Originally published in the August 2001 issue of Wrightsville Beach Magazine.

Who really knows how legends are created? They’re usually remembered as larger than life, but weren’t they mere mortals? What separates them from us?

One thing we do know about the people, the heroes if you will, that become our legends. We know that a common thread runs through most, if not all of their lives. They generally embody the values preached across the globe on Sunday mornings. We observe that they exhibit the traits that Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops recite as a creed. Those of honesty, and kindness, and doing for others, and loyalty. They as a rule never really understand what all the fuss is about. They don’t set out to become heroes. They’re just living their lives, and don’t know any other way to go about doing things.

Eddy Haneman, born on a snowy night in New Jersey in 1920, was such a man. But no one knew him as Eddy Haneman. In Wrightsville he was and will always be just Capt’n Eddy. He was good, kind, reverent, honest, clean, patient, humble and every other good word you can think of.

And then there’s the part about the fish. This man could catch fish. Oh, how he could catch fish. He forever changed the way people fish here; he caught record numbers of fish and will be remembered as THE fishing great, perhaps for all time, and as Johnnie Baker described him, the Ernest Hemingway of Wrightsville Beach.

“Eddy’s life was unusual,” Mary Haneman begins. “Even from his birth, it was different. He was born in a snowstorm, you know, and his father delivered him.”

Just his early days are remarkable. To tell the truth, the stories about his father back in those days sound like legend material too. So Eddy got it honest, as they say, fishing on the old proverbial knee. (Though Mary says he was more like his mother than his father.)

Mary, his petite widow, is still promoting Capt’n Eddy and sharing his beloved memory. It’s what she’s done all her life. She knows no other way. It was her part in their close-knit partnership of marriage and business. Eddy ran the boat, taking the customers out, made sure they caught plenty of fish and had a great time. Mary booked his trips, kept him supplied with bait and blocks of ice, and various other things.

She kept his clothes clean and a hot meal on the table for when he did get home tired and smelly from a huge haul. She often kept the midnight oil burning while he was out late earning their living. She still lives in the solid little house he built for them, the one he called his ‘Peaceful Valley’. It’s tucked behind the neat white fence that Eddy built on Hinton Avenue, which runs between Wrightsville Avenue and Oleander Drive.

How do you tell the story of a man who did so much? Where do you begin, so that younger generations will know this great man, even a little? Perhaps, as always, it’s best to start in the beginning.

When Eddy was just 2, his father bought a 125-foot wooden World War I decommissioned ship. They moved aboard and the regal old ship became home and a floating machine shop for the family for five years.

Unique in its own right, the floating family home held Eddy’s mother’s upright piano, and a spiral staircase. The family headed south in 1927 when Eddy was 7. The boat and machine shop became their base of operation while Eddy’s father built a home in Oriental, N.C., and they moved ashore.

Their house was located on a penwinsula with no bridges, 14 miles from school with no buses to pick him up. Rather than walk the long way round on the narrow dirt roads, Eddy rowed a small boat across the water a portion of the way to school then walked the rest, often in the bitter eastern North Carolina weather. The boat had a small sail, and when the wind was right, Mary says he would sail.

Before school he had cows to milk and chickens to feed. He would frequently deliver the eggs and butter to the people. Then when he was 15, the family made plans to go into the charter fishing business. He, his father and three brothers went into the woods, selected trees, cut them down, and floated them downstream to have them milled for the lumber to build their own boat.

The family left for fishing season in Florida and the Haneman fishing legends began. In the winter of 1935-36, while headed to Florida from Oriental, they stopped off at Wrightsville Beach. There they met Herb Milliken, who told them stories of the fishing they’d been doing here. Back then it was only done inshore and mainly on hand lines; there was no tackle in the area. They were catching blues, mackerel, and blackfish. Their fragile hickory rods and wooden reels wouldn’t hold a big fish, so they used hand lines. But the fishing was excellent, and the family began fishing here each summer until 1941 when the world dissolved into war for the second time.

Early on in those uncertain days the Coast Guard was recruiting men and boats. Having had his captain’s license since he was about 17, Capt’n Eddy joined the U.S. Coast Guard Reserves. At age 21 he ran the boat assigned to the 5th District’s Commandant, described as a “Cadillac of a yacht.” The 5th District’s territory included 156,000 square miles of ocean, bays, rivers, wetlands and tidal marshes, and Capt’n Eddy’s war years were spent patrolling and sweeping the harbors and rivers up and down the East Coast.

The territory included the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays and all their tributaries. There were eight major coastal ports in the district, including Baltimore, Morehead City, Newport News, Philadelphia, Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, Trenton, New Jersey, and both Wilmingtons.

Eddy and Mary were married in 1942, and after the war ended were ready for their own boat. Eddy purchased one of the private boats that had been loaned to the Coast Guard for the war, a 38-foot Matthews that had been new when displayed at the 1935 New York motorboat show before going “in service” at the same place Eddy was. Mary still shudders at the amount of military gray paint they sanded and scraped from every conceivable surface.

“It had forty-eleven coats of gray paint on her,” she exclaims, some 56 years later. “We scraped and scraped and sanded and sanded.”

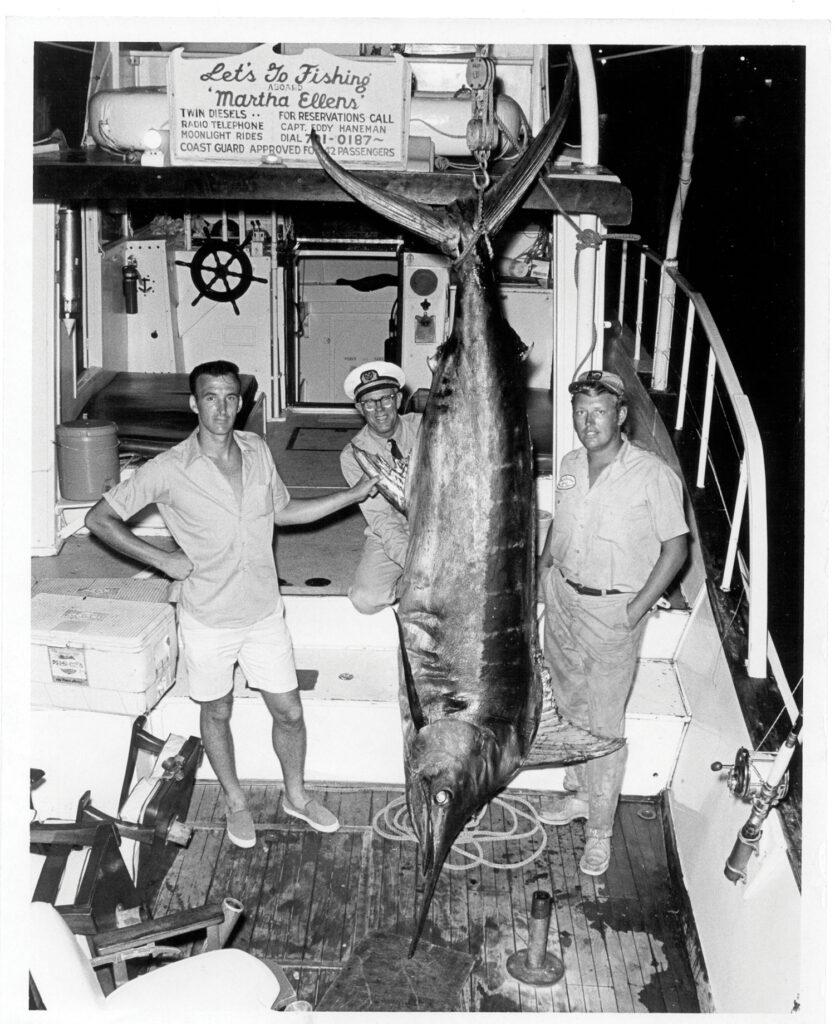

After considerable efforts to convert the boat from its wartime service, the Martha Ellen’s beautiful mahogany and brass shone as bright and new as a copper penny.

“We worked on that boat, Eddy worked and patched on those engines,” Mary says. “It was a massive job. We got her ready for the ’45 season, but he had to work on that boat all the way to Florida, I’d steer and Eddy would work on the engines. In Florida he’d stay up all night sometimes working on those engines.”

Mary has fielded questions about the name of the boat for decades. She relates how Eddy saw the boat first as the Martha Ellen, she had served her country as the Martha Ellen and so she would remain. They went on to have two more boats of that name, the Martha Ellen Too and the Martha Ellens. Ever the economy-minded couple, they didn’t want to have to make up all new signs and brochures.

Mary laughs when she remembers the customers who would call her Martha. Mary once responded with a crack in front of Capt’n Eddy that Martha Ellen was the name of Eddy’s first wife, but she never did it again. Eddy didn’t like it. Mary was his one and only wife.

Reading about the charter fishing business from the years prior to the war, it’s really hard to imagine. The boats were of course wooden. The ponderous craft had little or no amenities.

The smooth sleek marvels of today where guests ride in plush air-conditioned comfort, sipping fresh hot brewed coffee, watching satellite or videos on the cushy ride to the Gulf Stream, were not even a dream then. Boats would pull away from the dock not just before sunrise but the night before, leaving at 8 or 9 p.m. and running into the wee hours to reach the fish. They’d fish all the next day, heading back in time to reach the dock by 9 or 10 at night. It was not uncommon for charter crews in busy times to swap out dirty and empty food and clothes bags and head out once again.

You were expected to catch fish and lots of them, 100 pounders no less. Capt’n Eddy’s philosophy of keeping his customers happy was simple: “Have a good time, come home with a good catch of fish, and come home safely.” And they did. Customers became like family to Mary and Capt’n Eddy as they fished together year after year. Mary would receive cards and letters from out-of-town customers throughout the year.

Fishing was something their customers, both local and from inland rural communities, cities and towns, would look forward to all year long. And Capt’n Eddy was key to those fishing experiences. He stood for excellence in everything he did. Children grew into men fishing with Capt’n Eddy.

After the war ended in 1945 and the boat was made ready for fishing, Mary and Eddy set out on their own wintering aboard the Martha Ellen. They ran charters out of Hollywood, Florida, where Eddy’s success at fishing was also becoming legendary. Mary would spend her days in the car gathering the ice, bait and supplies they needed, always staying busy, waiting for Eddy’s triumphant return to the dock.

Fishing technology became an industry after the war. Sport fishing became the hobby of men. Ernest Hemingway and countless others had made it glamorous and exciting. Outriggers were installed to get lines out further from the boat. Florida was the capital of fishing then and so the newest technology came north with Eddy.

Capt’n Eddy brought back what was being done and what he had learned in Hollywood each winter. In 1946 he began using flexible plastic rods that would break with just the slightest tension. Eddy used silk threads to wrap them and keep them from breaking. He pioneered much in those days. He was the first here to fish with the wire lines that would reach deeper into the sea for bigger fish. He brought tackle north with him too, and during the summers he set up a small tackle shop in their home.

Mary, back at home with her ear on the region’s only ship-to-shore radio, became the source for fishing and weather information. Ever the promoter, when he was heading back in with a back-slapping crew of fishermen and boat full of fish, Eddy would call Mary on the radio and she would alert the media and local people, so when they arrived back at the dock large crowds would be waiting. Sometimes 500 people was not uncommon.

The Martha Ellen also had the first navigational equipment in the area. Before this, 10 miles out was as far as anyone had gone to fish. With the advent of new technology, new places to fish were discovered. Eddy is credited with finding the spot known as WR4, with its wreck and natural shelves. Others followed.

Eddy began shipping ballyhoo in from Florida for bait. He and Tommy Willis made buoys out of tanks and used them to mark the fantastic locations they had found. Developed for the war effort, the early Lorans became available to the public and fishermen embraced these early behemoths with a vengeance.

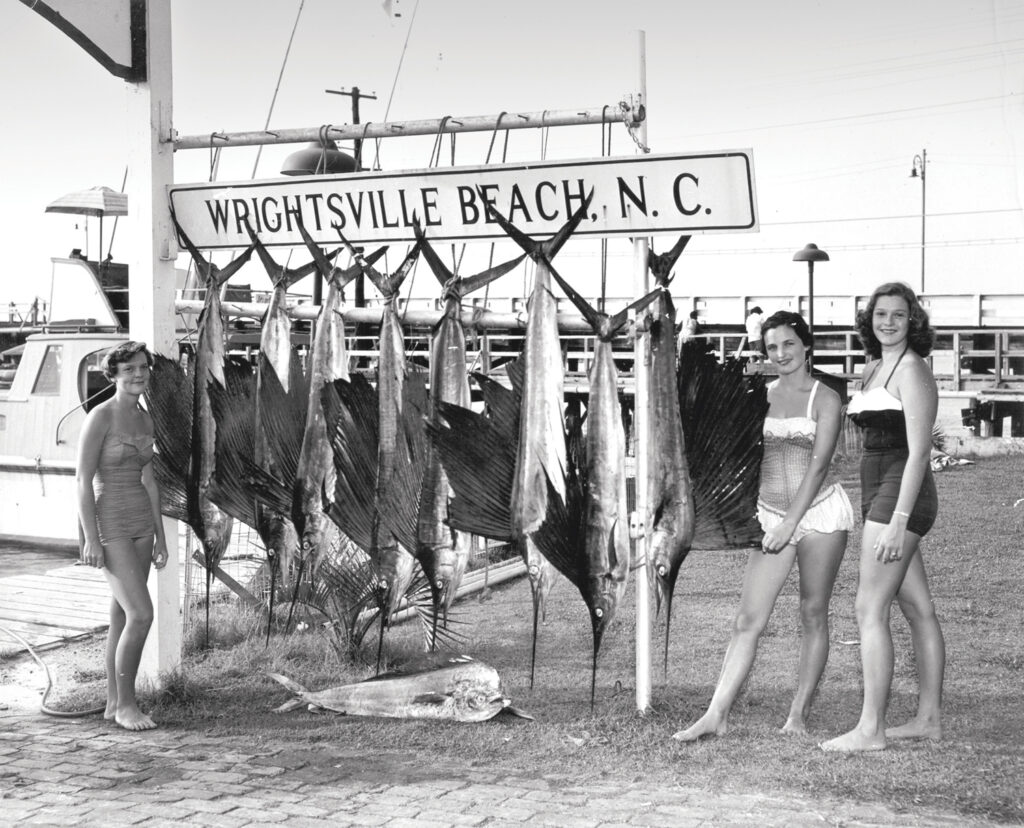

The year of the sailfish bonanza was 1954. This was before Hurricane Hazel, and Mary says the fish were plentiful, freaky even. The stories and photos of the run on these billfish are unforgettable. In just one day 127 were caught. Everyone caught them, even fishermen on piers. Practically everyone who caught one wanted it mounted, and in addition to his growing wholesale tackle business, Eddy picked up another fishing sideline, becoming Pflueger’s North Carolina representative, and 120 of those 127 sailfish were mounted.

Mary and Eddy had a son, who learned to fish with his father at an early age. Their lives revolved around charter fishing and building custom rods. To get set up, in 1947 Eddy and other townspeople wanted a Wrightsville Beach town dock constructed at the corner of the new highway bridge over Banks Channel, but Town officials were having none of it, Mary said, not wanting the fishermen there. They finally struck a deal with Eddy to let him build a dock with his own money on the old trestle pilings parallel to the bridge, then they’d swap out his rent at “their” dock for his efforts.

The boats dropped anchor, backed up to the abandoned trolley bridge, tying up stern-to the new dock. Soon giant grouper, mackerel, snappers and fish of every kind were being unloaded by the boatload and cleaned at this new municipal dock. By the mid-1950s the fishing at Wrightsville was so hot, Eddy and Mary stopped moving the boat to Florida for the winter.

No one can remember seeing Eddy without his white captain’s cap, narrow black tie and uniform khakis. The hat and uniform became his signature. His uniform shirts and pants would get fishy, especially his long sleeve cuffs when those record catches were cleaned after each trip. Mary can still remember the smell and how even the perfectly clean shirts would often have a delightful aroma when she set a hot iron on them. She still doesn’t eat a lot of fish.

“Work is all we’ve ever known,” Mary says of their lives, “From when he was a little boy work was all Eddy ever knew. To waste time to him was a sin, to sit down and read was a waste of time. He’d say, do something constructive, even if it’s wrong.”

In the years of Eddy’s youth in Oriental, when he’d row that mile over to the opposite shore to catch a bus for the remainder of the trip to school, was where Mary first met him. They rode the school bus together.

“He was an upperclassman,” Mary says. “He was older than me, but always kind and the most gentlemanly, he had his tie on and he was kind to everyone. He was unusual from the word go, he was unusual in his temperament, and he was that way until he died.”

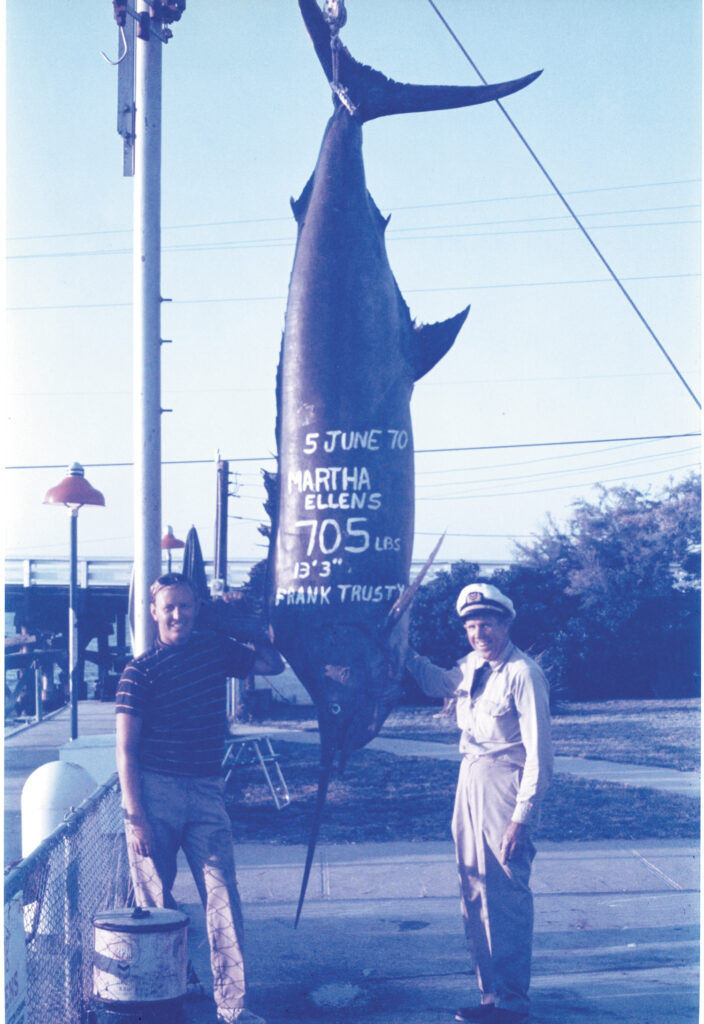

In an interview in 1994, Capt’n Eddy described to a TV reporter about the day Sid Ayotte and Johnnie Willette went out in a private boat and caught the first marlin ever off Wrightsville Beach. Within hours charters were being booked on the Martha Ellen. Then an annual customer named Dr. Childers caught three marlins in one morning. It was reported by Penn Reel Magazine and area charter fishing really took off.

By the time the first marlin tournament was held here in1957, the Hanemans had sold not only the Martha Ellen, but the Martha Ellen Too, and were only fishing their third boat, the Martha Ellens. Capt’n Eddy’s last boat met tragedy that tournament, sinking from an undetermined below-water event. All hands got off safely and Eddy stoically said he felt it was the Lord’s will and that his charter fishing days were over. Mary says he didn’t talk much about that day, they were just enormously thankful that no one was injured.

Pete McKenzie stepped in, inviting Capt’n Eddy to not only finish the tournament on his boat, but continue onto the Big Rock as well. So began Eddy’s career as a private boat captain. He served as the service master at Bradley Creek Marina and looked after the owner’s 65-foot Pacemaker the Lyda G until the marina was sold.

Without a boat of his own to occupy his every waking moment, and now working different hours, he had the time to put into the church work that he loved. He loved flowers and enjoyed working around the property on Hinton. He also spent time working on their nearby rental houses and kept up a few for other people.

Capt’n Eddy now delivered boats up and down the coast, and did short-term captain trips to island places like Bimini and Eleuthera, always bringing Mary some remembrance to share of the new places he’d been.

Throughout his career he would advertise and promote his charter business and he found the time to help W.K. Dorsey promote the ever-growing local tourism industry. He worked tirelessly at selling Wrightsville. At the urging of Dorsey, and going against his normal nature, in the 1950s he even traveled to other areas speaking to groups about the beauty of our area, the fishing and beaches.

In 1994, Captain Eddy Haneman died of a heart attack in his workshop while working on a custom rod.

“If he had to go, I’m so glad it was here at his Peaceful Valley,” Mary says. “I could have lost him so many other ways. Whenever they (fishermen) go out, it was always a possibility.”