A Fleet for Liberty

Wilmington’s North Carolina Shipbuilding Company helped the United States win a war

BY Simon Gonzalez

Originally published in the October 2017 issue of Wrightsville Beach Magazine.

Head to the west end of Shipyard Boulevard, get as close as possible to the shadow of the big blue cranes, and it just might be possible to hear the echoes of the past.

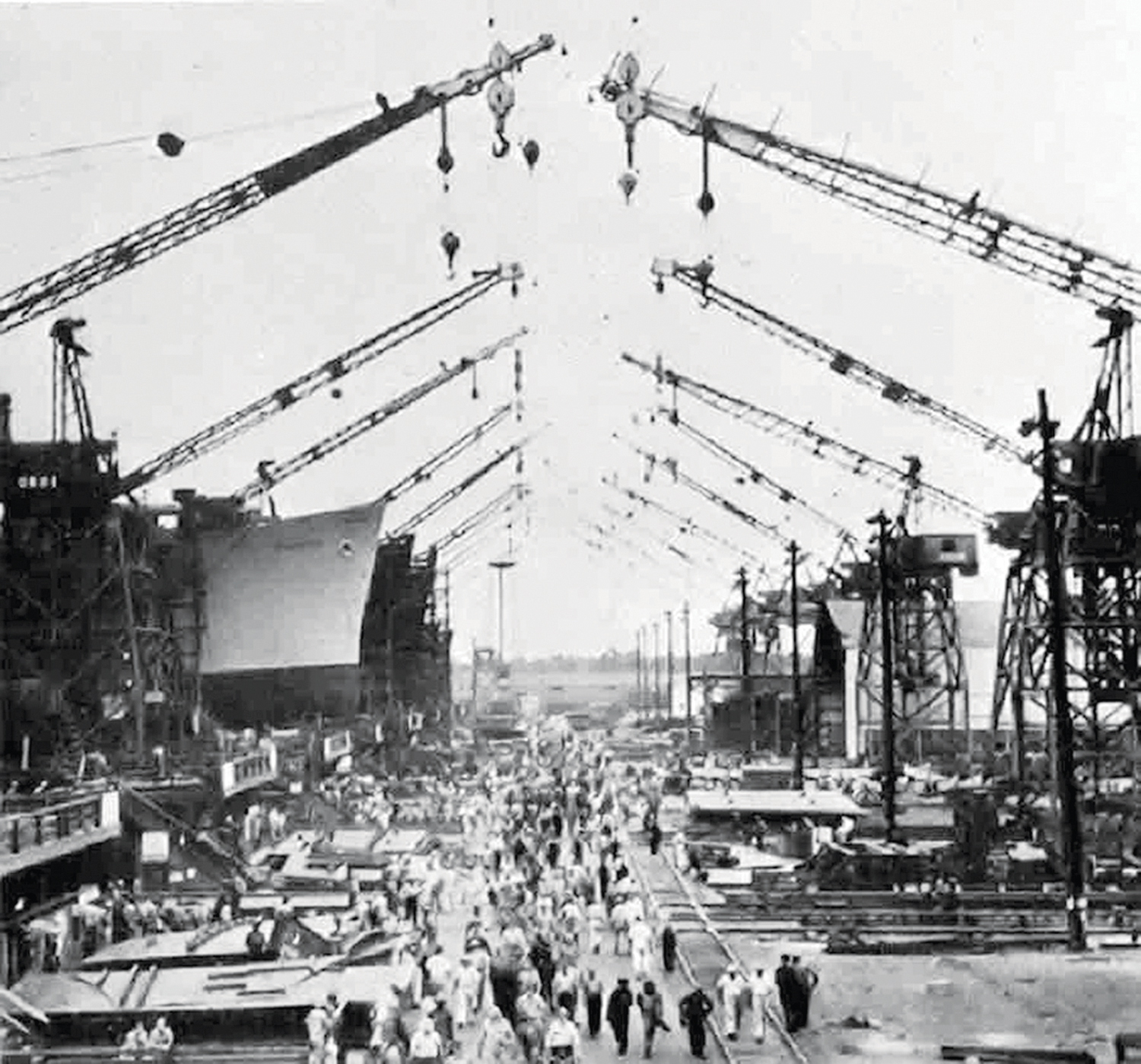

This once was the location of the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company (NCSC). From 1941 to 1946, tens of thousands of men and women swarmed through the gates to build the famous Liberty ships and other vessels that helped the United States triumph in World War II.

The shipyard closed in October 1946. But with a smidgen of imagination, it’s possible to picture the once-thriving company that established Wilmington as a commercial and economic hub.

“Believe it or not, a number of structures are still in use,” says Wilbur Jones, World War II historian and author.

There’s the building that housed the mold loft, once a repository of men, equipment and steel and where hulls for the Liberty ships and later the C-2 class vessels were prefabricated. A handful of other buildings are intact, as are the railroad tracks that brought in the raw materials that became big ships.

“You don’t have to close both eyes,” Jones says. “You can picture it.”

The problem with picturing it is finding it. The remnants of the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company are behind guarded gates. The property is now the Port of Wilmington. Because of security concerns, the public can’t enter at will.

“Nobody can get in the shipyard,” Jones says. “It’s been that way for years.”

Jones occasionally takes groups into the facility and points out the old buildings, but there are no plaques or memorials. There isn’t a museum or even an exhibit in town dedicated to the NCSC.

The Wilmington area is replete with history. Fort Fisher. Antebellum mansions. The railroad museum. The Battleship North Carolina. But nothing had a greater impact than the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company.

“There were two significant events that happened in Wilmington in the course of its history,” Jones says. “One was the fall of Fort Fisher, the last Confederate port, and the capture of Wilmington in 1865 by the Union army. The other was the opening of the shipyard and the boom of World War II.”

Preparing for War

It was the winter of 1940. The United States had not entered the con- flict that was threatening to engulf the world, but President Franklin Roosevelt wanted to help the nations fighting Germany and Italy.

“They were trying to keep the British supplied with munitions and food,” says Ralph Scott, a history professor at East Carolina University and author of The Wilmington Shipyard: Welding a Fleet for Victory in World War II.

Roosevelt proposed a “bridge of ships” that would ferry desperately needed supplies across the Atlantic. He called for new shipyards that would build a massive merchant fleet. While ostensibly an effort to help Great Britain, the president was looking ahead to the day when the United States would be drawn into the war.

“Everyone thought it was inevitable, and so did President Roosevelt,” Jones says.

The U.S. Maritime Commission awarded a contract to the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company of Virginia, which agreed to build a shipyard in Wilmington “adequate to deliver 25 Libertys by March 15, 1943.”

The company selected and purchased a 59.6-acre location about three miles south of downtown Wilmington, on the east bank of the Cape Fear River.

Five Years of North Carolina Shipbuilding 1941-1946, a book published by the company, described the site as ideal, “with the physical properties of deep fresh water, ample space, adequate feeder railroads and good climate. In addition, it was convenient to the parent Company, and most important of all, a labor supply of sufficient volume and good calibre was close at hand.”

The book colorfully sets the scene for the yard’s beginning: “It was a cold, rainy Feb. 3, 1941, when ground was broken in the wind-swept flats, swampland and woods along the Cape Fear River for our great yard. So we began, with only a stretch of riverland, plans, a cadre of experienced men from Newport News, and orders from the President to do our part in providing a ‘bridge of ships.’”

The Ships

Wilmington was one of 10 shipyards that would build the Liberty cargo vessels. The Maritime Commission took a British design and adapted it for U.S. shipbuilding standards, and to meet the need to build as quickly and cheaply as possible.

The ships were 441.4 feet long and 56 feet wide, with a draft of 27 feet. Five cargo holds could carry 10,800 deadweight tons (the weight of cargo a ship can carry). A triple-expansion steam engine produced 2,500 horsepower and made 11 knots.

Most of the parts were prefabricated, transported to the shipyards, and riveted and welded on site.

They weren’t very attractive ships. Author John G. Bunker says Roosevelt described them as “a real ugly duckling” when reviewing plans for the vessel. But on Sept. 27, 1941, as the president christened the S.S. Patrick Henry, built in Baltimore, Maryland, he referenced Patrick Henry’s famous “give me liberty or give me death” speech. These ships, he said, would bring liberty to Europe. Thus, the name Liberty ship was coined.

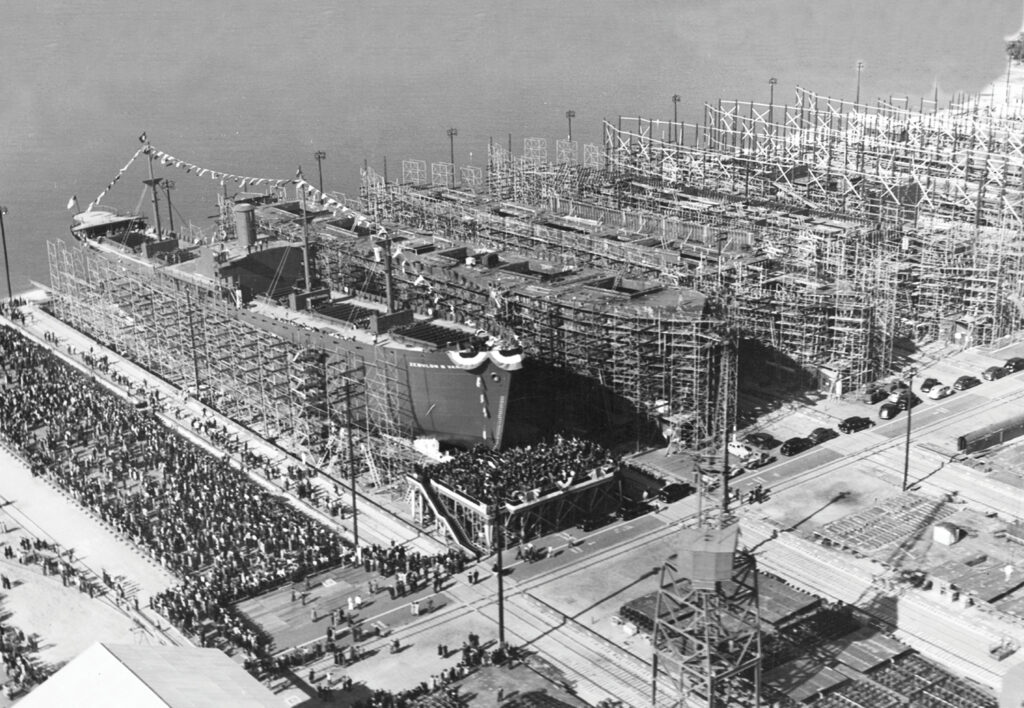

The NCSC’s first two keels were laid on May 22, 1941, just three and a half months after the Wilmington groundbreaking. The S.S. Zebulon B. Vance, named in honor of North Carolina’s Civil War-era governor, was launched into the Cape Fear River on Dec. 6, 1941 — hours before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that launched the United States into the war.

“An estimated 13,000 people were thrilled by the spectacle of the Zebulon B. Vance sliding gracefully into the Cape Fear River,” the Sunday Star-News reported.

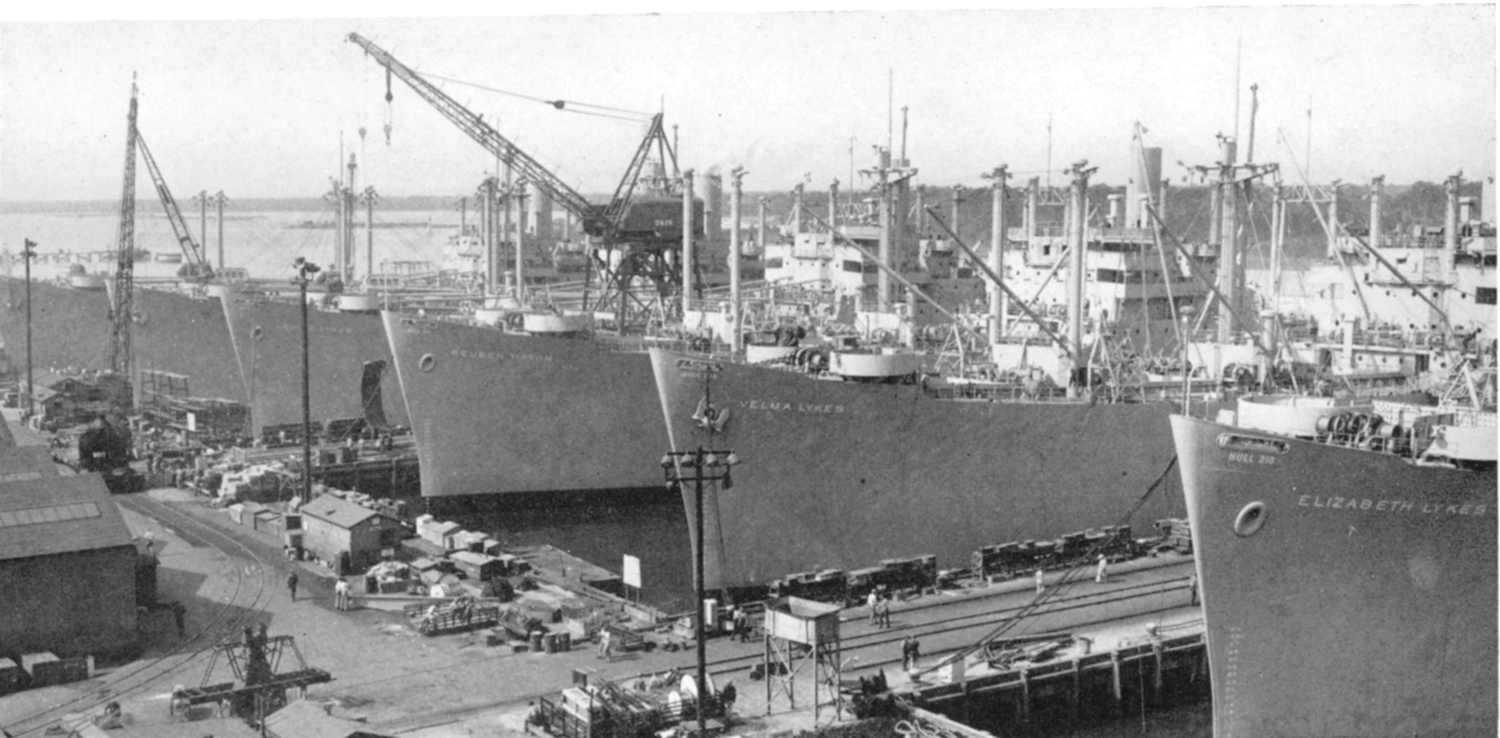

The Zebulon B. Vance was the first of the 126 Liberty ships built in Wilmington. The NCSC also produced 117 of the faster, larger C-2 boats, sometimes called Victory ships. As the war drew to a close, the C-2 boats were modified to become civilian cargo-passenger vessels. The yard’s final ship, the S.S. Santa Isabel, was made for the luxurious Grace Line.

The ships built in Wilmington served their country well. The Vance served as a freighter for most of the war, surviving a near-miss by a torpedo from a German U-boat and taking part in the North Africa invasion. She was converted into a hospital ship late in the war and renamed the S.S. John J. Meany, after a major and flight surgeon killed in the North African campaign. After the war, the ship was transferred to the Army Transportation Corps and used to convey British and other war brides to the United States, again as the Zebulon B. Vance.

The S.S. Virginia Dare, a Liberty ship delivered on March 27, 1942, came under heavy attack when delivering explosives to a port in Russia. Her crew shot down five aircraft.

The S.S. James Iredell earned a headline in the North Carolina Shipbuilder newspaper, published monthly for the workers at the shipyard. “SS Iredell’s Survival Of Fiery Voyage Proves We Build Good Ships,” proclaimed the March 1944 issue. Sailing in convoy for the Mediterranean with a “vital war cargo,” she was damaged when U-boats attacked and a ship ahead was “blown out of the water.” Iredell made it to Naples, where she was struck by three bombs.

“Whatever the enemy could deal out — submarine attack, direct bomb hits and fire — the S.S. James Iredell, our hull No. 45, could take it with the result that she is back in a home port preparing for another go at the Axis following one of the most trying voyages ever experienced by a Liberty ship,” the newspaper reported. “Her escape from destruction is regarded as additional proof of the sturdy design and construction of the ‘workhorses of the sea’ which are lifelines of our fighting forces overseas, the WSA (War Shipping Administration) report said.”

The Iredell later became one of four Liberty ships from Wilmington scuttled off the coast of France, part of a “motley fleet” of 89 ships sunk to form a breakwater for the critical Normandy invasion.

“Most of the ships had something wrong with them,” Joseph Israels II wrote in 1944 in the New York Tribune. “Some had gaping torpedo holes in their sides. The sterns of others were twisted by collisions or crippling mine explosions. But they steamed and chugged along with a mystifyingly heavy naval escort of planes and destroyers. … By the end of D-Day plus one, this fleet of merchant ghosts had successfully carried out one of the most difficult and dangerous operations on the Normandy beachhead. They had been sunk 1,000 yards off the hottest beaches, in shallow water. Their upper decks formed a steel breakwater, calmed the Channel chops and swells and allowed the thousands of smaller landing craft to hit the beaches safely with men and materials.”

The four Libertys sunk for D-Day were among the 28 Wilmington-built boats lost during the war. Enemy action sunk 23 Libertys, and one C-2 went down.

The People

The North Carolina Shipbuilding Company was justifiably proud of the quantity and quality of its ships. But the tale of the shipyard goes well beyond the vessels.

“More than anything else, it is the story of men and women — about 400 from Newport News, Virginia, and the thousands and thousands from throughout North Carolina and the South — who came here to do a job and did it well,” Roger Williams, president of the NCSC, wrote in the foreword to Five Years of North Carolina Shipbuilding.

Newport News Shipbuilding favored Wilmington because of “a good supply of intelligent, willing North Carolina men and women,” Williams wrote.

Intelligent and willing they may be, but most weren’t skilled. Workers from the parent company were sent to train new employees. Trade schools were established to teach drillers, reamers, welders, plumbers and steam engineers.

“Workers came from miles around, depleting farm labor as far out as Pender, Brunswick, Bladen, Duplin and Columbus Counties,” Jones wrote in his book A Sentimental Journey. “It helped solve any unemployment problems carried over from the Depression and paid well.”

Some commuted by bus and car. Others moved to Wilmington, pushing the population past 100,000. By October 1942, the NCSC was the state’s largest industry.

The area surrounding the shipyard, near Wilmington’s Sunset Park suburb, needed more housing. A trailer camp of 530 units was set up near the yard. New communities arose — Maffitt Village, Lake Forest, Hillcrest. Some 1,400 new homes were erected, many of them in Sunset Park.

The workers grew the economy. The shipyard employed 21,000 at its peak in 1943. Gross payroll that year was about $52.4 million. Most of that was spent locally.

Workers also went off to fight. Company records show approximately 6,800 employees entered the armed forces and merchant marine. At least 33 sacrificed their lives for the country.

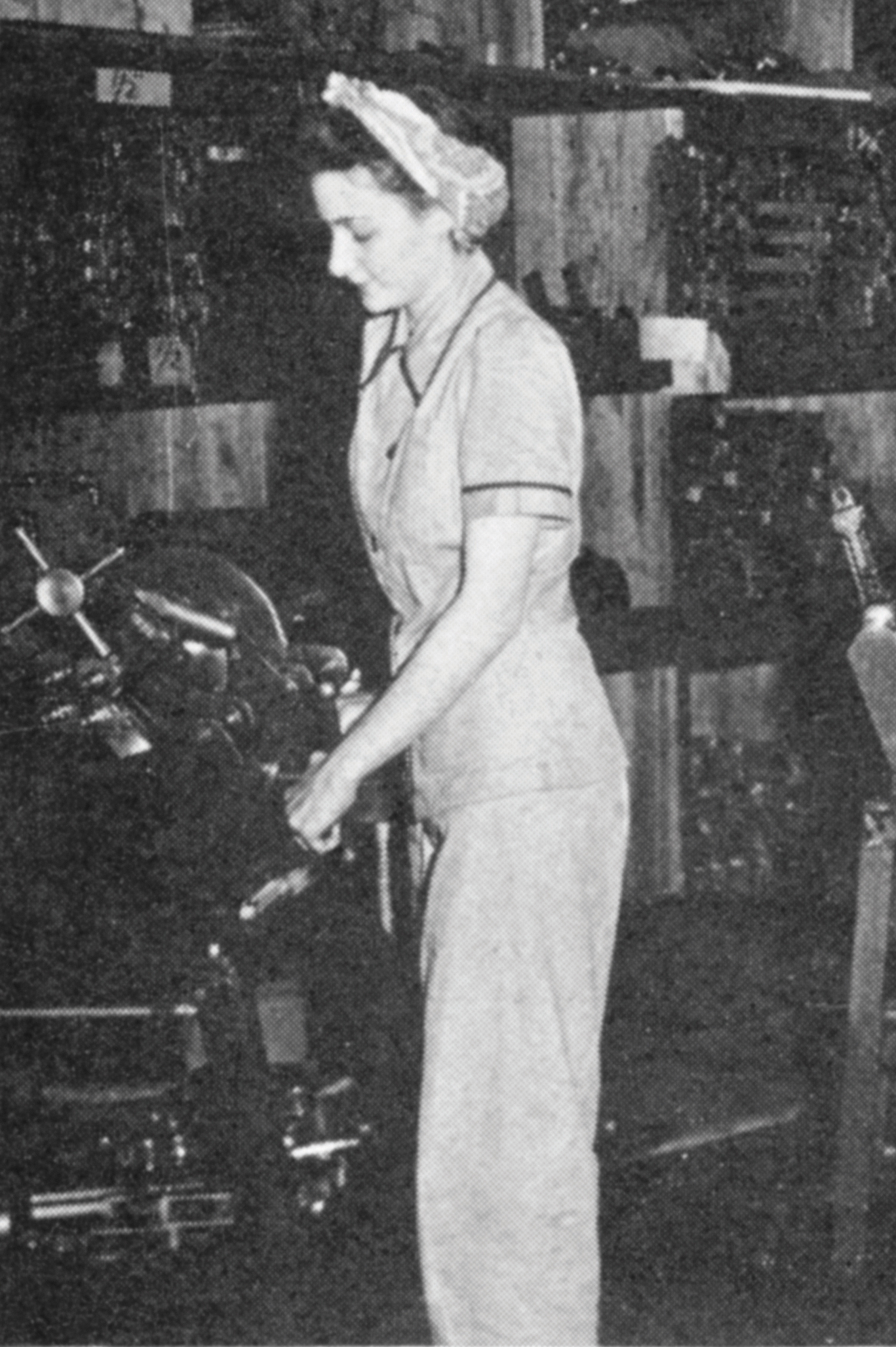

As men went off to war, women gained employment in nontraditional fields. More than 1,200 went into the production departments.

“About 20 percent of the employees were women,” Jones says. “We didn’t necessarily have Rosie the Riveter types; that was more associated with aircraft. But we did have women welders.”

In the days of segregation and Jim Crow laws, blacks and whites worked together. Some 30 percent of the shipyard workers were African-American, many employed in skilled positions.

Employees contributed more than labor to the war effort. They gave $239,009 in Community Chest campaigns, and $112,218 to Red Cross appeals. War bond purchases amounted to $20.4 million.

But most of all, they built ships. Quickly.

The Wilmington yard became noted for its speed. Average construction time from keel-laying to launch was honed down to 32 days by February 1943, third-best nationally.

Christmas was the only day off until mid-1944, when the yard closed Sundays during the July- August heat. Workers built ships 24 hours a day, with three shifts laboring around the clock. A blackout was in effect because of U-boats patrolling off the North Carolina coast, but it didn’t apply at the inland riverfront shipyard.

“The yard ran at night,” Scott says. “There was lots of light. It was more important to build boats at night than it was to have blackouts.”

Production didn’t slow after transitioning from Liberty to Victory ships. The February 1945 issue of the North Carolina Shipbuilder boasted the NCSC “led all other shipyards of the nation in production of ‘C’ merchant vessels last year by delivering 60 C-2s during the 12-month period.”

Admiral Emory Land, chairman of the U.S. Maritime Commission, took note.

“Their record speaks for itself,” he said. “They are tops.”

The end of the war heralded the end of the shipyard. The state legislature approved the State Port Authority in 1945, effectively transforming the World War II shipyard into a port facility.

But the legacy remains, aptly summed up by the editor of the North Carolina Shipbuilder in the newspaper’s final issue on June 1, 1946:

“They were farmers, factory workers, salesmen, clerks, truck drivers, housewives, clergymen, lawyers, actors, doctors, authors, artists, teachers, pupils, athletes, musicians, big businessmen, little businessmen, retired men, veterans, bankers, and others. They were different but had the same desire and they worked together with one aim — ‘To build good ships quickly!’ … The ships you have built will soon be as scattered as you, but their strength as units will last for ages because of the strength you put into them.”