A Redemption Story

BY Simon Gonzalez

Dale Varnam insists he is not crazy. He makes that abundantly clear up front. And in the middle. And at the end.

“I don’t want you to think I’m crazy” is a repeated phrase during a typically long visit with the proprietor of Fort Apache the quirky roadside attraction/museum/junk store near Supply in Brunswick County.

There are variations on the theme. “Everybody thinks I’m crazy.” “I’m not crazy.” “You’re going to think I’m crazy.” “Do not think in any way that I’m crazy.”

Each phrase enunciated with a Brunswick County drawl that out-of-state visitors find endearing is said with an ever-present mischievous twinkle usually accompanied by a chuckle from the pleasantly smiling man with the white beard and hair.

The emphasis on his mental state is understandable. The big bus filled with zombies parked near the commodes with legs sticking out the top is the first oversized clue that this place is a little strange and bizarre.

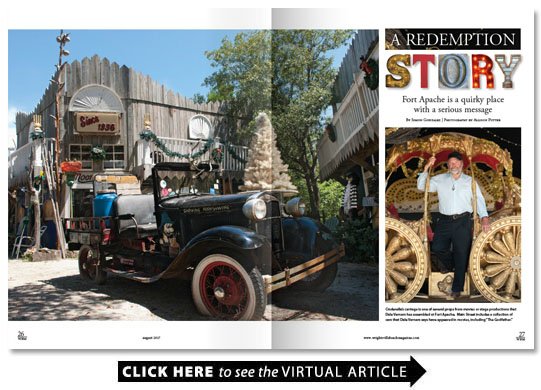

After parking near the bus visitors can go through the gates and walk through a whimsical surreal “town” that includes antique cars and a replica Love Bug haphazardly parked on the main street Cinderella’s gold carriage parachuting CIA agents caught in a tree mannequins and movie props inside a collection of themed buildings and a menagerie of chickens turkeys ducks and Dale’s dozen or so cats.

Or they can go inside the store crammed virtually to the rafters with an eclectic assortment of used merchandise. Some might call it junk but then again one man’s junk is another man’s treasure — so says a saying on a T-shirt sold in the store.

“The average person would see it as just a junk hole. I see it as you’re going to dig through that next box or you go around that next corner and you’re going to find that thing you’ve always been looking for ” says Daniel Shelton a visitor from Rockingham County.

The building includes the “tunnel of treasure ” a long arched offshoot jam-packed so full of things there’s barely room to get through.

In a portion of the tunnel that’s become one-way because of the encroaching treasure Dale runs into Daniel and his wife Abby who is doing her best to push 8-month-old Grayson in a stroller down the narrowing pathway.

“It’s a mess through there ” Daniel says. “You need to get some of that cleaned up.”

Dale doesn’t take offense. He and Daniel became good friends a couple of years ago when the young man first visited Fort Apache.

“I was scared to stop the first time I came by ” Daniel says. “I thought I was going to get shot. But I told my girlfriend — she was my girlfriend then but we’re married now — I said ‘You know what? I’m going to take a chance and I’m going to stop. I’m going to take some photos.’ And then he comes out. We hit it off from there.”

Just about everyone who stops by hits it off with Dale. After a few minutes they’ve likely made a life-long friend.

Jim Danko a visitor from Leetonia Ohio just met Dale two hours ago but when he leaves the two men hug and call each other brother.

Jim and his family came down on vacation. On the way to the beach one day they happened past Fort Apache.

“We drove by and I spotted the panel van ” Jim says. “I like old cars. I told my wife before we leave I’m going to go down there and find out what’s going on.”

The panel van is parked by the zombie bus the first thing travelers see coming around the curve heading south on Stone Chimney Road toward Holden Beach. Like most things at Fort Apache it’s not an ordinary panel van. It’s the SWAT van — Sexy Women’s Assault Team serving Brunswick and surrounding counties.

That doesn’t matter to Jim. It’s still an older car one of many on the grounds. He sees them all during his personal tour with Dale.

“It’s fantastic ” Jim says. “That’s the only word I can say. I like the cars the people are nice it’s amazing.”

Dale finds out Jim is from Ohio and tells him that he graduated in the top 10 of his class from OSMI. Jim looked puzzled.

“I said ‘You don’t know where OSMI is?'” Dale says. “That’s Ohio State Mental Institution. I got him good! He’ll never forget me now.”

You laugh a lot when you’re around Dale. His zany sense of humor is his way of making an impression.

“Sometimes when I first see somebody — you’re going to think I’m crazy — I’ll be there talking and I’ll say ‘Hold still a minute ‘” he says. “I reach into my pocket and I pull out an arrowhead. I’ll pick their nose and say ‘Down here in the South we call them boogers.’ It’s the first impression. They think I’m crazy but they’ll never forget me. Is that crazy?”

Well maybe just a little. In truth he doesn’t really mind if you suspect he’s a little off. After all “Home of Crazy Dale” is emblazoned on the side of one of his vehicles — the blue van with the hobbyhorse head inside.

But if there is madness there is also method. Fort Apache exists as a platform for Dale’s redemption story.

“I thank God I’m here ” he says. “That’s why I do all this crazy stuff; it just draws people. Most of them come by and say ‘What’s going on?’ It opens so many doors for me where I can tell people you don’t want to go in life where I’ve been. You know what I mean? It gets me to where I can help people and it makes a difference.”

Dale’s family has owned the land here for decades. He still runs the junkyard his daddy opened in 1957. But the roadside attraction traces its origins to the 1970s when Dale began “dancing with the devil.”

Varnams have been fishing the waters off North Carolina for about 150 years. It can be a hard life. Dale started out as a fisherman but figured out how to use his boat to make money — a lot of money — without depending on the uncertain economics of the seasonal catch. He began smuggling cocaine up and down the East Coast.

“Greed’s what got me in all of the problems I had ” he says. “The greed of money. I never did drugs myself but greed of money’s a worse addiction than drugs.”

He was arrested in 1988. He pleaded guilty to 36 drug trafficking charges but cut a deal. He informed on 150 drug suspects and escaped with a suspended sentence and probation.

“I walked out of that courthouse with a big bull’s-eye on my back ” he says. “It’s a wonder I wasn’t shot or killed took 100 miles offshore and thrown overboard you know what I’m saying? Things like that happened.”

He moved back to Brunswick County and gave up the drug-smuggling business. But he admits he was still doing dumb stuff.

“My nephews and them had a burglary ring in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County ” he says. “They were stealing stuff up there and putting it in pawn shops down here and stealing stuff down here and taking it back up there. One night I got a knock on my door. It was them. They sold me a refrigerator a couch and a chair. I didn’t pay but $300 and it was still in the box. Like an idiot I wasn’t thinking. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t know it was hot when I bought it.”

It wasn’t long before he got another knock on the door.

“Here came 16 agents busting in the house ” he says. “The first thing they did was one of them came and sat on the couch one sat in the chair and one of them leaned on the refrigerator.”

Dale says he was set up ratted out by either the nephews or someone from the old days. News reports at the time said investigations determined he was the head of the theft ring and agents seized five truckloads of stolen goods from his property.

Either way he was in trouble with the law again. This time there was no way out. He pleaded guilty to 12 felony charges and in June 1992 was sentenced to 35 years in jail.

“After all them years I ended up in prison ” he says.

Dale was born in Brunswick County on Dec. 30 1951 and grew up in church. But if he heard the Bible verse that says the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil it didn’t take.

“I got saved and baptized and everything ” he says. “That was March 16 1972. The pastors from all the different churches come together to baptize us all down at Brown’s Landing. From that moment on in my life it was like in some areas I started dancing with that devil. I would sit in church and look at my watch and couldn’t wait to get out to go unload [drugs from] a boat or a plane or something.”

Sitting in a jail cell in Central Prison in Raleigh gives a person a lot of time to think and reflect. Dale realized he had done a lot of bad things. Looking for redemption he tried to reconnect with the faith he had forsaken.

“I needed some prayer but I had nobody to pray for me ” he says. “So really I had to go in the closet with that Man upstairs. I would lie on my bunk and pray in that closet. And then when I came back out and came back home there had been so much change in the world. So I’m still in that closet with the Man upstairs.”

His prayers turned into a conviction that he needed to use his experiences as a cautionary tale to keep others from making his mistakes and to tell his story to as many people as possible.

He was released from prison after serving 10� years of the 35-year sentence. He started building Fort Apache to get people to stop so he could talk to them.

Most of the things in the town came from movies and plays Dale says donated by production companies or sent by “friends in the business.”

“A lot of it is donated from the theatrical world ” he says. “And a lot of it is what studios and stuff would throw away.”

He points them out on a tour of the grounds. Cars from “The Godfather” and “The Green Mile.” The casket Eddie Munster slept in on “The Munsters.” The safe from “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” A barber chair from Sweeney Todd. Props from theatrical productions of “Seussical ” “Cinderella” and “The Wizard of Oz.” The Bailey Building and Loan sign from “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

In the thrift shop there’s ET.

“Look at what I just got in ” Dale says. “I got him last week from Pittsburgh. This is the real ET.”

While those things are attention-getters Dale wants the real attraction to be the anti-drug message. The zombie bus out front is the “Crack Head Express ” with a big sign leaning against it urging everyone to “stay off the rock.” The theme is repeated throughout Fort Apache.

Just to make sure the message gets across Dale tries to meet everyone who comes by.

“A lady come here yesterday she had drove all the way from the other side of Charlotte ” he says. “She had just spent $62 000 on her daughter who had come out of rehab. I told her to go in that closet. I said ‘You go home you get in that closet with that Man.’ I said ‘You don’t have to talk out loud. Whether it’s in your car or your bathroom your bedroom get down on your knees and talk to Him. He’ll hear you and you’ll be surprised.'”

Dale does more than talk to people. Fort Apache is open most days during the summer. But you won’t find Dale there on Tuesday mornings. That’s when he makes the rounds of area thrift stores collecting donations that end up in his own store. Or in the big trailer out back in the junkyard.

“We go and pick up and they donate to us ” he says. “We’ve got Boiling Springs Southport and Leland that we have to hit on Tuesdays. All them keeps us going.”

The stores are willing to donate because Dale doesn’t keep the money at least not any more than he needs to keep the place open. Some of the proceeds go to area ministries. He fills the trailers with bags of clothes donating them to a nonprofit that takes them to Haiti.

“They need them over there more than we do here ” he says.

The generosity is one of the reasons Daniel Shelton stops by whenever he’s in town.

“Words can’t describe him ” Daniel says. “Just thinking about how his life’s been it kind of brings a tear to your eye. It’s just touching. He’s shared a lot with me. He’d do anything. He’d give you the shirt off his back. I know he would. I’ve got faith in him. He’d help anybody. You don’t meet many people like that at least not in these days.”

It’s all part of the new Dale the one who rejected the greedy Dale.

“I try to help people now ” Dale says. “We can’t take nothin’ with us when we leave here.”