Conserving History

BY Kamerin Roth

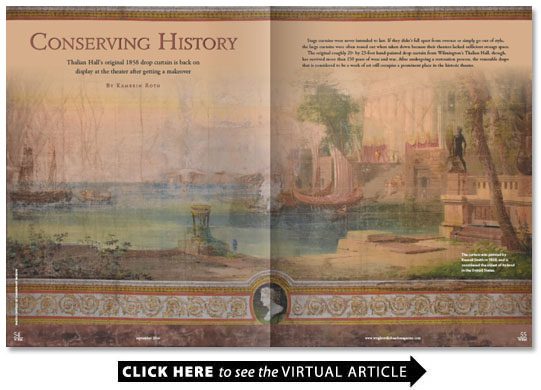

Thalian Hall’s original 1858 drop curtain is back on display at the theater after getting a makeover

Stage curtains were never intended to last. If they didn’t fall apart from overuse or simply go out of style the large curtains were often tossed out when taken down because their theaters lacked sufficient storage space.

The original roughly 29- by 23-foot hand-painted drop curtain from Wilmington’s Thalian Hall though has survived more than 150 years of wear and tear. After undergoing a restoration process the venerable drape that is considered to be a work of art still occupies a prominent place in the historic theater.

The curtain is 150 years old ” says Tony Rivenbark executive director of Thalian Hall. “It was never meant carry out this kind of lifespan but it has survived over the years one way or another.”

Earlier this year the historic curtain made a trip to the Cameron Art Museum where it underwent some much-needed conservation treatment. It was away for several months being repaired and on exhibit before returning home to Thalian.

With around 250 performances in the building each year the same curtain that rose to reveal the very first performance is still a part of today’s theater scene. In July the restored and revived curtain went on display in Thalian’s ground-floor lobby for all of Wilmington’s theatergoers and art lovers to appreciate.

The curtain is considered the oldest of its kind in America painted by noted scenic artist Russell Smith in 1858 the same year that Thalian Hall opened.

When Thalian was built it was the largest theater in the state and served as both a performing arts center and convention center of sorts with a myriad of activities. During the first year the curtain opened for 180 professional performances and some locally produced performances by the Antebellum Thalian Association.

Like many stage artists of his time Smith painted the curtain with a technique referred to as distemper. He used a whitewash of chalk or lime mixed with a gluing agent that allowed the paint to spread and dry to the canvas with a matte-like finish. Because distemper is intended for temporary interior use it is water soluble and extremely fragile. Very few painted stage curtains from the 1800s have endured the test of time. In fact most of the oldest surviving curtains from New England only date back to the 1890s.

Smith loved to incorporate classical themes into his work and the Thalian curtain was no exception. It depicts Greek dignitaries sailing the Aegean Sea to a temple of Apollo for the purpose of sacrificing and consulting an oracle. These consultations usually happened before the opening of the ancient Olympic Games which were held in Olympia Greece from the eighth century B.C. to the fourth century A.D.

When completed Smith’s work was considered a masterpiece.

“The new drop curtain is a perfect gem of art and is worthy an hour’s study and contemplation of its varied beauties ” the Wilmington Daily Herald reported on October 7 1858.

When the 23-foot-tall curtain was hung for the opening of Thalian Hall on October 12 it did not disappoint its first audience. The next day the Wilmington Daily Journal reported the curtain was the occasion of much applause.

“Back then there weren’t so many colored images ” Rivenbark says. “It was a different time period. Today I’m continually surrounded and bombarded with colored images on my computer and phone. But in that time people weren’t used to it. So when they came to the theater at night when most houses were dark and/or asleep they could see this incredible curtain with all its brilliant colors. It was quite a treat. It was an entertaining experience.”

It remained front and center until around 1909 when the theater underwent renovations to widen the stage opening and an ornate proscenium arch was installed across the top framing the performance area. Smith’s beautiful piece of art was now too narrow to be the main drape. News reports of the day say new panels were supposed to be sewn to the sides to fit the new width. Instead it disappeared for more than two decades.

It resurfaced in 1932 when it was discovered in a storage room at the public library and was returned to Thalian Hall.

The theater underwent more renovations in the late 1930s and the curtain was damaged extensively. Theater historian James McKoy detailed the damage in Isabel Williams’ “History of Thalian Hall ” “During the reconstruction of the stage the curtain was put upon the stage floor and construction workers rolled their wheelbarrows over it. More than a third of it was cut to ribbons.”

The upper part which showed mostly sky and the very top of the temple was trimmed and thrown out. The curtain was reduced to around 14 feet in height.

The curtain was misplaced once again in the early 1970s and nearly forgotten entirely. The only evidence of its existence for many years was a photograph from the 1960s. If not for that photo and the Rivenbark’s efforts the curtain would probably still be missing today.

Rivenbark learned about the original curtain when he became executive director in 1979. He was giving a presentation to the Historic Wilmington Foundation that year when he displayed a picture of the curtain and said how sad it was it had disappeared. Juanita Menick president of the Thalian Association approached him after the talk and said she had taken home an old curtain from the theater years before for safekeeping. She had been holding onto the original Thalian Hall curtain all along.

“When I found the curtain it had suffered some water damage and the top had been trimmed and discarded but it was still in great shape ” Rivenbark says.

The curtain was recovered from Menick’s garage and returned to the theater where it was displayed as part of a historic exhibit and used in a musical called “Remembered Nights” performed for Thalian’s 125th anniversary.

After being on exhibition for many years it became clear that work needed to be done in order to preserve this historic treasure.

“The question became what to do with it ” Rivenbark says. “How do we stabilize it and keep it safe?”

In January the curtain was turned over to David Goist an art conservationist from Asheville. Rather than restore the curtain which would involve removing some of the original paint in sections and then repainting it Goist decided to conserve it a process that simply maintains what is left of the curtain.

“What we want to do is respect the artist’s original intent ” says Goist who has always loved original paint even if it’s not perfect. “We don’t want to make the curtain look new. That’s not the goal. We want to use a remedial minimally invasive approach to extend its life in ways that avoid paint loss.”

Before beginning work Goist had to devise a plan on how to transport the curtain to the Cameron Art Museum without inflicting further damage.

“We did a lot of pre-planning for this project and eventually we came up with the idea to roll it ” he says. “So it was carefully moved to the stage at Thalian Hall and rolled into a very wide cardboard tube. It was the best way to minimize wrinkles and protect the paint which it did. It worked out really well.”

Goist then devised a way to suspend the tube off the ground in the moving truck. This helped avoid any increased pressure on the curtain while in transit. When it arrived at the museum — the only local site with sufficient space security and staff to complete the project — it was slowly unraveled and worked on as sections appeared.

“The curtain has been fragile for many years ” Goist explains. “It has seen water exposure and been folded many times over the years which caused surface paint loss in the creases. The curtain itself is essentially made from thin panels of muslin all sewn together and many of these panels had separated and needed to be reattached.”

With the help of staff and volunteers Goist removed and replaced many of the curtain’s old patches rejoined tears and attached new muslin cloth to reinforce the canvas. For the areas affected by darkened tide lines caused by water damage the team used wax pastels and in-painting to avoid covering any of the original paint. They also mended the curtain’s hang support which had grown weak from years of use.

The entire project took around two weeks to complete then was put on display in early February in an exhibition called “Raise the Curtain!” It was returned to its original home five months later.

Smith’s original under-drawings can still be seen on the curtain in certain spots. These are his hand-drawn sketches Goist says. Before he painted the curtain Smith drafted the classical scene in pencil to help guide his brush.

There are also signatures on the back of the curtain. It’s not known who signed it but it was and still is common for casts and crews to sign spaces behind the scenes at theaters to leave their mark. Thalian Hall still has signatures all over the building left throughout the years.

“I’m not sure that the piece can last another 150 years ” Goist confesses. “But the people at Thalian Hall have found a really great spot for it. It’ll be in a climate-controlled area with minimal light risk and be protected from people who will want to touch it. It’s conceivable that the curtain could go another 50 years before it needs more treatment.”

While the curtain underwent conservation efforts local artists Virginia Wright-Frierson Rand Enlow and CAM director Anne Brennanwere commissioned to craft a full scale 19- by 32-foot replica of the curtain the way it originally appeared.