You Have to Want It

Resilience and recovery: one warrior’s journey

BY Pat Bradford

It began with the desire to help others.

For many, the images of New York City firefighters rushing up flights of emergency stairwells in the burning World Trade Center towers on Sept. 11, 2001, are forever memories.

As a high schooler in Colorado Springs on that terrible day, Blake Reynolds’ 20-year trajectory would be set in motion. He was a 16-year-old junior driving to school with his younger sister, listening to the car radio.

Once there they watched the horror of the morning unfold. Plane impacts. Inferno. Horror. Death. Destruction. Images seared into retinas and minds.

As Reynolds processed what he saw and what he heard that day and in the weeks following, those heroic firefighters didn’t leave him. It would heavily impact his desire to serve as a firefighter or a military medic.

Fast forward to the summer of 2024. Reynolds is now 39, a top-tier military veteran, and a father of two. Reynolds and his wife of 16 years were birthing a local fitness business in Wilmington when the ground under him tilted.

The couple were in the process of bringing Deep End Fitness (DEF) training from Southern California to the East Coast. That’s deep end, as in the deep end of the pool. The concept was inspired by special forces combat diving and water survival programs.

DEF founders Prime Hall and Dom Tran are retired career Marine Corps Raiders and water survival instructors. Retired two years before Reynolds, they expanded their training into fitness in and under the water. The goal: to promote a shift in mental and physical health.

Hall and Tran also started an Underwater Torpedo League (UTL).

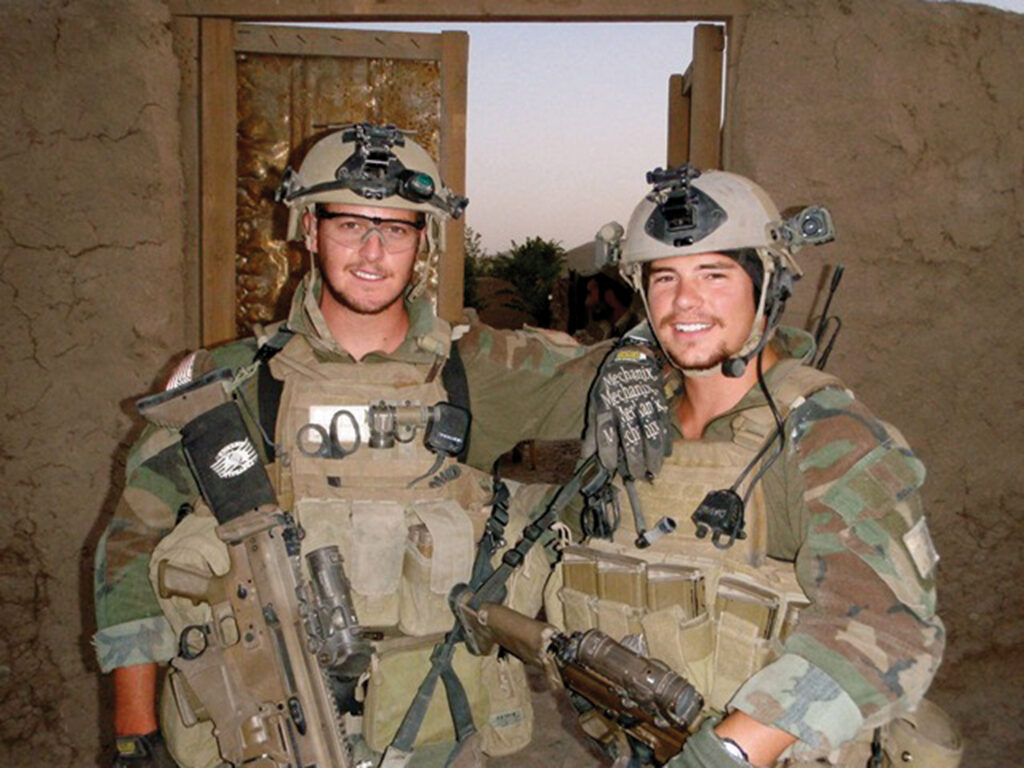

Reynolds is a retired career Special Operations Medic who served with Marine Recon, Marine Raiders and Naval Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU). He was a Navy Special Amphibious Reconnaissance Corpsman (SARC).

“To me being a SARC is a bizarre creature. It is very unknown; no one really understands what it is. A regular hospital corpsman is a medic in the Navy, an enlisted medic who operates on a ship, in a hospital, or a Marine Corps platoon,” Reynolds says. “SARCs take a massive step outside of that box.

“So, you are a medic. But to be a SARC, they send you to Force Recon Marine training. Force Recon used to be the top special ops for the Marine Corps. That transferred over to Marine Corps Special Operations, which became Marine Raiders — the USSOCOM entity [United States Special Operation Command], but since the GWOT [Global War On Terrorism] they are two separate units: Marine Raiders and Marine Force Recon. There’s a much bigger need for that now. It’s all guerrilla warfare. Unconventional tactics. You are fighting terrorists who hide in caves.”

A SARC must be as qualified as any other operator in a team.

“We are supposed to wear many conflicting hats. Medical provider and shooter. Team psychologist and team member. One day you are treating a 3-year-old Afghan child’s injury, the next you are assaulting through his father’s house and taking him to be processed,” says Reynolds.

SARCs must pass all the schools that are required to become a Recon Marine, combat diver, and military parachutist.

“They are also expected to build breaching charges and be able to shoot as well as any Recon or MARSOC operator. It’s a strange existence to take both parts of the job seriously. We look and act a lot like every other version of a special operator out there, but we’re the only ones that are classified as a medic first,” he says.

Reynolds misses it every day.

His first day as a civilian was June 28, 2018.

After transitioning out of the military, Reynolds continued in public service hired as a firefighter with the Wilmington Fire Department in January 2020. He also set about launching Deep End Fitness in Wilmington, with a desire to start an Underwater Torpedo League.

“This business is more than just working out,” Reynolds says. “It is a place where health and wellness are accessible through the unique benefits of aquatic fitness.”

He describes his mission as helping individuals, including fellow military veterans, first responders, and the broader community find strength, resilience, and balance.

Deep End Fitness Cape Fear officially launched on June 15, 2024, at the Earl Jackson Pool in downtown Wilmington.

Tragedy Strikes

Within weeks of the launch, members of Reynolds’s elite military circles began dying. All were Special Operations forces — SEALs, Marine Operators, EOD, and SARCs with parallel careers. Six died in July 2024.

EOD is the acronym for Explosive Ordinance Disposal.

“One close, five not best friends but still in my circles. I think we lost one a week all through July,” he says sitting at his kitchen counter in Wilmington as his daughters play in the next room. His wife stands at the counter by his side; his service dog, Heart, is at his feet.

He lists the men by name. Five were mental health-related. Four died by suicide; two listed as organ failure. Two were SARCs.

“There are under 300 of us in the entire Navy. Which is mind boggling.” Reynolds says.

He attended one funeral.

“Another SARC, a medic, he retired inside of two years ago but was still doing the job. Not for the military; private security, carrying a gun and a med bag,” he says.

The service was packed.

“It was devastating. He knew all I had gone through. I know what he went through. All of us had spent our entire career together at war,” says Reynolds. “That was a huge shock. He was a really fun guy. Kind. Why is it he took his life, and I didn’t? Because I was there, right there. What happened that was different with him? That’s what goes through all of our minds, am I next? That’s what guys are thinking.”

All were retired special operators but most were still working, contracting with the State Department or privately.

“Pretty much the whole mental health stigma is gone. The guys are all crying in the open,” Reynolds says.

Two more in his circle have died by suicide since this interview.

This kind of tragedy triggers the trauma in military members who did the impossible — deeds that were courageous, heroic, valiant and repeatedly unimaginable.

“We all need help,” he says.

This plays hard against what Reynolds calls “the ethos of military special operations,” and what he says is repeated continually in training.

“Suck it up. Suffer in silence. Take it like a man. That carries with you beyond the military. You were trained to suffer in silence. Don’t talk about it, don’t ask for help,” Reynolds says. “That’s a huge part.”

Operator Syndrome

He describes himself as having been lost.

“When I met Blake back in March of 2018, he was very guarded towards me. But I could tell he was very open to the idea of therapy given his prior positive experience in therapy,” says Reynolds’s counselor, Dr. Christopher Ostrander.

Reynolds gave Ostrander permission to discuss his diagnosis and treatments.

“Special Operations Forces (SOF) personnel typically face a four-tiered obstacle when leaving the service. Some are lucky to navigate one or two before leaving the service. Individuals like Blake face all four (biological, psychological, social, spiritual) all at once.”

Reynolds’ explanation is more visceral.

“I didn’t have an answer, I just want my friends to stop killing themselves,” he says. “Why are my brothers suddenly killing themselves?”

The post-nominals following Ostrander’s name identify his academic degrees and clinical counseling certifications: Ph.D., LCMHC, LMHC, LPC, and NCC. He is also the founder of Orchard Knob Counseling and the SOF Network, a nonprofit network of licensed mental health care providers focused on serving the special forces community nationally.

Ostrander referenced a 2020 article in the International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine titled “Operator syndrome: A unique constellation of medical and behavioral health-care needs of military special operation forces,” by B. Christopher Frueh, Alok Madan, J. Christopher Fowler, Sasha Stomberg, Major Bradshaw, Karen Kelly, Benjamin Weinstein, Morgan Luttrell, Summer G. Danner, and Deborah C. Beidel.

Their research identified a pattern from which they created an identifier.

“[There is] a consistent pattern of health-care difficulties within the special operation forces community that we and other special operation forces healthcare providers have termed Operator Syndrome,” he says.

From their research they list a litany of symptoms encompassed by the new diagnostic terminology.

“Interrelated health and functional impairments including traumatic brain injury effects; endocrine dysfunction; sleep disturbance; obstructive sleep apnea; chronic joint/back pain, orthopedic problems, and headaches; substance abuse; depression and suicide; anger; worry, rumination, and stress reactivity; marital, family, and community dysfunction; problems with sexual health and intimacy; being ‘on guard’ or hyper-vigilant; memory, concentration, and cognitive impairments; vestibular and vision impairments; challenges of the transition from military to civilian life; and common existential issues,” it states.

Multifaceted medical and behavioral healthcare needs were identified, which predictably, mirrors Reynolds’ career history.

“… mentally, emotional, and physically demanding service includes intensive operational training and combat deployment cycles. It is not unusual for an operator with 10 years or more of service to have up to 15 combat deployments and hundreds of individual direct-action missions. The nature of service includes years away from spouses and family; physical danger; death of friends and comrades in training and combat; combat and training injuries, acute and chronic, including both concussive impact injuries and blast-wave exposure that cause traumatic brain injuries; and existential and psychological damage.”

Retirement brings its own set of health problems.

“There is now a wave of retirements from the SOF community including many who have spent their entire adult lives in conflict or harm’s way and in a constant state of readiness for immediate deployment. Although they have many strengths, including high intelligence and extraordinary physical and mental toughness, many SOF operators now face a cascade of medical, emotional, and social problems that are not adequately captured by psychiatric diagnoses of depression or PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] as they transition to civilian life,” Ostrander says.

There are also typically physical symptoms.

“They face physical deterioration of joints, back issues from jumps, headaches due to TBI [traumatic brain injury], visual impairments, endocrine system dysfunction, sleep apnea, pain from old injuries,” he says.

Then there are the addictions.

“Just about every special operator that gets out is hooked on pills and booze,” Reynolds says. “All my surgeries in the military, pills were a part of it. But I would go back to my booze.”

The medications are free and flow freely.

“They just want to keep you going as long as possible. They spent hundreds of millions of dollars to train each guy, especially the guys in Tier 1 units. We are these awesome killing machines; they say just take these pills to kill that pain. It’s about keeping us in the fight, and we want that, too. At many units, high and low, at least half of them at some point have a stack of psych meds in their kits,” he says.

Ostrander clinically outlines the challenges of an SOF operator.

“Psychologically they face trauma from service but often find themselves ready to face childhood trauma that has finally surfaced. Anxiety, depression, hypervigilance, anger, grief, moral wounds or moral injury is a key factor here, too,” he says.

The mutual respect between Reynolds and Ostrander is evident.

“We got lucky and found a super solid marriage counselor. He started with us, but he ended up with just me. We found out about him from another veteran down the street,” Reynolds says.

Other than a shattered left thumb from a fall and shredded knees, Reynolds had no obvious injuries. But there were uncountable numbers of TBIs.

“We all have ’em, brain scans will show them,” he says.

His concussive impact injuries include motorcycle and dirt bike and ATV spills and crashes (dirt bikes are used to get through the mountains in Afghanistan). Parachuting. Amphibious operations. Boat drops out of a helicopter. Hard helicopter landings.

Then there’s blast-wave exposure from different munitions. Every shot, rocket or mortar fire, and breaching charge reverberates through the skull. This includes sitting next to a 50-caliber machine gun or spotting for 50-caliber sniper fire.

“Every time I go to the VA they ask, ‘Are you in pain today?’ Yes, I say. ‘From 1 to 10 how would you describe the pain level?’ they ask. The pain that I am in goes from the base of my skull to my tailbone, every single joint. My whole back hurts, both wrists, shoulders, hips, knees. A 5-7, some days a 10,” he says.

He’s had surgery for meniscus tearing, twice each knee.

There is heavy survival guilt. Not only living, but the guilt from never being shot or some sort of massive injury.

“I don’t know how I didn’t get a bullet, or take a big piece of shrapnel,” he says. “I kept all my limbs. I don’t know how, ’cause there were times when I have literally heard the crack of the round flying past my ear, hair blowing … I’d look behind me and see the wall completely all shot up.”

He also experiences the guilt of not keeping tabs on others like him who were in trouble.

Freedom Isn’t Free

Each of Reynolds’s deployments was different.

“For the job that I chose I pursued the hardest things, the most challenging things I could, and I did them all,” he says.

Four of his six deployments involved combat.

The first came with MARSOC in the fall of 2009 after about six years of training and two noncombat deployments.

Reynolds met his wife while stationed at Fort Bragg, during 18 Delta Special Operations Combat Medic training. They married while he was on leave from his second tour, forward deployed to Okinawa, Japan, with 3rd Recon.

After two deployments with MARSOC, his third operational assignment came just as his wife became pregnant. At this nine-year juncture, he considered getting out. Then came an opportunity to serve with a Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) unit. He was at a crossroads: get out, be an instructor, or go to a new unit.

The new unit took the family to Virginia Beach. Starting in 2013 at DEVGRU, he went through two full workup and deployment cycles to the Mideast. Between them, his second daughter was born.

“On 15 Feb. 2014, I got news that one of my best friends and significant mentor was KIA in Afghanistan,” he says.

It pushed him over the edge, moving into a much deeper and darker place. He began to unravel. There had been dozens of other friends lost, but this was different. He knew he was in trouble but wouldn’t admit it.

During 2016, he was pulled from the operational cycle and assigned to help in training. He had knee surgery and time to work on his mental health. The year was full of different treatments and diagnostics.

“I convinced the command in March 2017 to let me deploy again,” he says. “It was short-lived and I did not do well.”

Hitting rock bottom came with physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual injuries. The command surgeon sent him before a medical evaluation board.

During an earlier deployment, part of the job he provided was medical assistance to the people of the valley who brought their children to him. This is not the place to tell that diabolic story, but to attempt to convey Reynolds’ emotional distress in just describing seven months treating the native population’s child abuse. He uses just seven words: “33 under 3 with 3rd-degree burns.”

Those months became a trigger for him at home when he would hear the innocent shrieks and screams of his children playing.

Coping Measures

Reynolds was drinking daily.

“As I was circling the drain before I got out, we had talked about service dogs, because I love dogs,” he says.

But he resisted.

“I didn’t want to do that, be one of those veterans, a combat veteran walking around with a dog,” he says.

His wife made it happen.

“We had just moved. He was in a bad place, and we were looking at all options. I came across paws4people,” she says. “I called. They made it happen very, very quickly.”

Heart is a compact, loving Labrador retriever, adept at distractions.

“At first, she was always up in my face. She distracted by hopping up onto my lap, licking, snorting and spitting,” Reynolds says.

She is continually by his side.

“His military and combat experiences have taken a significant toll on him and his family,” paws4people says about the placement. “[Heart helps] by anchoring him when he is anxious, interrupting his nightmares, and paying attention — as Blake is often hypervigilant.”

Another trigger at home was perfection.

“At these commands you’re 100 percent invested. The level of the unit that I was at, there was zero tolerance for nonsense. [My children] are just little kids, full of life, little tiny people. They just didn’t know anything about the culture of perfection that was all triggering me. They are kids, she’s a wife, not Tier 1 operators on a no-fail mission,” he says.

He never failed out of school or training. He never quit something, content serving what he calls “the masters for SOF — all the people in suits that tell us what to do. All the people in uniforms with large silver stars on their collar.”

But it became more about serving the guys to his left and right.

“Our wives joke around about how our real marriage is to the military and our unit and they are just the side girl. There is some truth to that, because you definitely start to fall in love with what you are doing and the guys around you,” he says. “You will literally go and die for that guy. That’s how tight those bonds are.”

His substance abuse and grief seemed insurmountable stumbling blocks.

“When I met Blake, his body was banged up, he was grieving the loss of his career and the loss of so many friends along with many of the presenting issues I’ve described. In the early sessions I feared his grief was too great and his substance use was going to push him over the edge,” says Ostrander. “Additionally, how they leave the military is key as many get injured or med boarded out against their will. This loss can come with a heavy price. Substance use/abuse is usually at an elevated rate as this is part of the culture and an acceptable coping method. Adderall, antidepressants, and sleep meds can help get you through a rough patch, but they don’t address the root causes and are not a permanent solution.”

For Reynolds, marriage issues, family issues, and parenting struggles were real.

“During the last couple years of service, I started to see myself slip, take pills, drink gallons of coffee. My kids were the cutest little things — screams, loud voices would set me off. I was lying to myself about how serious it was,” Reynolds says.

Reynolds stashed his bottles in the garage, along with beer to mask the liquor smell.

Wake-Up Call

“There were significant obstacles that almost ended my marriage, my family, my career, and my life to put it bluntly. I served at the highest levels of military units and fell off my high horse in an extremely ugly way. It has been a long and hard journey back to living positively and healthy,” Reynolds says.

He had to make a choice.

“Basically, he got to the point, I told him he had to choose between his job or his family,” his wife says. “He needed to get out to save his life. He couldn’t have continued.”

It was an ultimatum he didn’t ignore.

“That caught my attention,” he says. “My wife said if you don’t X, you’re gonna get out of this house. I was like, oh, so I am going to be repeating what my father did. That was a huge scare, a huge wake-up call. I am doing the same stupid pattern of behavior that my dad did. And I refuse. I still love this woman. I need to stay with this woman. I have two adorable little girls. I am ending that right here.”

He was true to his word.

Ostrander identifies another key challenge.

“Socially, they face a complete culture shock and support elimination,” he says. “These guys are elite Formula One drivers with the best ‘pit crews’ in the world and then one day are left to learn everything on their own and do it alone. Since entering the military everything has been in a team and now there is no team. Additionally, and this falls under the psych section as well, the structure of the military and SOF is such a planned-out process and community that you can see how to go from E1 to E9 on a chart. They are told what uniforms to wear each day, and their language is truly a different dialect of English. All of it gone in a single day and they are launched into a new community, culture, language, role and even uniform.”

The Journey Back

Reynolds believes that sharing his journey, the list of treatments and therapies, can provide valuable insights and inspiration to others who are navigating their own paths to wellness and community service.

“I just want people to know there is hope,” he says.

When he was medically retired, he felt as if his purpose had been ripped away from him.

“Only when I look back on my whole military career am I happy with it. At first it felt like it was unfinished, I was robbed,” he says.

He no longer feels this.

“I am very proud of it, for the job I chose.”

One of the treatments he went through in 2017 was magnetic waves to stimulate specific areas of the brain. He did it to appease his leadership to get back on the field.

When he was sent to the Brain Treatment Center (BTC) in San Diego he connected with the clinic’s director, a retired Navy SEAL.

“He knows what I am going through. How do I stop this?” Reynolds says. “They did Magnetic Resonance Therapy (MERT) on me, and it really helps a lot of people with TBIs among many other things; depression, anxiety, and even autism,” Reynolds says.

He studied the techniques and tools that he could use to bring himself out of it. He describes yelling inside his head, bullying himself into good behavior by demeaning himself.

Pep talks went on for weeks, months and years: “Get your stuff together,” and “You can get through this.”

He doesn’t recommend it, but says it worked for him.

A good day meant exploring things that would bring positivity into his life.

He would get into his dress white uniform and have tea parties with his daughters. To them, he looked like a prince.

Service dogs like Heart are making a difference.

“I would always recommend if you’re going out of the military to get a service dog through paws4people,” Reynolds says.

Another was fake it ’til I make it.

Manifest the things that I do want. Trying to quit drinking, maybe drink a little less,” he says.

He offset his anger outbursts by using a little bit of cannabis.

“It would make me a much nicer person to be around at my house. Much happier. I did use that as a tool for a while, to bring down the booze bill, to lessen a worse thing that’s going on. It helped anger outbursts, being there for my family. I’d cut one of these gummies, and I’d be a much better person for the rest of the night. I’d sleep. It pushed me in a good direction,” he says.

“I spent my whole career missing dad stuff. I started trying, putting one foot in front of the other, trying not being a (expletive) father; one that was gone, always traveling. That took a while, to finally come down, to register that I don’t have to be this perfect soldier boy anymore. That’s a relief. Eventually the cloud starts to lift.”

In March 2019 he traveled to Mexico for what he deems a very effective treatment. Not federally approved or legal in this country, entheogen detox treatment is experimental.

“What I learned to admire about Blake early in our work was his ownership that it was his problem to solve. Though he seemed quite hopeless and headed toward a potential suicide attempt, he began bringing me novel solutions to his own drinking, and eventually the relatively unheard of treatment of entheogen,” says Ostrander. “Upon returning from an entheogen treatment, which was done under strict supervision of a highly qualified medical team, I could tell instantly how much hope and life was back in his eyes. His progress began to increase rapidly at this point. He was more involved with his wife and the kids and had kicked drinking overnight.”

He also received hormone replacement therapy.

“It’s a mix of TBI, depression, anxiety, and elevated cortisol and several other factors. It’s from years of no sleep and high stress. It makes our testosterone levels drop significantly when we hit our 30s and many guys end up on testosterone replacement therapy. It helps a lot of us significantly,” he says.

This was after he found the fire department, which filled many needs including the service and community he had been a part of for his whole adult life.

He was hired by the Wilmington Fire Department on Jan. 6, 2020, and attended Fire Academy during Covid.

“Part of his hopelessness I would say was in the idea his role or purpose as a SARC was lost and taken from him when he retired. As such, a man without a purpose and hope is not a man. What Blake has learned is that he still has the same purpose of serving his team/community. He just now does it in a different format,” says Ostrander.

Heart is in service with him as a Crisis Response Facility Dog, Rescue 2, A Shift.

Previously they were at Engine Company 8 for two years.

“For me to fully transition out, to be a fireman made sense,” says Reynolds. “I had to show up, shaved, to take care of my crew and the community. I still got the adrenaline rush. I got to go home to my family, and they get to come and visit me.”

Reynolds’s summary is that each person needs to go on a journey to find the combination of therapies and treatments that reconfigure their life to make for a totally new lifestyle.

“It’s never just one magic pill that the VA, or any doctor wants to prescribe,” he says.

He believes the starting point is with traditional counseling, then adding diet, breathwork, and exercise. That’s where Deep End Fitness and the Underwater Torpedo League come into the journey.

Finding the right nonprofits, doctors and friends is how to then discover more advanced ways.

“Coming back from suicidal ideation is possible. Coming out of bad mental health is possible. It does take effort and time, though. You have to want it and surround yourself with people that can help,” says Reynolds.

He believes finding a spiritual connection to a higher sense of purpose is an essential part of recovering. Reynolds’ desire is for others to know that, even though it can be overwhelming, you don’t have to do it alone, you can’t do it alone.

Terms (Military website descriptions)

• The Unites States Special Operation Command (USSOCOM or SOCOM) oversees the Special Operations Forces (SOF) of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force.

• The United States Marine Forces Special Operations Command

(MARSOC) is a component command of SOCOM that comprises the Marine Corps’ contribution to SOCOM. Marine Raiders deploy worldwide to accomplish complex special operations missions in uncertain environments with silent and strategic impact.

• Force Reconnaissance (FORECON) commonly Force Recon, are a part of United States Marine Corps that specialize in intelligence collection and direct action, often the first in the fight, with the capability of conducting clandestine missions in sensitive environments.

• Navy Special Amphibious Reconnaissance Corpsmen are known by the acronym SARC. As Special Operations Independent Duty Corpsman, they are given credentials as legitimate medical provides with a National Provider Identifier (NPI) number.

• In 1987, SEAL Team Six was dissolved. SEAL is an acronym for sea, air, and land, referring to the ability to operate in all conditions. The Naval Special Warfare Development Group was formed, essentially as SEAL Team Six’s successor.

• The Naval Special Warfare Development Group (NSWDG) is abbreviated as DEVGRU (Development Group) still commonly known as SEAL Team Six, the United States Navy component of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

• DEVGRU is administratively supported by Naval Special Warfare Command and operationally commanded by JSOC.

• Naval Special Warfare Command is the naval component of United States Special Operations Command, the unified command that oversees and conducts American special

operations and missions.

• DEVGRU conducts specialized missions including counterterrorism, hostage rescue, special reconnaissance, and direct action (short-duration strikes or small-scale offensive actions), often against high-value targets. Most information concerning DEVGRU is classified, and details of its activities are not usually commented on.

Through this article Blake continues to show the bravery and tenacity that characterized his military service and continues in his life after service.