Brave Hearts Beat Together

BY K.J. Williams

Bill Ebersbach recruits Purple Heart medal recipients.

The former Marine sergeant asks anyone he sees wearing a veteran’s cap if he or she has a Purple Heart. His recruitment method is similar to the casual exchange that took place in a New Jersey parking lot in 1983 that led to his involvement with the Military Order of the Purple Heart. The medal is awarded for combat injuries or death as the result of enemy action or terrorism. When the veteran responds affirmatively Ebersbach invites him or her to join the Military Order of the Purple Heart Cape Fear Chapter 636.

The order is elite. Only the Medal of Honor the military’s highest honor has fewer recipients than the Purple Heart.

Ebersbach was recognized last year by Purple Heart Magazine for his efforts in growing the membership of the Cape Fear Chapter. He resurrected the defunct chapter in 2005 bringing eight former members back into the fold. He then recruited 64 more members.

The military order is a brotherhood Ebersbach says.

“The one thing that binds us together is that little piece of gold and purple stone ” he says.

The Purple Heart medal has an image of George Washington on its heart-shaped face set in a golden bronze. The medal was first created in 1782 on Washington’s orders to honor wounds received during combat action and meritorious performance of duty states the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Ignored for almost 150 years it was reintroduced as an award on February 22 1932. Since then an estimated 1.8 million Purple Hearts have been awarded states the National Purple Heart Hall of Honor in New York. An exact figure is nearly impossible to calculate as most early Purple Hearts were not recorded and many were lost when the National Personnel Records Center caught fire in 1973.

August 7 is recognized nationally as Purple Heart Day.

This is a time to remember the sacrifices of those who were wounded or killed in combat. The Cape Fear region will recognize Purple Heart recipients during the Second Annual Cape Fear Purple Heart Dinner on August 2 at the Wilmington Convention Center.

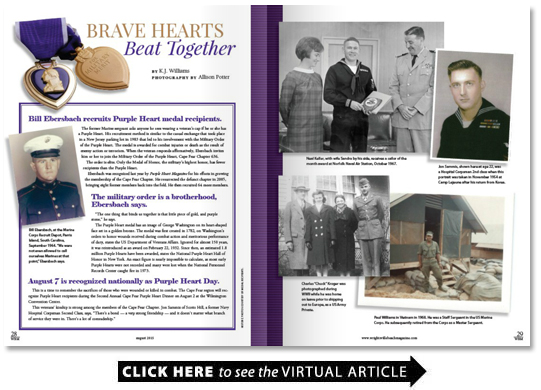

This veterans’ kinship is strong among the members of the Cape Fear Chapter. Jon Sammis of Scotts Hill a former Navy Hospital Corpsman Second Class says “There’s a bond — a very strong friendship — and it doesn’t matter what branch of service they were in. There’s a lot of comradeship.”

Retired Master Sergeant Paul Williams

Retired Master Sgt. Paul Williams spent 26 years in the Marines hearing the battle cry that also conveys enthusiasm: Oorah!

But the 77-year-old hasn’t stopped fighting with his retirement responding to his own internal cry to battle working to help get benefits for other veterans.

“I like to make sure that each veteran that rates benefits gets benefits ” he says.

Williams has lived for the past 40 years in Porters Neck with his wife of 57 years Doris. He enlisted in 1956 serving in the Vietnam War. He retired in 1982.

He received his Purple Heart while serving with the Kilo Co. 3rd Battalion 9th Marine Regiment in Vietnam. The 1st Battalion had been almost annihilated in a marketplace when his battalion arrived he says.

“We were walking down this pathway and all of a sudden the enemy just cut loose on us ” he recalls. “They ambushed us and I got hit.”

He was wounded by shrapnel and bandaged by a Hospital Corpsman.

“You can tell when it has hit you because it’s hot and it burns your flesh ” Williams says.

He got up and kept going despite the burning no painkillers in sight.

“It heals itself up ” he says. “When you’re in combat you have to improvise. ? I was too busy trying to save my life.”

Today the Virginia native says he respects the Purple Heart he received for what it represents.

“Anyone who gets one — I take my hat off to them — because they deserve it. They put their life on the line for their country. They gave part of their body for their country. I admire anyone who does that ” he says.

Raised in Amherst County Virginia Williams traveled the world with his family while in the Marines. Williams served during pivotal historic events including the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in 1961 and the Tet Offensive in Vietnam — the 1968 counterattack that held off the enemy while also inflicting heavy casualties marking a turning point in the war.

After his military retirement Williams worked as a health inspector at the Brunswick Nuclear Plant outside Southport for 12 years retiring in 2000.

He still occasionally has flashbacks to his days in Vietnam a holdover of his post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It’s an instantaneous combustion that just goes off in your head ” he says of a recent episode that occurred during a church service leaving him quiet upset by the drumming sound that reminded him of explosions.

Williams receives disability compensation from the military. He attributes some of his health problems including prostate cancer — currently in remission — to his exposure to Agent Orange an herbicide used to kill foliage in Vietnam. Diagnosed with diabetes his right leg below the knee had to be amputated.

Williams says it is important to lend support to veterans whether or not they’ve received the Purple Heart.

“They think a lot of people don’t care about them because they don’t know where to go or who to talk to ” Williams says. “They’re looking for answers to problems they’re having. We can solve each other’s problems if we just hang in there.”

Retired Army Communications Sergeant Charles “Chuck” Kroger

Charles “Chuck” Kroger 91 of Wilmington knows he is one of the few Army veterans of World War II still living. He served as a communications sergeant and received his Purple Heart after both legs were broken by enemy fire as he repaired wire lines used to maintain communications between platoons on a French battlefield. Kroger was assigned to the 84th Infantry Division which was preparing to cross a tributary to the Lower Rhine section of the Rhine River which the Germans had flooded as a deterrent.

“The artillery came while we were in the town waiting to cross the river ” he recalled. When the shout went out to get down because of artillery fire Kroger who was wearing headphones while he worked on the communications lines didn’t hear it.

“I was standing up and it took out both legs ” he says. “The (mortar) shell landed right next to me.”

He was evacuated to England on a hospital ship and was operated on twice for breaks in both legs. While in an English hospital he was visited by a general who gave him his Purple Heart medal.

“The general came in and said ‘Kroger — I wish I was pinning this on a uniform not pajamas ‘” he says.

After his military service the native New Yorker returned to college at the University of Connecticut in Storrs Connecticut graduating in the 1950s before beginning his career with the Central Intelligence Agency.

Kroger credits his military service with his future career path.

“It dawned on me that there was an activity that I could contribute to and I thought it was important ” he says of his career in public service.

After retiring in 1977 he moved to Wilmington. Kroger was a widower with an adult son when he married his wife Betty a Wilmington native in 1981.

Kroger’s bravery was further acknowledged when six years ago he was belatedly awarded a Bronze Star medal for his actions in 1945. His inquiry into another matter may have prompted a re-examination of his military record but Kroger isn’t sure why the delay occurred possibly due to lost paperwork but he said he was surprised and grateful at the long overdue recognition.

The fellowship he finds in the Military Order of the Purple Heart Cape Fear Chapter 636 serves to keep his ties to his military past alive and gives him membership to a group that shares some similar memories.

“Unless you’ve been there you don’t understand a lot ” he says.

Retired Navy Hospital Corpsman First Class Neal Keller

Neal Keller’s two Purple Hearts were awarded in quick succession for his 1967 combat injuries sustained less than one month apart during the Vietnam War.

The 75-year-old resident of Hampstead was a Navy Hospital Corpsman 1st Class who stood beside Marines on the battlefield armed with a pistol for self-protection and medical supplies for treating the wounded. The South Carolina native served with the 1st Battalion 4th Regiment 3rd Division and his medals include the Silver Star.

As a Hospital Corpsman Keller said he provided minor medical care in the field.

“You treated them — whatever the injury was — then you got them evacuated ” he says.

Keller doesn’t recall everything about the March 22 1967 shrapnel wound to his cheek but he believes he probably slapped a butterfly bandage on himself and continued treating the injured.

On the day he was injured his unit had run into an entrenched Vietnamese unit and a major battle ensued.

“During the course of that we were taking a lot of casualties in a situation where every time we tried to fly somebody out [for treatment] we would take more casualties ” he recalls. “And two platoons had gone forward and a firefight started and I moved up to assist corpsmen up there.”

Keller adds he wasn’t even immediately aware of his injury amid the constant sound of cracking rifles and mortar fire.

“We were getting a lot of mortar fire and small-arms fire when I got wounded ” he says. “I had everybody’s blood on me so mine wasn’t noticeable.”

Keller remembers his captain asking if he was wounded and responding in the affirmative before he re-entered the fray.

“You’re focused on who you have to take care of and what you have to do to get there ” he says.

Sixteen days later on April 7 1967 Keller was more seriously wounded. He was alongside Marines conducting a sweep to locate the source of the rounds being fired at US aircraft outside of the US combat base at Dong Ha.

Keller felt an explosion behind and underneath him. He sustained shrapnel injuries to his legs and back resulting in damage to his left kidney and the removal of his spleen. A piece of shrapnel still remains lodged in his abdomen.

“Something blew up right behind me and underneath me ” he says.

He was evacuated by helicopter and operated on at a battalion aid station a type of front-line field hospital. The operations were successful despite the bare-bones accommodations including walls constructed of green-painted packing crates.

His next stop was an actual hospital at Da Nang a Vietnam-era military base and then he was sent to the US military base at Yokosuka Japan. A day later on his birthday he was shipped back to the United States.

He acknowledges the lasting impact of his injuries.

“I’ve got scars — I’ve got parts missing ” he says; residual twinges of pain he calls little odds and ends he says haven’t hindered him at all.

He served in the Marines for seven and one-half years. He then finished his college education at Old Dominion University in Norfolk Virginia. After graduation he managed hospital laboratories in North Carolina and then Florida. After retirement Keller and his wife Sandra moved back to North Carolina. They’ve lived in Hampstead for about four years. The couple has a son and daughter and four grandchildren. He says the richness of the life he lives still hasn’t erased his combat memories however.

“I think about the guys — the situations ” he says.

Retired Naval Hospital Corpsman Second Class Jon Sammis

The Chinese sniper who fired a bazooka at Jon Sammis during the Korean War in 1952 fortuitously provided important military intelligence hidden within the shell’s fragments. The Russian lettering inside offered proof the rockets were supplied to China from Russia not American-made rockets that had been captured as suspected.

Sammis a Navy Hospital Corpsman Second Class assigned to providing basic medical care to wounded Marines sustained injuries to his right arm and leg but retained the presence of mind to notify his commanding officer of the important clue in the rocket fragments.

To maintain lines he couldn’t be evacuated until darkness fell. Because he was the only Hospital Corpsman there Sammis says he had to instruct a Marine to administer morphine to him.

Sammis says he wasn’t worried about his welfare while he lay wounded.

“It just happens to be one of the things that Marines do. They protect fiercely any corpsman that’s with them because they rely on these guys for their own [medical] protection ” he says.

When he was evacuated he was briefly treated at an aid station then went by rail to reach the docked hospital ship the USS Consolation for surgery. While he was recuperating from surgery the ship’s commanding officer presented him with the Purple Heart for combat wounds sustained when he was conducting observations at an outpost ahead of the front lines. He also received the Bronze Star medal with the combat “V” for his service in Korea with the Fox Co. 2nd Battalion 5th Marine Regiment.

Today he still has some residual numbness and muscle weakness in his right leg because of his injuries.

After he recovered Sammis was sent to work at a regimental aid station located three miles behind the front lines. The job of Hospital Corpsman fit Sammis’ natural aptitude for science but it wasn’t the job he wanted when he enlisted.

“I wanted to be a cook ” he says with amusement. Navy officials however decided the New York native had potential in medicine. “So they decided I would do better as a corpsman than as a baker ” he says.

After military service Sammis attended college on the GI Bill at C. W. Post College of LIU a college in the Long Island University system graduating with a bachelor’s degree in biology. He then taught school in Syosset New York on Long Island from 1959 until 1987.

His military training was serendipitous leading him to his career as a science teacher and foreshadowing his second career.

During the summers Sammis revisited his medical military roots working as an orderly in a civilian hospital.

As he prepared to retire from teaching Sammis studied nursing at Farmingdale State University in New York. He worked as a registered nurse for five years. He and his wife Barbara moved to Scotts Hill in 1993. They have two children three grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Retired Marine Sergeant Bill Ebersbach

Bill Ebersbach wears his military service on his right hand. As a result he extends his left hand to shake when he meets someone. He was awarded three Purple Hearts for Vietnam War combat injuries including an absence of sensation in his right hand.

A New Jersey native Ebersbach enlisted in 1964 when he was 17 years old. He turned 18 at Parris Island during his Marine Corps basic training in South Carolina.

Ebersbach 68 spent nearly four years in the Vietnam War on two tours of duty during his 10-year Marine Corps career.

While serving as a rifleman with the 3rd Battalion 4th Regiment during Operation Hastings — which successfully pushed the North Vietnamese back across the demilitarized zone (DMZ) — Ebersbach sustained a shrapnel wound to his hand. He was evacuated and then treated at the military hospital at Da Nang. In 1967 again in the DMZ he took shrapnel in his back.

In 1971 Ebersbach was an air traffic controller assigned to the Marine Air Traffic Control Unit No. 6 but he would volunteer to fly with gunners as another gunner firing weapons on his day off. He was shot in the leg while he rode inside a helicopter that was under fire earning him his third Purple Heart. He was once again sent to the military hospital at Da Nang for treatment of his leg before returning to duty.

He sometimes struggles to recall the details of what he purposely tries to forget.

“These are things I don’t think about ” he observes.

After his service he continued to be plagued by nightmares and other symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder an anxiety disorder for which he has been receiving ongoing treatment for ten years. At times he continues to have pressure and tingling sensation in his right leg.

Ebersbach is philosophical.

“I’m not a victim ” he says. “I’m proud of what I did. And if this is the consequence of it then so be it. I’m not going to cry about it. And there are a lot of guys who are in a lot worse shape than I am.”

Following Vietnam Ebersbach served six more years and then put his military training as an air traffic controller to use in the civilian sector working for the Federal Aviation Administration for 30 years.

He worked in four cities before moving to North Carolina with his wife Karen. The couple has lived in Wilmington since 2004.

Today as Commander of the Military Order of the Purple Heart Cape Fear Chapter 636 Ebersbach devotes himself to seeking assistance and recognition for veterans as do the other members of the order.

He’s adamant that no other veteran experience the disrespect that many Vietnam veterans faced when they returned stateside after serving in an unpopular war heavily protested in the United States.

“This country will never again treat a veteran — especially a combat veteran — the way they treated the Vietnam vet ” he says. “The guys and also some of the women who went over there they were all treated in the same way and that was with disdain and disgust.”

He honors his military connection in his home where he has a display case that contains his medals. Also on display is the Purple Heart of his late father William Ebersbach who served with the Marines in World War II; and a medal that belonged to his maternal grandfather who received the equivalent of a Purple Heart the Combat Wound Certificate and a Silver Star for his Army service in World War I.

Purple Hearts stockpiled During WWII

Current Purple Heart Stats

500 000 Purple Hearts were made before Operation Downfall in anticipation of casualties during the Allied Invasion of Japan but the medals were never awarded because Japan surrendered before the operation.

1.5 million Purple Hearts were made for WWII only 495 000 were given out during the war.

150 000 Purple Hearts from WWII remained with the Armed Services to be given out as of 2003.