too for work behind the front lines. In a story that has become legend, while in Normandy he rendered medical aid to a young Frenchwoman as she gave birth to a son, later named Daniel in McIlvoy’s honor.

After the war, the newly married McIlvoy did his pediatric residency under Dr. J. Buren Sidbury at Babies Hospital, across the sound from Wrightsville Beach, in 1946. He and Pauline (Polly) moved into a rental on Harbor Island. Polly worked as a secretary at the Wilmington shipyard.

The young couple grew fond of the beach community. After his one-year pediatric residency, McIlvoy launched a thriving career in his hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky, but the family spent summers at Wrightsville Beach for the next 50 years. In 1974, they purchased the old green-shuttered West Atlanta Street home of Lester and Mickey Newell.

“He loved the beach,” Annie says of her father. “I was born in 1946 and every year of my life went to Wrightsville Beach. At night we’d all go crabbing, and then we’d let them go and they’d run all over our feet. And we’d sing on the front porch, songs like ‘Shine On Harvest Moon.’ My uncle would play guitar. And we’d fish on the pier.”

From March to October, the family lived in Wrightsville Beach while other family came and went during the summer months. After October, they would pack up their bathing suits and return to Kentucky for the rest of the year.

It was there they docked their boat, the Polly B., and the place where grandchildren experienced Wrightsville Beach. In September 2002 they sold the home, which was later demolished to make way for a new duplex.

McIlvoy’s patients and friends knew him as Doc, a name given by fellow soldiers who admired him for his brave and tireless work. His family remembers him as a quiet, gentle man. He didn’t talk about the war with his young children, but later, as a bed-stricken man, the stories were shared with Annie, now an adult. She began to understand that her father was a hero. It wasn’t that he talked about himself, she said, as much as he talked about the courage of the men with whom he served.

“He had a stroke in 1996. He was quite homebound, and that’s when he showed me his pictures,” Annie says. “I didn’t realize how important this was to him. It was emotional for him.”

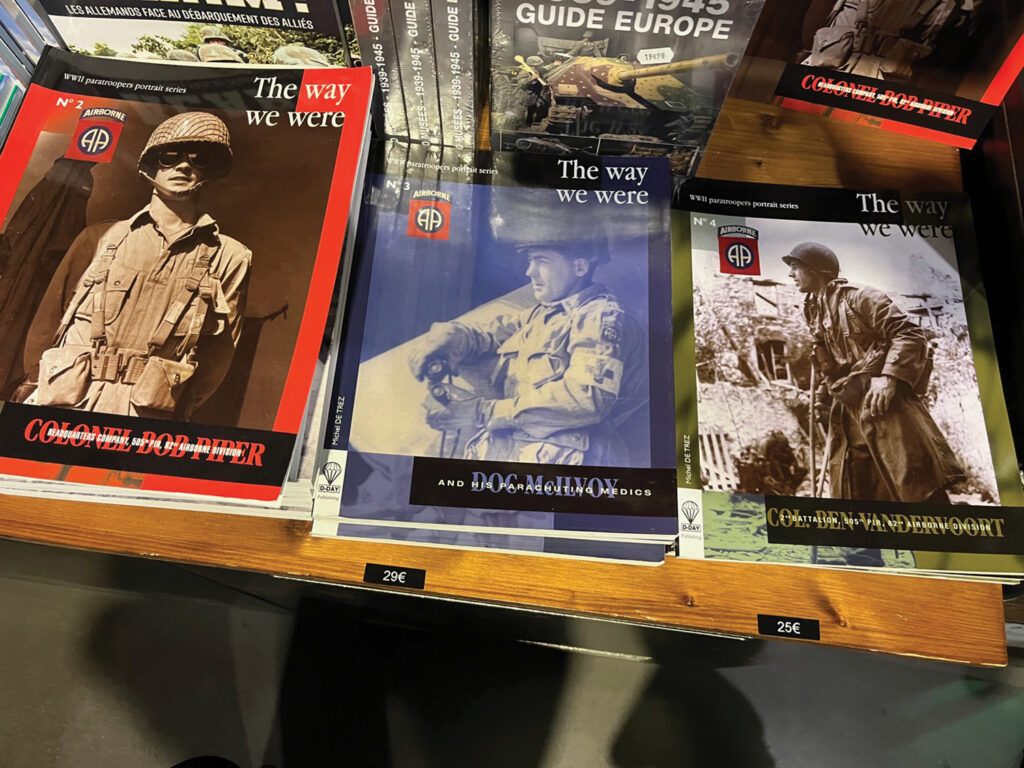

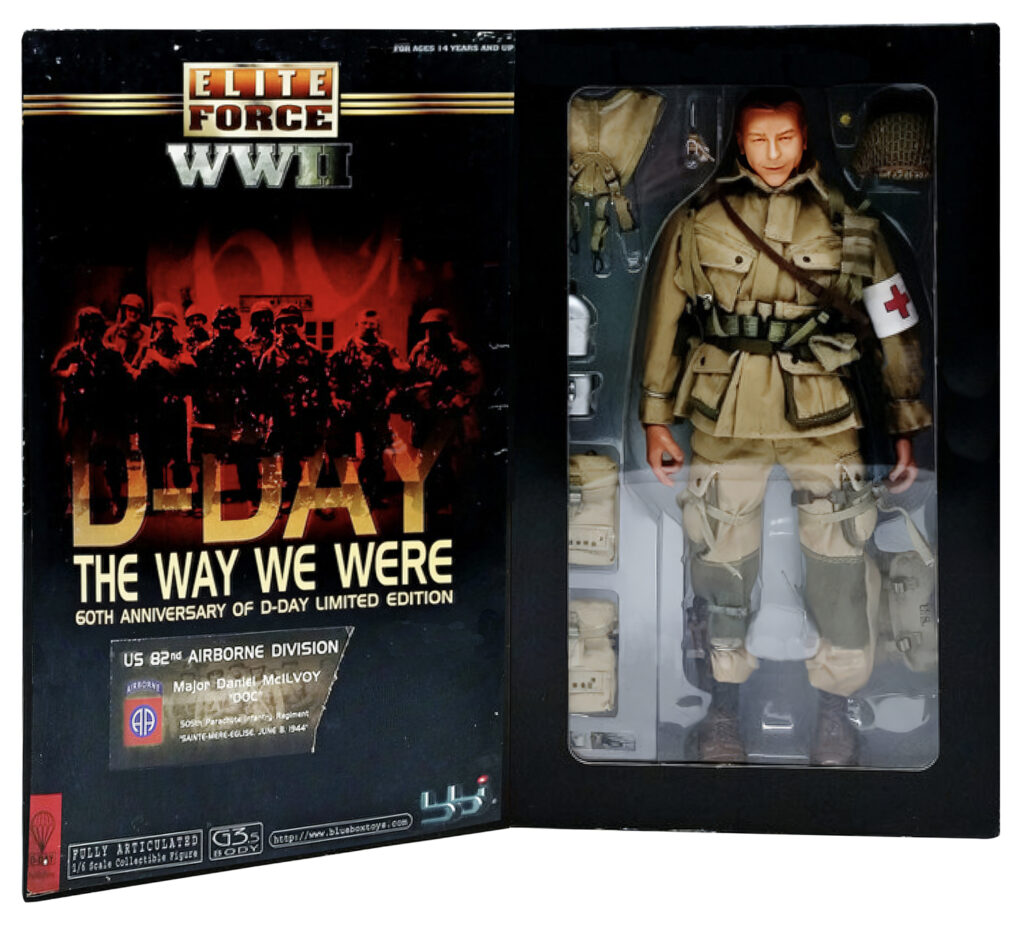

He passed away in 1998 in his Kentucky hometown at the age of 85 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with the highest military honors. His story has been told many times, notably in Doc McIlvoy and the Parachuting Medics (2004) the third book in The Way We Were, a series of portraits published by Michel De Trez. A 12-inch D-Day action figure of him with accessories was created for the release of the book.

Annie donated an Elite Force World War II U.S. 82nd Airborne D-Day Major Daniel McIlvoy action figure to the Wrightsville Beach Museum in the 1990s.

Some sections of text appeared in the Wrightsville Beach Magazine, June 2004 issue entitled In Remembrance of a Hero: Doc McIlvoy by Gretchen Nash.

The Book:

Doc McIlvoy And His Parachuting Medics

When author Michel de Trez called Annie McIlvoy Zaya in 2003 about writing a book on her father’s experiences as a medic, she was relieved. The memoirs, conversations, stacks of articles and books, and Doc’s story would finally be compiled into a book that recognized McIlvoy and the medics for their devotion to the soldiers of WWII. The 2004 publication of the book Doc McIlvoy and His Parachuting Medics coincided with the 60th anniversary of D-Day. It is respectfully dedicated to Dr. Pete Suer.

De Trez is the author of five books about American paratroopers, a producer of WWII documentaries, and researcher of WWII airborne equipment and history.

I meet DocS three daughters in Normandy on June 5th this year while I was serving as the 505th senior medic. I was really moved by them and the love they have for their father.

If anyone can help me reach out to them I would greatly appreciated it

SFC Chase B Johnson

Senior Medic

307th Airborne Engineer Battalion

3rd BCT 82nd Airborne