Trash Nerds: Reclaiming Garbage from the Landfills and Oceans

BY Claudia Thompson

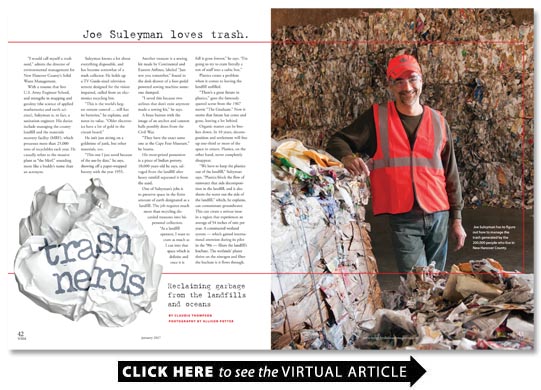

Joe Suleyman loves trash.

“I would call myself a trash nerd ” admits the director of environmental management for New Hanover County’s Solid Waste Management.

With a resume that lists U.S. Army Engineer School and strengths in mapping and geodesy (the science of applied mathematics and earth science) Suleyman is in fact a sanitation engineer. His duties include managing the county landfill and the materials recovery facility (MRF) which processes more than 25 000 tons of recyclables each year. He casually refers to the massive plant as “the Merf ” sounding more like a buddy’s name than an acronym.

Suleyman knows a lot about everything disposable and has become somewhat of a trash collector. He holds up a TV Guide-sized television remote designed for the vision impaired culled from an electronics recycling bin.

“This is the world’s largest remote control � still has its batteries ” he explains and notes its value. “Older electronics have a lot of gold in the circuit board.”

He isn’t just sitting on a goldmine of junk but other materials too.

“This one I just saved because of the use-by date ” he says showing off a paper-wrapped battery with the year 1955.

Another treasure is a sewing kit made by Continental and Eastern Airlines labeled “Just sew you remember ” found in the desk drawer of a foot-pedal powered sewing machine someone dumped.

“I saved this because two airlines that don’t exist anymore made a sewing kit ” he says.

A brass button with the image of an anchor and cannon balls possibly dates from the Civil War.

“They have the exact same one at the Cape Fear Museum ” he beams.

His most-prized possession is a piece of Indian pottery 10 000 years old he says salvaged from the landfill after heavy rainfall separated it from the sand.

One of Suleyman’s jobs is to preserve space in the finite amount of earth designated as a landfill. The job requires much more than recycling discarded treasures into his personal collection.

“As a landfill operator I want to cram as much as I can into that space which is definite and once it is full is gone forever ” he says. “I’m going to try to cram literally a ton of stuff into a cubic box.”

Plastics create a problem when it comes to leaving the landfill unfilled.

“There’s a great future in plastics ” goes the famously quoted scene from the 1967 movie “The Graduate.” Now it seems that future has come and gone leaving a lot behind.

Organic matter can be broken down. In 10 years decomposition and settlement will free up one-third or more of the space in return. Plastics on the other hand never completely disappear.

“We have to keep the plastics out of the landfill ” Suleyman says. “Plastics block the flow of rainwater that aids decomposition in the landfill and it also sheets the water out the side of the landfill ” which he explains can contaminate groundwater. This can create a serious issue in a region that experiences an average of 54 inches of rain per year. A constructed wetland system — which gained international attention during its pilot in the ’90s — filters the landfill’s leachate. The wetlands’ plants thrive on the nitrogen and filter the leachate is it flows through.

Every second 12.5 pounds of waste is created in New Hanover County. It’s a lot for Suleyman’s crew to keep up with — most of us never think about what happens to our garbage after we roll it to the curb.

“Most people quite frankly don’t care ” he says. “They leave for work and the recycling and trash cartons are full. When they come home from work they’re empty.”

The City of Wilmington picks up trash and recyclables for residents and private contractors provide those services for many county residents outside the city limits. The beach towns do their own thing; Wrightsville does not pick up recyclables but with the county maintains a recycle bin area near town hall.

There are eight of these recycling facilities for residents and businesses without curbside service including the one at Wrightsville Beach but that doesn’t guarantee everything makes it to the MRF. Or that everything that goes in the bins belongs there.

On a steamy Friday morning last summer the Moose Lodge off Carolina Beach Road near Monkey Junction was a recycling roundup. In just 45 minutes eight recyclers drove in parked unloaded their vehicles and drove out. Some dropped off only a few handfuls of plastic jugs or one box of presorted items. Others had full trunk loads of everything from bottles to ice cream cartons.

Mark Townsend a former University of North Carolina Wilmington environmental studies student makes recycling at the Moose Lodge location a practice.

“My apartment complex has no recycling service ” he says “so I am here to dispose of my plastic in a responsible way. I feel bad throwing it in the trash.”

Hearing this sentiment another recycler Amy Wagner walked over and high-fived him.

“I lived in a house that provided recycling but now they don’t so I bring it here ” she says. “I’m conditioned — I did it in the house I grew up in and now I just do it.”

Looking around at all the various items that comprise recyclables Wagner laments “I hate the plastic bags” while Townsend ponders “I wonder where the heck it all goes?”

As the two recycling enthusiasts chat Suleyman wearing a bright-orange vest with fluorescent yellow reflector blue jeans and work boots disappears head-first into a bin intended for cardboard.

“What is he doing?” Wagner asks.

He emerges from the hulking steel bin with a plastic bag full of lawn clippings shaking his head.

“Dumpers!” Townsend jests.

All business Suleyman doesn’t break stride. He drops the bag on the asphalt and disappears headfirst into another sorter. When he pops back out he is dragging a 10-foot piece of Styrofoam. This practice continues through each of the bins until Suleyman has filled the bed of his pickup truck bearing “LUVTRASH” on the license plate.

He points to the nonrecyclables including a mattress and sofa cushions.

“Someone is trying to avoid the $2 mattress recycling fee and a lot of times other contaminants end up in the bin by somebody who has the right intent but doesn’t know any better ” he says.

To Suleyman anything that violates the label on the giant navy blue container is a contaminant.

“Diapers. I have literally had someone tell me that because baby diapers are made of plastic and paper they have put them in the recycling bin � used ” Suleyman says.

On the molecular level there are also contaminants that leach from the trash into our soil water and air. This resonates with Richard Willis 73 another recycler.

“You don’t see them building landfills in the rivers or streams. We gotta keep that stuff out of the water ” he says.

Townsend agrees.

“I’ve heard about the plastic ocean ” he says referring to the accumulation of trash in the sea that has a deleterious effect on the food chain. He looks down as he adds “We’re slowly destroying the planet we rely on for natural resources.”

The science tends to support the claim that plastics and the environment just don’t mix. Dr. Pamela J. Seaton chair of the UNCW chemistry department and an organic chemist says her students are finding unusually high amounts of toxins resulting from the process of photodegradation which is one of only two processes that break down plastic.

Chemistry students are analyzing components of plastic trash to determine how these complex mixtures can be used to make fuel instead of clogging the oceans and landfills.

The theory of reclaiming plastic for the sole purpose of recycling it into petroleum is creating an intermarriage of disciplines at UNCW that could become a promising academic as well as environmental endeavor.

“From business students to political science to engineering and chemistry we are testing the feasibility of turning ocean plastic back into its original form: oil ” says Bonnie Monteleone founder and executive director of the nonprofit Plastic Ocean Project (POP) which is working with UNCW faculty and students. “We have got to find a way to give this stuff value because we don’t need to find it in our fish.”

An artist turned environmental trailblazer Monteleone has traveled four oceans collecting marine trash and turning it into a tool to educate people about the massive amounts of plastics — an estimated 8 million tons or 5.25 trillion pieces ofplastic — that end up in waterways globally.

“Our [country’s] stuff washes up in Europe ” says Monteleone who has done four years of research on micro-plastics which to the naked eye can look like sand or smaller broken down by crashing waves sun and salt. “There is so much garbage in Europe but we don’t find a lot of plastics washed up at Wrightsville Beach.”

But there are beachcombers who do find plastics regularly usually dumped by thoughtless beachgoers. Monique Brentlinger retired to Wrightsville Beach in 2013. She wanders uninhabited Masonboro Island as well as other shorelines collecting odds and ends for art mobiles.

“I try to recycle everything I find on the beach ” she says. “I always have a bag so anything I find I pick up.”

Along her morning strolls searching for material from whale sternums to lobster antennae she comes across a lot of inorganic material too.

“It’s more plastic bags bottle caps of course and cigarette butts ” she says. “That’s the stuff that tends to congregate along with the shells.”

Man-made chemical compounds added to petroleum to make plastic give the Earth a challenge. The compound that makes plastics lasts for up to 1 000 years.

But plastic trash could become a commodity based on new technology. If it came from oil the future of chemistry is proposing it can be returned to oil.

Salt Lake City company PK Clean provided UNCW with a tabletop reactor that can de-polymerize plastic by raising the temperature to 900 degrees which vaporizes it then cools it to a liquid. After extracting the manmade compounds initially applied to create plastic the end product is the original one: a golden honey-colored petroleum.

“And it’s a beautiful clean product ” Monteleone says. She says about 80 percent of reclaimed plastics that go through thispyrolysis process can become a resource.

Suleyman is keeping abreast of the science at UNCW and says it will happen.

“I have no doubt in my mind ” he says. “There are so many exciting technologies. No one wants to be the guinea pig and do it on a commercial scale.”

Armed with a subscription to the trash journal “Recycling Today “ Suleyman also keeps up with cutting-edge technology to deal with everything we throw out citing the science of anaerobic digestion on a farm as the harbinger for renewable energy.

“Just 10 years ago no one thought it could be done with anaerobic digestion — and now you have megawatt facilities turning cow manure into clean renewable energy ” he says.