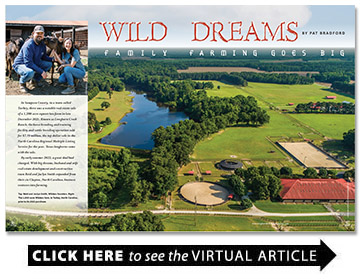

In Sampson County, in a town called Turkey, there was a notable real estate sale of a 1,200-acre equestrian farm in late December 2021. Known as Longhorn Creek Ranch, the horse breeding and training facility and cattle breeding operation sold for $7.19 million, the top dollar sale in the North Carolina Regional Multiple Listing Service for the year. Texas longhorns came with the sale.

By early summer 2022, a great deal had changed. With big dreams, husband and wife real estate development and construction team Reid and Jaclyn Smith expanded from their six Clayton, North Carolina, business ventures into farming.

Like many adjustments that occurred in the months that followed the viral outbreak of 2020, for Reid and Jaclyn Smith a new venture was birthed out of the pandemic.

During the shutdown, the couple and their children spent a lot of time on their 40-acre Clayton farm, buying their first Wagyu cows and diving into farming.

“We really leaned into it; as a family instead of watching TV and spending time on screens, we spent a lot of time outside. It grew our love for agriculture as a family,” Reid Smith says.

During this time in limbo a dream was also rekindled.

In the summer of 2019, Reid had seen an ad for a farm in Turkey, located just off I-40 in neighboring Sampson County, about a 45-minute drive south and west of their small-scale farm in Johnston County.

“It was beautiful, what a farm,” Reid says. “I thought it must be in Arizona or California, but in Turkey, N.C., what in the world? I looked it up and it was right off of 40 on the way to the beach.”

He messaged his friend Nick Phillips, founder and principal broker of Landmark Sotheby’s, to schedule a tour.

Despite being wowed, the timing was not right.

“It felt like pie in the sky; this will never happen,” Jaclyn says. “It’s so amazing, but we can’t do this.”

“Then the pandemic, and everything sort of went on hold, life kinda stopped,” says Reid.

In the spring of 2021, they again came across the 1,200-acre Sampson County farm with its fenced pastures and woods, a stocked 20-acre lake and other highly desirable improvements. It was still for sale, but the price had not moved.

“We were looking for a contiguous farm that could hold our big dreams,” Reid says. “The Sampson County farm had the contiguous acreage that we could put all that together to have our livestock, be able to grow our own food, for us and the livestock, and add the social aspect to it. It had everything in one place. And I kinda grew up in Wrightsville Beach, spending our summers down at Landfall. We have a house at Landfall, so it was uniquely in the path from here to there. It’s in a great location. The size of it, being able to have it all, it was really a perfect fit.”

Not wanting to seem too eager, they started the negotiations without retouring the property. After closing on Dec. 23, the couple wasted no time. They loaded up and moved their 100-plus cows down to Sampson the next day. They celebrated Christmas and the holiday break with the children on the farm in a travel trailer.

“We were that excited,” Reid says.

Reid grew up less than 30 minutes from Raleigh in Clayton in agriculture and says he really wanted to get back to it. His father raised Simmental cattle and still has a farm in western Johnston County where he raises SimAngus, a cross of Simmental and Angus cows.

Agriculture is North Carolina’s number one industry. The N.C. Chamber of Commerce reports agriculture and agribusinesses’ contribution to the state’s economy is $91.7 billion.

NC State University lists approximately 8 million acres of farmland in the state, with approximately 50,000 farms. But the number of farms is dwindling and many struggle to sustain a living. The state is losing agricultural land to development at a fast pace.

Farming is not a growing career choice any longer.

“It’s tough, because as we were running towards it, it seems like a lot of people are getting out of farming,” Reid says. “It’s just a generational thing. Jake, our farm director, gave us a stat, the average farmer’s age right now is 60-65. It’s a hard business, and that’s why there’s a unique appreciation for it.”

The couple share a love of golf. They met at Campbell University, each on the golf team, he a North Carolina farmer’s son, she born in New York, raised in Pennsylvania.

“Jaclyn’s a Yank,” he says.

Both are fiercely competitive.

“We do most things together; start our businesses together, play golf together, started our farm together,” says Reid.

Prior to starting their family, she was an elementary school teacher in the Johnston County school system. His degree was in business and accounting. He went to work with his dad building houses.

Jaclyn was licensed in real estate and in 2014 the couple started a home building and real estate company, building mostly apartments and houses. With the overflow of home buyers coming out of Raleigh, they were in the path of progress.

Spending most of their summers at the beach, they still compete and are past Couples Club champions at Landfall with a desire to retake their golf title this summer.

The children are fully immersed in the farm process and comfortable with raising livestock for food. They predict one animal-loving child will become a veterinarian.

“They have loved farming,” Jaclyn says. “There’s a love and appreciation for the animal while we get to love them. But then they still have a great appreciation that the animal doesn’t stay around forever, that it does produce dinner,” says Jaclyn.

They have a stewardship approach to their farm.

“We talk about it a lot, that we feel God has given us these animals to be good stewards over them, to take care of them, because their ultimate purpose is to take care of us,” Reid says.

A Rarity

Wagyu is, literally translated, Japanese cows. Described as beef with a rich creamy, buttery taste, and strict registration and DNA parentage testing, pure Wagyu is the most expensive beef. Its health benefits are touted, especially its good fats. The agricultural website agdaily.com lists Wagyu beef as having “50% more monounsaturated fat as commercial beef, and a fat profile comparable to salmon and olive oil with a lower cholesterol than chicken.”

The American Wagyu Association says “the monounsaturated to saturated fat ratio is higher in Wagyu than in other beef and the saturated fat contained in Wagyu is different. Forty percent is in a version called stearic acid, which is regarded as having a minimal impact in raising cholesterol levels. Wagyu beef is also higher in a type of fatty acid called conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Wagyu beef contain the highest amount of CLA per gram of any foodstuff – about 30 percent more than other beef breeds – due to higher linoleic acid levels. Foods that are naturally high in CLA have fewer negative health effects.”

Japanese Wagyu beef is said to be rich in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

Main Thing

The farm operation is rapidly growing with 270 Cornish Cross chickens, 28 Berkshire hogs, and two litters due in June, but beef is the main thing, including 158 Angus cows. The Wilders Wagyu herd currently numbers more than 300 head, with 34 calves born by mid-May this year, and another 70 expected.

“That’s the best beef out there,” says Reid.

The Wagyu cow was imported from Japan in 1976 before the government gave the breed a national treasure designation and banned exportation. It is said that less than 2,000 Wagyu were exported to the U.S.

“They only brought a handful over of full-blooded 100 percent registered Wagyu cattle. [Now] there’s between 15,000 and 20,000 domestically, that’s it. The Japanese view the Wagyu cows from the Kobe region as a national treasure. They take it as seriously as we take college football,” Reid says.

There is a crossbred American Wagyu, but it is not full-blooded Wagyu.

“We can trace all of our cows back to that [original] lineage. For each one of our registered cows, we know dating back four to five generations what their lineage is. We actually use that in our matings, as we are trying to improve our genetics,” says Reid.

At Wilders, genetics is a passion.

“What we’re trying to do with genetics is to continue to improve and balance the marbling with the size of the animals,” Reid says. The Wagyu cow genetically have a condition that allows them to marble. Most cows when they get to that age, they start to lose their marbling.”

Marbling impacts the beef’s flavor, texture, tenderness and juiciness.

Home Base

On West Main Street in downtown Clayton, a two-story, block deep brick building that once housed the North Carolina Paper Company, founded in 1919, is home to parent company RiverWild. Not much has changed on the outside but inside it is a modern office space for the couple’s businesses, complete with kitchen where gourmet lunches are created for employees from what is grown at Wilders.

“RiverWild has a lot of the executive leadership, investment and services for all of our other brands including Wilders and RiverWild. There are seven different companies that span the development, construction, and real estate process but then also a nonprofit,” says communications manager Hannah Smith (no relation).

These include Hearth Pointe Development doing land acquisition and entitlement; Jaclyn Smith Properties, the real estate arm; One27, handling residential construction; Providence Construction for land clearing, grading and site work; the agriculture Wilders; and a nonprofit.

What’s in a name?

“RiverWild, the Wild is our core values, how we do business,” Reid says.

Wild acts as an acronym: Will to win, Intentional adaptability, Live compassionately, and Disciplined execution.

“Wilders connects our core values with Wild. Wilders was also the township I grew up in. We live here in Johnston County and have started to raise a family. Just the concept of doing business with local farmers, we kinda like that name. We are trying to get new business as close to your local township as possible,” Reid says.

The couple started their nonprofit, One Compassion, when they started their businesses. It is focused on the community where they live, to serve those who are struggling and need a helping hand, including quality groceries for families.

Turkey, home to 427 on the 2020 census, was named in colonial times for the proliferation of wild turkeys in the area.

Once in Turkey, mere minutes from 1-40, visitors to the farm turn off the highway, drive across railroad tracks, between fields on both sides planted with row crops to feed the Wilders animals, including corn, soy and silage. Fifty acres of hay is planted.

Not all the property improvements, including the luxury 10-stall main horse barn and the 100-foot x 200-foot indoor arena, are in use yet. But the veterinary lab facilities are, as are the acres of fenced pastures, woods, paddocks and pens, the haybarn and silo and the ancillary buildings. The Southwestern-themed 3,000 square foot residence over the barn has morphed into a comfy family place, as have the additional scattered accommodations for staff.

The farm is also used for education for RiverWild’s 155 employees. All are encouraged to spend time on the farm. They have been team building, planting and harvesting potatoes and cabbage, feeding the animals, and just hanging out on employee Farm Fridays.

“We’ve tried to open that up to employees to experience agriculture. A lot of our employees say that’s their only chance to be on a farm, to experience that,” Jaclyn says.

Attending festivals and farmers markets to sell their meat is ramping up, including a booth at the Monday Wrightsville Beach Farmers Market.

All the cows, chickens and hogs are pasture raised, not housed. The cows are grass fed and grain finished. Reid says the intent is not to use any hormones or medicines, or even grain, except at the end for flavoring.

“Our goal, our message, is buy local, buy from your local farmer, understand what you’re buying whether it’s from us or Lewis Farms, wherever. Support your local farmer, buy from your local farmer,” Reid says.

They have an event scheduled for the farm in September for ranchers called Wilders Wagyu Field Day.

Still to come is an effort to engage the customer and create an agricultural experience through agritourism.

“Agritourism is something we are passionate about,” Jaclyn says.