Cape Fear River Stripers on the Rise

BY Kemp Burdette

“A very large rockfish weighing 35 lbs was caught a few miles below the city yesterday.” This short statement was published in the Wilmington Star June 18 1869.

A rockfish that big — or striped bass commonly known as a striper — caught in the Cape Fear region would make headlines these days because striped bass populations are struggling to sustain themselves in the Cape Fear River Basin.

Striped bass (Morone saxatilis) were once plentiful in our region especially during the annual spring spawning runs. Stripers are migratory fish or more specifically anadromous fish a term used by fishery biologists. From the Greek roots ana meaning up and dramein meaning to run one can guess that anadromous fish swim or run upstream. Typically anadromous fish spend most of their lives in the open ocean or estuaries and return to freshwater rivers and streams to spawn. The young fish then move back to the open ocean until they reach spawning age and return to the river of their birth to begin the cycle over again.

Stripers aren’t the only anadromous fish the Cape Fear River. Shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon — both federally listed endangered species — American shad and river herring all call the Cape Fear region home though in much lower numbers today than in years past. In fact current anadromous fish stocks in general have declined by about 90 percent and striped bass numbers in the Cape Fear are thought to be only about 10 percent of their population potential.

In their heyday the annual runs of anadromous fish up the Cape Fear River were astounding. The rivers that make up the Cape Fear River Basin — the main stem of the Cape Fear River the Northeast Cape Fear River and the Black River — teemed with anadromous fish and the spring runs were celebrated as a time of abundance for river towns and communities. Accounts from the time describe the runs of fish as endless. In the Cape Fear River stripers would swim well over 100 miles upstream to the fall line the geographical break between the coastal plain and piedmont near Lillington in Harnett County. Here near Smiley’s Falls where conditions were right stripers and other anadromous fish would spawn. These fish were quite literally linking the vast Atlantic Ocean with the upper reaches of the Cape Fear River as far inland as Guilford County.

An old corny joke may be a clue as to what caused the decline of the striper: What did the fish say when he swam into the wall?? Dam!

Today most experts think dams are the leading cause of the decline in stripers and other anadromous fish populations in the Cape Fear River. In the early 1900s the Cape Fear was still a major transportation artery above Wilmington. Barges carried commerce between Wilmington and Fayetteville but navigation wasn’t always easy. The river was unpredictable and seasonal and periodic low water made river depths inconsistent. In response the US Army Corps of Engineers built three locks and low head dams in the early 20th century between Wilmington and Fayetteville to effectively smooth out the shallow spots in the river and facilitate regular barge traffic between the two cities. While the dams were fairly low they contributed to one significant unintended consequence: for the last 100 years they largely blocked the annual spawning runs of anadromous fish in the Cape Fear River.

To be sure dams aren’t the only reason striped bass populations in the Cape Fear are struggling to recover. Water quality and quantity play a huge role in the health of fish populations in the river. There is only so much water in the river and when it is removed for human use it is not available to support aquatic organisms. Water is currently drawn off for drinking agriculture and industry. Those withdrawals will only increase as the state’s population more than one-fifth of which already lives in the Cape Fear Watershed continues to swell. As more and more pressure is placed on shrinking water resources we need to take measures to ensure the river’s ecosystem can sustain itself.

Water quality is also critical to the health of wildlife that lives in and around the river. There are more than 200 permitted wastewater discharges from municipal and industrial users along the Cape Fear. Furthermore the Cape Fear River Basin is home to the highest concentration of industrial animal agricultural operations on the planet and stormwater runoff from these facilities impacts water quality on a daily basis as well. A common problem in the river is low levels of dissolved oxygen in the water column. This is fueled by high levels of nutrients in the water which accelerate algal blooms and reduce the oxygen available to striped bass and other aquatic organisms.

Because anadromous fish by definition spend a significant portion of their life cycle in the ocean their numbers there are impacted as well. In the case of striped bass the impacts are two-fold. First reductions in forage fish populations — the small fish that bigger fish eat — mean the big fish don’t have the food they need to grow and reproduce. A big part of stripers’ diet is shad which has a dramatically reduced population for the same reasons. Striped bass populations are also impacted by unsustainable commercial fishing practices.

“Predators like the striped bass depend on forage fish to survive. The future of our Atlantic coast food web and fishing depends on the abundance of these forage fish “says Joseph Gordon manager US Oceans Northeast The Pew Charitable Trusts.

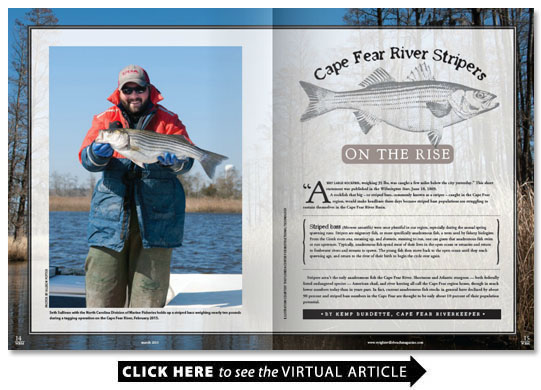

Because it was clear for a number of years that anadromous fish stocks were in serious trouble Joe Facendola fishery technician with the NC Division of Marine Fisheries says “In 2008 state agencies placed a moratorium on striper harvest in the Cape Fear in an effort to reduce pressure on the few remaining fish.” But no one thinks the moratorium alone will bring the striped bass back.

The outlook for striped bass and other anadromous fish in the Cape Fear River Basin is serious but it is far from hopeless. In fact many experts believe the striper can rise again. Steps have already been taken to bring back stripers from the brink and more work is underway and planned for the future.

A fish passage at Lock and Dam No. 1 at Kings Bluff 39 miles above Wilmington in Bladen County just upstream from Riegelwood was constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers and accomplished an enormous step in the process of reviving the local striped bass population. Known as rock arch rapids this series of rock terraces that allows fish to swim over the dam by stair-stepping their way up.

Frank Yelverton former project manager with the Corps of Engineers and current Cape Fear River Watch associate director says the rock arch rapids serve several important functions.

“It maintains a secure drinking water intake just above the dam stabilizes the dam by filling a scour hole that developed downstream and by buttressing the existing structure keeps the lock operational so boats can still move up and down stream and allows fish to navigate over the dam ” Yelverton says.

Fritz Rohde fishery biologist with the National Marine Fisheries Service says another significant step toward the restoration of the anadromous fishery in the Cape Fear River was the formation of the Cape Fear River Partnership. This alliance of key federal state local academic nonprofit and business organizations in the region was formed in 2011 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and has a mission to restore and demonstrate the value of robust productive and self-sustaining stocks of migratory fish in the Cape Fear River.

Dawn York coordinator for the Cape Fear River Partnership says it has developed an action plan that lays out a roadmap to the restoration of the Cape Fear’s anadromous fish.

“A number of action items in the plan are already complete or underway. Cape Fear River Watch in partnership with Dial Cordy and Associates received a grant from the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership and NOAA to enhance spawning habitat for anadromous fish in the section of the river now open to anadromous fish above Lock and Dam No. 1 a project completed in 2014. This project is a first of its kind in the Cape Fear River Basin and we will continue to seek ways to enhance migratory fish spawning habitat ” York says.

Tagging studies funded by Cape Fear River Watch the US Army Corps of Engineers and the NC Division of Marine Fisheries are ongoing and are helping fisheries scientists understand how striped bass and other anadromous fish are moving in the river. Water quality studies funded by Cape Fear River Watch and conducted by University of North Carolina Wilmington scientists are evaluating the area above Lock and Dam No. 1 to determine how algal blooms may impact the spawning success of anadromous fish.

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission also carries out a robust stocking program placing hundreds of thousands of striper fingerlings in the river each year in an effort to maintain a self-sustaining population of stripers. None of these actions alone can save the anadromous fishery in the Cape Fear but when the action plan is implemented as a whole and when fish passage at the remaining two locks and dams is realized the stage will be set for the recovery of the striped bass and other anadromous species in the Cape Fear.

The recovery of the fishery would represent a huge environmental victory for the river’s ecosystem. It would also benefit the marine fisheries that rely on the forage fish that are a critical part of the ocean food chain. But the benefits would be more than just environmental. The regional economy stands to see big gains with a healthy fishery in place. Research from the US Fish and Wildlife Service conservatively estimates an annual benefit of more than $5 million to the regional economy with the restoration of the fishery — and that doesn’t include positive impacts to the marine fishery. Of course recreational benefits would come too as families and friends could once again catch stripers in the Cape Fear like the ones described in the 1869 Wilmington Star.

As fish are swimming over Lock and Dam No. 1 for the first time in more than a century a large group of stakeholders is working to restore striper populations and people are getting behind this endeavor. With continued effort at the national and state level and a groundswell of support from everyday people the striper may well rise again in our lifetime.