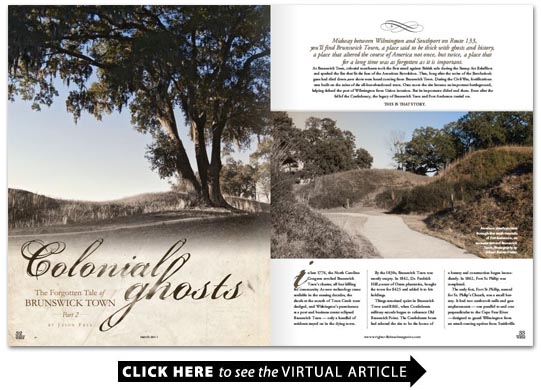

Colonial Ghosts: The Forgotten Tale of Brunswick Town Part 2

BY Jason Frye

Midway between Wilmington and Southport on Route 133 youll find Brunswick Town a place said to be thick with ghosts and history a place that altered the course of America not once but twice a place that for a long time was as forgotten as it is important. At Brunswick Town colonial merchants took the first stand against British rule during the Stamp Act Rebellion and sparked the fire that lit the fuse of the American Revolution. Then long after the noise of the Revolutions guns had died down new shots were heard coming from Brunswick Town. During the Civil War fortifications were built on the ruins of the all-but-abandoned town. Once more the site became an important battleground helping defend the port of Wilmington from Union invasion. But its importance didnt end there. Even after the fall of the Confederacy the legacy of Brunswick Town and Fort Anderson carried on. This is that story. In late 1776 the North Carolina Congress revoked Brunswick Towns charter all but killing the community. As new technology came available in the ensuing decades the shoals at the mouth of Town Creek were dredged and Wilmingtons prominence as a port and business center eclipsed Brunswick Town only a handful of residents stayed on in the dying town. By the 1830s Brunswick Town was mostly empty. In 1842 Dr. Fredrick Hill owner of Orton plantation bought the town for $4.25 and added it to his holdings. Things remained quiet in Brunswick Town until 1861 when Confederate military records began to reference Old Brunswick Point. The Confederate brass had selected the site to be the home of a battery and construction began immediately. In 1862 Fort St. Philip was completed. The early fort Fort St. Philip named for St. Philips Church was a small battery. It had two earthwork walls and gun emplacements one parallel to and one perpendicular to the Cape Fear River designed to guard Wilmington from an attack coming upriver from Smithville (now Southport). The designers incorporated the terrain into the defenses using the surrounding creeks swamps and Orton Pond as barriers against attack but the back of the fort remained open and unprotected. On May 4 1862 William Lamb came to Fort St. Philip from Fort Fisher and significantly modified the earthworks building them up to 26 feet high and 30 feet thick at the base adding five magazines (to store powder and explosives) and nine gun emplacements. For much of 1862 the site housed a Yellow Fever quarantine station and a hospital was built for those quarantined though that didnt slow Lambs progress. In 1863 Fort St. Philip was renamed Fort Anderson after Brigadier General George Burgwyn Anderson. Around 300 men were stationed at Fort Anderson until the 1865 fall of Fort Fisher. After losing Fort Fisher all garrisons on the river south of Fort Anderson were abandoned and their troops took up final defensive positions behind its imposing walls. By the end of January 1865 there were 2 200 troops plus support staff at Fort Anderson. Their orders were to hold the fort at all costs. In early February a flotilla of 15 Federal warships began shelling the fort. By February 11 the bombardment had intensified. Then on February 17 a division of Federal troops under the command of General Jacob Cox marched on the fort from Smithville. They arrived on February 18 and set up camp only 600 yards from the southern wall. The flotilla intensified their bombardment to coincide with the arrival of Coxs division and more than 3 000 shells were fired into the fort that day. Cox split his force into two brigades one remained at the front of the fort; the other flanked Orton Pond to attack the rear at dawn. In a show of bravado Cox paraded his men onto the field before the southern wall and a Federal band played to rally the troops and demoralize the Confederates inside. Not to be outdone a Confederate band in Fort Anderson began to play to bolster the troops on the walls. Shells flew shots were fired and the bands played all day. The intense shelling broke the back of the Confederate command and they decided to abondon the fort. Late in the night on February 18 or early in the morning of February 19 they packed up the essentials and fled. On the morning of the 19th Federal troops poured in from behind only to find the fort deserted. In early 1865 following the end of the Civil War Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson became a refugee camp for recently freed slaves. These freemen were told they had until early summer to be self-sufficient. By mid-May everyone had left the town. The following year two men from the Revenue Cutter Service (now the Coast Guard) went into Fort Anderson on a souvenir hunt. They entered one of the magazines lit a lantern threw the match on the powder-strewn floor and blew themselves up. After that Brunswick Town was largely forgotten and avoided. In the 1890s the Colonial Dames a civic group dedicated to the upkeep of historic sites cleaned St. Philips Church and the cemetery for services and ceremonies honoring colonial and Confederate veterans and dead. From time to time Civil War Veterans would visit the fort. Other than those occasional visits Brunswick Town and Fort Anderson were abandoned. In 1948 a map of Brunswick Town drawn by C. J. Sautier in 1769 was discovered in a British museum. It caught the attention of archaeologist Dr. E. Lawrence Lee a history professor at The Citadel who became interested in Brunswick Town and began to push for preservation and archaeological excavations of the site. Lee got his wish in 1951 when the Episcopal Diocese of Eastern North Carolina and J. Lawrence Sprunt owner of Orton Plantation donated to the State of North Carolina the land consisting of Fort Anderson Brunswick Town and St. Philips Church. In 1955 the Brunswick Town State Historic Site was established under the North Carolina Department of Archives and History. Dr. Lee began archaeological explorations in 1958 and Dr. Stanley South joined him soon thereafter. Archaeological explorations ended in 1968 a year after the Visitor Center opened. No further archaeological work was done on the site until 2007 when plans were underway to install an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant walkway around the site. From 2007 to the ADA walkways completion in 2009 archaeological investigations included ground-penetrating radar of the cemetery and one of the gun emplacements a thorough investigation by Marine Corps Explosive Ordnance Disposal teams and intense excavation of the walkway site itself. More archaeological digs are planned starting in May 2011. In 1995 the site hosted its first Civil War living history event. Now every February they have a Civil War program open to the public. They held their first Heritage Days program in 1996. Heritage Days is a weeklong program for all Brunswick County 4th graders with interpretive and interactive stations showing various aspects of colonial life. The staff is working on adding a second week for 8th graders focused on the Civil War but are waiting for approval from the Board of Education. Like the living history event in February Heritage Days is open to the public but only on the last day. The tale of Brunswick Town and Fort Anderson doesnt end there though and it only gets better. On the morning of February 19 1865 as the Confederate troops fled the battle flag for Fort Anderson fell out of a pack or off the back of a wagon. The next day a Federal soldier from the 140th Indiana Infantry found it and passed it along to his commanding officer Colonel Thomas Brady. Col. Brady kept the flag and in March presented it to Oliver Morton governor of Indiana in a ceremony in Washington D.C. The ceremony held at the National Hotel was well attended and President Lincoln canceled his plans that day to take part. Unbeknownst to Lincoln his change in plans foiled a kidnapping plot by one John Wilkes Booth and some believe sealed his fate. Booth had spent the morning planning a kidnapping and lay in wait for an ambush along the route to Lincolns canceled event. When the president failed to pass by he feared hed been found out learned Lincoln had changed his plans and panicked. He and his co-conspirators fled Booth returning to his room in the National Hotel. At the hotel the first thing he saw was the battle flag of Fort Anderson draped over the balcony. The second was President Lincoln standing over it. Lincoln had given a speech during the ceremony but it is unknown if Booth heard it or not. What is known is that it so incensed Booth that eyewitnesses described the look on his face as “demonical.” Many historians believe this is the moment he abandoned all plans to kidnap the president and began to plot his assassination. A month later Booth struck killing Lincoln in Fords Theatre. The historians at Brunswick Town knew the story but couldnt locate the flag. For years it hung in the Indiana state house but was sold to a private collector in the 1960s. In 2004 the flag reappeared in a Gettysburg Pennsylvania antique shop with a $40 000 price tag. The Friends of Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson raised the money in six months and brought the flag home. Once authenticated and in their possession they let the infamous story be known. With all the talk of the importance of Lexington and Concord and Philadelphia and Boston in the Revolutionary War its surprising to learn the seeds of discontent were sewn here at Brunswick Town. And with Fort Fisher casting a shadow on Fort Anderson its surprising to learn about the battle flag and the role it played in American history. Jim McKee program coordinator of the Brunswick Town State Historic Site calls it “the flag that altered American history.” Today it hangs in the museum alongside placards telling its story and celebrating the work of the Friends of Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson.