Endangered Species

BY Amy Kilgore Mangus

Oh Masonboro My Masonboro

I love thy every hill

I love thy every tree and path

thy every daffodil

I love the rustic beauty of thy

enchanting shores

I love thy mystic timeless way of life

and with its lore

So rich from times of old.

— Excerpt from My Masonboro

by William A. Hurst 1956

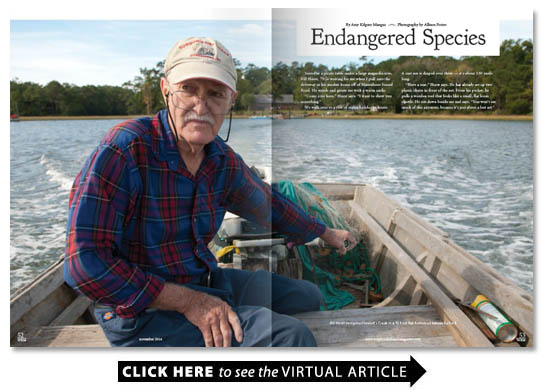

Seated at a picnic table under a large magnolia tree Bill Hurst 79 is waiting for me when I pull into the driveway at his modest home off of Masonboro Sound Road. He stands and greets me with a warm smile.

Come over here Hurst says. I want to show you something.

We walk over to a row of stakes beside the house. A cast net is draped over them — it s about 130 yards long.

Have a seat Hurst says. He has already set up two plastic chairs in front of the net. From his pocket he pulls a wooden tool that looks like a small flat loom shuttle. He sits down beside me and says You won t see much of this anymore because it s just about a lost art.

There s a large hole in the cast net. Using the shuttle wrapped in monofilament his long fingers thread it through the hole creating a diamond pattern. He does this a few more times. The hole is getting smaller and smaller.

This was one of the first trades I ever had way back when I was a boy. People don t have the patience to do this nowadays. And we live in a use-it-once-and-throw-away society.

This net is about 15 or 20 years old and Hurst says it s really not worth fixing. But he says It s been a good run and caught a lot of fish. I m not gonna junk it just yet.

Hurst was 5 years old when his family was forced to move from Onslow County. The federal government needed the Hurst land a 1 1/2 mile stretch of beachfront

to build Camp Lejeune.

Hurst s mother Betty was a Hewlett whose ancestors lived in the rural Masonboro Sound farming and fishing community long before the Civil War. They relocated to a rented farmhouse on the sound. The shipyard was starting and his father Adrian Hurst was a math professor — the first one ever hired at Wilmington College now the Universtity of North Carolina Wilmington in 1947.

Soon Adrian purchased a 3 1/2 acre soundfront tract of land. During World War II no houses were being built in the county because the government froze building materials for military use. After his permit was denied Adrian begged for reconsideration. Since he worked at the shipyard he was able to get heavy form lumber after it was used. Delivered with big trucks it was dumped on the property. His father utilized German prisoners of war who worked at a local dairy farm in town to pull nails from the wood using hammers and crowbars to separate the lumber. Adrian then hired Lesmon Hansley a carpenter and the two built the Hurst family home. It had no electricity.

When we moved in it was nothing but rough subfloor. And my youngest sister was in diapers and she would drag those diapers over this old floor and they d be just as dark as your shirt Hurst says with a laugh. After the war finish work like the addition of oak flooring was completed.

Bill Hurst inherited a portion of his mother s land on Hewlett s Creek.

I could never in a hundred years make enough money to afford this property here if it hadn t been in the family he says. He and his wife cleared the land built a road and built their home moving in during spring 1976. The house his father built is just one mile away and now owned by his sister Patsy.

Hurst learned many trades growing up along Hewlett s Creek.

If you grew up in a rural environment when I did you learned to farm you learned to build you learned to fish you just learned to do all these things because it was a different world back then he explains. You learned mainly because you were simply exposed to it. You learned how to cut down trees and cut firewoodhow to take care of animals chickens hogs.

After graduating from Wilmington College Hurst was a medical laboratory technologist at James Walker Memorial Hospital. He then worked at Cape Fear Technical Institute and served as a consultant for the State Board of Community Colleges in the fisheries division. He taught marine-related skills like net mending and welding in workshops along the coastal counties. To this day Hurst has a close relationship with local marine biology programs and allows students to conduct research from

his property.

Now during his retirement Hurst uses three boats that he personally built to commercial fish mostly in the inlet. He sells to local seafood markets and is licensed to sell shrimp and crab to the public. Hurst says that rules and regulations have affected the commercial fishing industry drastically.

I support reasonable conservation measures like size limits he elaborates.

Hurst says his father was a conservationist before the term was coined.

He firmly believed that if you really messed up Mother Nature you were going to pay a dear price. Maybe not that generation but maybe by the next generation. And this has been very true Hurst says. We don t have near the fish we used to have. I remember when five of us made a haul of 13 000 pounds of mullet in one haul. You ll never do that again.

However Hurst is concerned rule makers don t have fishing backgrounds.

We have invested in all this equipment and then at the stroke of a pen they will tell us you can t catch this and you can t catch that. Now if they would tell us a year ahead of time we wouldn t be preparing our nets and such he explains.

Still Hurst fishes every day. He goes out with the rising tide fishes the high water and comes back on the falling tide. Before outboard motors fishermen did the opposite.

They would go out on the falling tide drifting with it and fish on the low water turn around and fish their way back in on the rising tide. On the low tide the fish are concentrated because there s less water. On high tide the fish can scatter he explains. It s just now time for fish to start migrating the mullets bunch up in schools and come down jumping the spots should be running strong. And when it gets real cold speckled trout and puppy drum come in.

Accustomed to always working with his hands when not fishing he makes cedar chests and baskets out of grapevines from his property. His wife of 44 years Lillian says she married an endangered species. But as long as he can he ll fish Hewlett s Creek like his predecessors.

If I wound up dying in my boat I would rather do that than be in a nursing home he says.