Like checkers on a giant natural board, the coastal barrier islands constantly move played by the hands of storm, wind and tide. Created in ages past, the island chains have their own personalities and the water passages their nuances. Their contours shift at random. Shoals blossom overnight; oyster bars surface arbitrarily. A kicking onshore wind can blow an entire coastal bay dry in a few hours.

In these places of ceaseless change, the only constants are recurring, natural harmonies. The tides turn every six hours. From the depths of the ocean, the sun rises each morning. Polaris is always the North Star. At every season, birds, fish and animals arrive in a spectacular migration to the barrier sanctuaries. In the dune’s secret hollows, perpetual coastal storms form ephemeral freshwater ponds that feed shorebirds, songbirds, waterfowl, deer, butterflies and bees. These mysterious wonders do not cease.

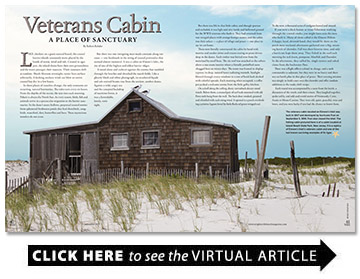

But there was one intriguing man-made constant along our coast — one landmark in the string of coastal peninsulas that seemed almost immortal. It was a cabin on Elmore’s Inlet, the site of one of the highest and oldest barrier ridges.

It stood alone and stalwart against the storms that rumbled through the beaches and thrashed the marsh fields. Like a ghostly black and white photograph, its weathered façade and salt-stained beams rose from the ancient, somber dunes. Against a wild, angry sea and the canopied backdrop of maritime forest, it was a formidable, lonely, eerie sight.

But there was life in that little cabin, and though spartan and secluded, it was light and airy inside and hallowed ground for the WWII veterans who built it. They had returned from war-ravaged places with strange foreign names, and the cabin was their solace — a place of refuge and peace — one place to say we are home.

These men literally constructed the cabin by hand with mortise and tendon joints and trusses resting on posts driven deep in the dunes. Each timber was ferried over from the mainland by small boat. The tin roof was attached to the rafters above a one-room interior where a friendly potbellied stove chugged heat on winter days. The room was framed in shiplap cypress; its deep, natural luster radiating warmth. Sunlight filtered through crusty windows to a row of bunk beds decked with colorful spreads. Each morning when occupied, a coffee pot perked a welcome aroma from the little galley kitchen.

On a shelf along the ceiling, dusty canvasback decoys stood watch. Below them, a crossed pair of surf rods mounted with old Penn reels hung from the wall. The back door creaked, groaned and whistled with each rising wind. It opened to a porch overlooking a pristine lagoon loved by little flocks of green-winged teal. To the west, a thousand acres of cordgrass bowed and swayed.

If you were a duck hunter or trout fisherman working through the coastal creeks, you might have seen the men who built it. Many of them called it the Elmore Hilton. A happy, loyal, devoted band, they would be there on the porch most weekend afternoons gathered over a big, steaming kettle of chowder. Fall was their favorite time, and only a hurricane kept them away. They fished in the surf each morning for red drum, pompano, bluefish and flounder. In the afternoons, they culled fat, single oysters and raked clams from the backwater flats.

There was a flight officer colonel in charge, and a tank commander as adjutant, but they were in no hurry and there was no battle plan in that place of peace. Their evening mission was simply to hold court over the chowder and offer random additions to the make-shift recipe.

Each round was accompanied by a taste from the kettle, a discussion of the result, and then a toast. They laughed together, spoke softly, and told and retold stories of Normandy, Crete, Anzio or Monte Cassino. They were old, quiet, peaceful, wise and brave, and you were lucky if you had the chance to know them.