Beach Bites

BY Jonathan Hartmann Emmy Errante and Henry Liverman

Fish Out of Water

Off the Hook

By Jonathan Hartmann

Mark Batson has one. John McClatchey s Fish House has one. Taylor Miller winner of the Big Rock Blue Marlin tournament has one. Schools of stainless steel and copper fish made in a Wilmington North Carolina warehouse decorate homes and landmarks like trophies.

On the surface the R Mended Metals warehouse looks less like a holding tank for colossal aquatic sculptures and more like a storage unit for boats and fishing equipment. Inside seahorses seemingly swim above a sea floor covered with sheets of metal waiting for the touch of Roy Taylor his wife Rebecca and their crew.

The Taylors didn t always make a living creating custom aquatic sculptures. Roy worked in the scuba industry for almost twenty years.

I have a BS in marine biology from UNCW he says. I learned to scuba dive and I got my captain s license.

Taylor and his business partner had two boats accommodating 30 divers at a time.

It wasn t a big jump to come in here to learn to do another 50 things Taylor says.

After selling his half of the scuba shop he learned to weld while fabricating a sand rail dune buggy before venturing into the world of art and interior design.

He s basically a self-taught welder Rebecca Taylor says.

People use that term very liberally Roy Taylor says. I didn t learn every single thing that I know from picking it out of my brain. I read and I talked to people and I learned from people and they learned from me. But I guess as far as anybody else goes I m as self taught as they come.

The original owner of the R Mended Metals warehouse also a friend asked Taylor to make a sea turtle followed by a seahorse.

The complicated plasma-cutting program was a trial and error process.

By the time I finished the seahorse I could draw at will in the program Taylor says.

After the designs are digitized R Mended artisans select a template from Taylor s program and set the dimensions for the final result before the shape is put on the plasma table that cuts through sheets of steel and copper at more than 2 700 degrees Fahrenheit. During the finishing process cut metal is wet sanded for hours buffed and sand blasted for a smooth finish. One sculpture may hold more than four textures.

Near the end of the process the stone bit — a type of stylus — is used to color in the sculpture s fine lines. Lastly driftwood is selected specifically for the delicate mounting process.

The cool thing is that people come in with their own ideas and we get to be involved in the creative process and see it from start to fruition Rebecca Taylor says. That part is very rewarding and it keeps our skills on point and keeps everything interesting.

It s a dream job for everyone involved in the process and it takes the effort of the entire staff to create the shimmering trophies before they re ready to be sent out into the world.

You come in and it s not the same job every day says Jon Lewis an R Mended artisan. Being able to change pace you don t have to be stuck on one thing very long. We enjoy what we do and take pride in it. We re tired at the end of the day for sure.

Buckets of Fun

The Scoop On Sandcastles

Story and photography by Emmy Errante

Sandcastles don t necessarily have to take the shape of castles. The right type of sand can be molded into just about anything.

A walk down Wrightsville Beach on a summer afternoon reveals the occasional sea creature sculpture evidence of children and their imaginations.

Sea Creature Sculptures

Type of Sand: Damp

Tools: Shovels shells sea oats

Just south of Johnnie Mercer s Pier five children put the finishing touches on a sand sculpture masterpiece. They create two whales a shark a sea turtle a starfish and an octopus.

[It started as] a whale-building contest 11-year-old Madysen Edgington says. You use the sand that you get when you dig down.

Nearby 8-year-old Gavin Edgington and 13-year-old Liv Scharfe gather pieces of dried sea oats that have blown from the dunes to create the whale s baleen and water spout.

Use your surroundings Scharfe says. You can use other stuff besides sand.

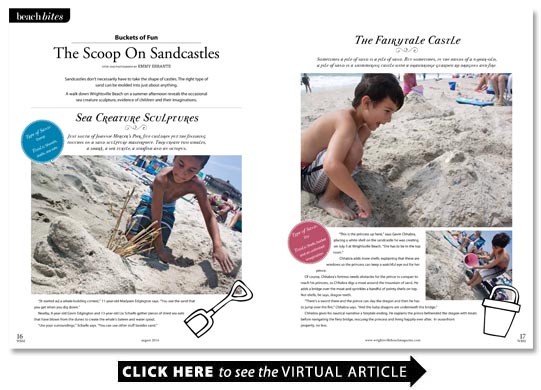

The Fairytale Castle

Type of Sand: Dry

Tools: Shells bucket and an unlimited imagination

Sometimes a pile of sand is a pile of sand. But sometimes in the hands of a 6-year-old a pile of sand is a shimmering castle with a drawbridge guarded by dragons and fire.

This is the princess up here says Gavin Chhabra placing a white shell on the sandcastle he was creating on July 5 at Wrightsville Beach. She has to be in the top room.

Chhabra adds more shells explaining that these are windows so the princess can keep a watchful eye out for her prince.

Of course Chhabra s fortress needs obstacles for the prince to conquer to reach his princess so Chhabra digs a moat around the mountain of sand. He adds a bridge over the moat and sprinkles a handful of pointy shells on top. Not shells he says dragon teeth.

There s a sword there and the prince can slay the dragon and then he has to jump over the fire Chhabra says. And the baby dragons are underneath the bridge.

Chhabra gives his nautical narrative a fairytale ending. He explains the prince befriended the dragon with treats before navigating the fiery bridge rescuing the princess and living happily ever after. In oceanfront property no less.

The Dripping Fortress

Type of Sand: Very wet

Tools: Hands and shovel

The most intricate sand sculptures known as drip castles must be built in the wet sand near the water s edge. For that reason these aren t the easiest castles to create when the tide is rising although 11-year-old Emerson Holibaugh is determined to try.

You should build a wall to try to save your castle Holibaugh says reinforcing his castle with extra sand as the waves lap up against the sides.

He also carves out a moat between his castle and the ocean to catch the incoming water. He grabs handfuls of watery sand from inside the moat creating turrets out of the dripping sand.

You have to let the wet sand drip through your fingers he explains.

Ancient Alien

Nature’s Nostradamus

By Henry Liverman

The ghost crab once called a secretive alien from the ancient depths of the sea by the American Natural History Museum Journal in 1940 is now found worldwide. But of the roughly 20 different species only one the Atlantic ghost crab is found on the US East Coast says local coastal ecologist Andy Wood.

Part of the ghost crab s mystique is its nocturnal nature it only hurries seaward at night to moisten its breathing gills. The crab spends most of its time underground in a shallow burrow it calls home. There it stays cool through the hottest hours of the day and coldest months of the winter.

Though a cousin to the fiddler crab the ghost crab is a much more solitary crustacean. When encountering an unfamiliar visitor in its burrow the crab displays its claws for intimidation Wood says and rubs the claws striated ridges together displaying its intent to be left to its hermetic ways.

Though mysterious and entertaining ghost crabs serve an important purpose in the local ecosystem. They have few natural predators or competition for sustenance in their food chain. This paired with a flexible diet Wood says is what makes them top predators in their environment.

The generalist diet and their specific adaptation to living in and around a very dynamic open beach environment — by burrowing — are the big keys to their success Wood says.

The ghost crab is also important as an indicator species. In its food chain the ghost crab can prey on almost anything it wants. So if something is wrong with any of the chain s links it shows in the ghost crab. This means the health and stability of the ghost crab population closely reflects the state of the beach ecosystem as a whole.

Their absence may tell us that something has happened to the sand — or that their food is not there. If those are absent the ghost crab is going to be absent Wood stresses. They are an indicator species but what they indicate is a need for more study to figure out why the crab is not there.

As undeveloped beachfront property declines there are threats to the ghost crab s habitat. The crab s biggest threat is beach nourishment efforts. Pumping new sand onto the inter-tidal zones fills burrows and kills crabs pulled into the dredge pipes says Nancy Fahey volunteer coordinator for the Wrightsville Beach Sea Turtle Project.

Fahey says the introduction of this new sand brings toxins not naturally found on the beach harming not just ghost crabs but the habitat of every creature that is a part of the coastal ecosystem.

Unless you understand a lot about the ecosystem you wouldn t look at it [as hurting the crabs]. We may not realize at first glance what an impact it has; but it does it definitely does Fahey says of the renourishment process.

Ghost crabs are an active threat to animals such as sea turtles as the chief cause of turtle egg and hatchling mortality. Sea turtle protection efforts in particular take specific measures to deter crabs from turtle nests and from hatchlings on their march toward the sea.

We just try to live with the ghost crabs Fahey says. We don t like for them to get the turtles but we know that it happens. We try to get them out of the way as humanely as possible. I m a big believer that all things in an ecosystem serve a purpose.